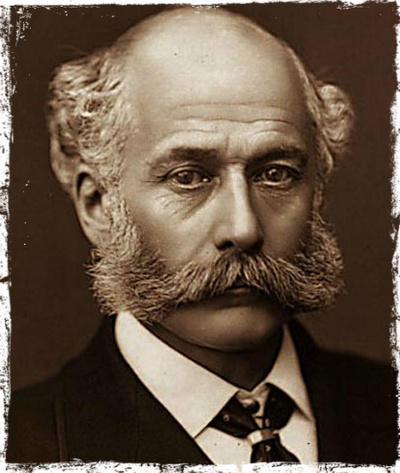

Sir Joseph William Bazalgette (Joseph Bazalgette)

Joseph William Bazalgette was born at Hill Lodge, Clay Hill, Enfield, London, the son of Joseph William Bazalgette (1783–1849), a retired Royal Navy captain, and Theresa Philo, née Pilton (1796–1850), and was the grandson of a French Protestant immigrant. He began his career working on railway projects, articled to noted engineer Sir John MacNeill and gaining sufficient experience (some in Ireland) in land drainage and reclamation works for him to set up his own London consulting practice in 1842. By the time he married in 1845, Bazalgette was deeply involved in the expansion of the railway network, working so hard that he suffered a nervous breakdown two years later.

While he was recovering, London’s short-lived Metropolitan Commission of Sewers ordered that all cesspits should be closed and that house drains should connect to sewers and empty into the Thames. As a result, a cholera epidemic (1848–49) killed 14,137 Londoners. Bazalgette was appointed assistant surveyor to the Commission in 1849, taking over as Engineer in 1852, after his predecessor died of “harassing fatigues and anxieties.” Soon after, another cholera epidemic struck, in 1853, killing 10,738. Medical opinion at the time held that cholera was caused by foul air: a so-called miasma. Physician Dr John Snow had earlier advanced a different explanation, which is now known to be correct: cholera was spread by contaminated water. His view was not then generally accepted.

Championed by fellow engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel, Bazalgette was appointed chief engineer of the Commission’s successor, the Metropolitan Board of Works, in 1856 (a post which he retained until the MBW was abolished and replaced by the London County Council in 1889). In 1858, the year of the Great Stink, Parliament passed an enabling act, in spite of the colossal expense of the project, and Bazalgette’s proposals to revolutionise London’s sewerage system began to be implemented. The expectation was that enclosed sewers would eliminate the stink (‘miasma’), and that this would then reduce the incidence of cholera.

At the time, the Thames was little more than an open sewer, devoid of any fish or other wildlife, and an obvious health hazard to Londoners. Bazalgette’s solution (similar to a proposal made by painter John Martin 25 years earlier) was to construct 82 miles (132 km) of underground brick main sewers to intercept sewage outflows, and 1,100 miles (1,800 km) of street sewers, to intercept the raw sewage which up until then flowed freely through the streets and thoroughfares of London. The outflows were diverted downstream where they were dumped, untreated, into the Thames. Extensive sewage treatment facilities were built in 1900. The scheme involved major pumping stations at Deptford (1864) and at Crossness (1865) on the Erith marshes, both on the south side of the Thames, and at Abbey Mills (in the River Lea valley, 1868) and on the Chelsea Embankment (close to Grosvenor Bridge; 1875), north of the river.The system was opened by Edward, Prince of Wales in 1865, although the whole project was not actually completed for another ten years.

Bazalgette’s foresight may be seen in the diameter of the sewers. When planning the network he took the densest population, gave every person the most generous allowance of sewage production and came up with a diameter of pipe needed. He then said ‘Well, we’re only going to do this once and there’s always the unforeseen’ and doubled the diameter to be used. His foresight allowed for the unforeseen increase in population density with the introduction of the tower block; with the original, smaller pipe diameter the sewer would have overflowed in the 1960s, rather than coping until the present day as it has.

The unintended consequence of the new sewer system was to eliminate cholera not only in places that no longer stank, but wherever water supplies ceased to be contaminated by sewage. The basic premise of this expensive project, that miasma spread cholera infection, was wrong; however, instead of this causing the project to fail, the new sewers succeeded in virtually eliminating the disease by removing the contamination.

Bazalgette’s capacity for hard work was remarkable; every connection to the sewerage system by the various Vestry Councils had to be checked and Bazalgette did this himself and the records contain thousands of linen tracings with handwritten comments in Indian ink on them “Approved JWB” “I do not like 6″ used here and 9″ should be used. JWB” and so on. It is perhaps not surprising that his health suffered as a result. The records are held by Thames Water in large blue binders gold-blocked reading “Metropolitan Board of Works” and then dated, usually two per year.

Bazalgette lived in 17 Hamilton Terrace, St John’s Wood, north London for some years. Before 1851, he moved to Morden, then in 1873 to Arthur Road, Wimbledon, where he died in 1891, and was buried in the nearby churchyard at St Mary’s Church.

Born

- March, 28, 1819

- Enfield, London

Died

- March, 15, 1891

- Wimbledon, London

Cemetery

- Wimbledon St Marys Churchyard

- Wimbledon, London