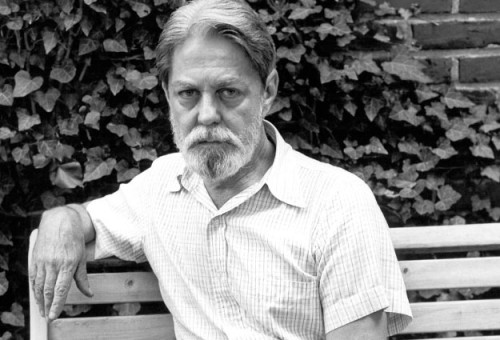

Shelby Foote (Shelby Dade Foote)

Foote was born in Greenville, Mississippi, the son of Shelby Dade Foote and his wife Lillian (née Rosenstock). Foote’s paternal grandfather, Huger Lee Foote (1854-1915), a planter, had gambled away most of his fortune and assets. His paternal great-grandfather, Hezekiah William Foote (1813-1899), was an American Confederate veteran, attorney, planter and state politician from Mississippi. His maternal grandfather was a Jewish immigrant from Vienna. Foote was raised in his father’s and maternal grandmother’s Episcopal faith. As his father advanced through the executive ranks of Armour and Company, the family lived in Greenville, Jackson, and Vicksburg, Mississippi, as well as Pensacola, Florida and Mobile, Alabama. Foote’s father died in Mobile when Foote was five years old; he and his mother moved back to Greenville. Foote was an only child, and his mother never remarried. When Foote was 15 years old, Walker Percy and his brothers LeRoy and Phinizy Percy moved to Greenville to live with their uncle — attorney, poet, and novelist William Alexander Percy — after the death of their parents. Foote began a lifelong fraternal and literary relationship with Walker; each had great influence on the other’s writing.

Foote edited The Pica, the student newspaper of Greenville High School, and frequently used the paper to lampoon the school’s principal. In 1935, Foote applied to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, hoping to join with the older Percy boys, but was denied admission because of an unfavorable recommendation from his high school principal. He presented himself for admission anyway, and as result of a battery of admissions tests, he was accepted. In 1936 he was initiated in the Alpha Delta chapter of the Alpha Tau Omega fraternity. Interested more in the process of learning than in earning an actual degree, Foote was not a model student. He often skipped class to explore the library, and once he even spent the night among the shelves. He also began contributing pieces of fiction to Carolina Magazine, UNC’s award-winning literary journal. Foote returned to Greenville in 1937, where he worked in construction and for a local newspaper, The Delta Democrat Times. Around this time, he began to work on his first novel.

In 1940 Foote joined the Mississippi National Guard and was commissioned as captain of artillery. After being transferred from one stateside base to another, his battalion was deployed to Northern Ireland in 1943. The following year, Foote was charged with falsifying a government document relating to the check-in of a motor pool vehicle he had borrowed to visit a girlfriend in Belfast Teresa Lavery— later his first wife — who lived two miles beyond the official military limits. He was court-martialed and dismissed from the Army. Shelby and Teresa divorced while she was living with his mother in New Orleans, after Shelby sent her to the US on a war ship convoy. Teresa later married Kermit Beahan the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Bombardier in Roswell, New Mexico after the end of the war. Foote came back to the United States and took a job with the Associated Press in New York City. In January 1945, he enlisted in the United States Marine Corps, but was discharged as a private in November 1945, never having seen combat. During his training with the Marines, he recalled a fellow Marine asking him “you used to be a[n] Army captain, didn’t you?” When Foote said yes, the fellow replied, “You ought to make a pretty good Marine private.” Foote returned to Greenville and took a job with a local radio station, but spent most of his time writing. He sent a section from his first novel to the Saturday Evening Post. “Flood Burial” was published in 1946, and when Foote received a $750 check from the Post as payment, he quit his job to write full-time.

Foote’s first novel, Tournament, was published in 1949. It was inspired by his planter grandfather, who had died two years before Foote’s birth. For his next novel, Follow Me Down, (1950) Foote drew heavily from the proceedings of a Greenville murder trial he attended in 1941 for both the plot and characters. Love in a Dry Season was his attempt to deal with the “so-called upper classes of the Mississippi Delta” around the time of the Great Depression. Foote often expressed great affection for this novel, which was published in 1951. In Shiloh (1952) Foote foreshadows his use of historical narrative as he tells the story of the bloodiest battle in American history to that point from the first-person perspective of seven different characters. Actually, the narrative is presented by 17 characters – Confederate soldiers Metcalf, Dade, and Polly; and Union soldiers Fountain, Flickner, with each of the twelve named soldiers in the Indiana squad given one section of that chapter. A close reading of this work reveals a very complete interlocked picture of the characters connecting with each other (Union with Union, Confederate with Confederate).

Jordan County: A Landscape in Narrative, was published in 1954 and is a collection of novellas, short stories, and sketches from Foote’s mythical Mississippi county. September, September (1978) is the story of three white Southerners who plot and kidnap the 8-year-old son of a wealthy African-American, told against the backdrop of Memphis in September, 1957. Although he was not one of America’s best-known fiction writers, Foote was admired by his peers—among them the aforementioned Walker Percy, Eudora Welty, and his literary hero William Faulkner, who once told a University of Virginia class that Foote “shows promise, if he’ll just stop trying to write Faulkner, and will write some Shelby Foote.” Foote’s fiction was recommended by both The New Yorker and critics from the New York Times book magazine.

Foote moved to Memphis in 1952. Upon completion of Jordan County: A Landscape in Narrative, he resumed work on what he thought would be his magnum opus, Two Gates to the City, an epic work he’d had in mind for years and in outline form since the spring of 1951. He had trouble making progress and felt he was plunging toward crisis with the “dark, horrible novel.” Unexpectedly, he received a letter from Bennett Cerf of Random House asking him to write a short history of the Civil War to appear for the conflict’s centennial. According to Foote, Cerf contacted him based on the factual accuracy and rich detail he found in Shiloh, but Walker Percy’s wife Bunt recalled that Walker had contacted Random House to approach Foote. Regardless, though Foote had no formal training as a historian, Cerf offered him a contract for a work of approximately 200,000 words. Foote worked for several weeks on an outline and decided that his plan couldn’t be done to Cerf’s specifications. He requested that the project be expanded to three volumes of 500,000 to 600,000 words each, and he estimated that the entire project would be done in nine years. Upon approval for the new plan, Foote commenced writing the comprehensive three volume, 3000-page history, together entitled The Civil War: A Narrative. The individual volumes are Fort Sumter to Perryville (1958), Fredericksburg to Meridian (1963), and Red River to Appomattox (1974).

Foote supported himself during the twenty years he worked on the narrative with Guggenheim Fellowships (1955–1957), Ford Foundation grants, and loans from Walker Percy. Foote labored to maintain his objectivity in the narrative despite his Southern upbringing. He deliberately avoided Lost Cause mythologizing in his work. He developed new respect for such disparate figures as Ulysses Grant, William T. Sherman, Patrick Cleburne, Edwin Stanton and Jefferson Davis. By contrast, he grew to dislike such figures as Phil Sheridan and Joe Johnston. He considered United States President Abraham Lincoln and Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest to be two authentic geniuses of the war. When he stated this opinion in conversation with one of General Forrest’s granddaughters, she replied after a pause, “You know, we never thought much of Mr. Lincoln in my family.” The work received generally favorable reviews, though scholars criticized Foote for not including footnotes and for neglecting subjects such as economics and politics of the Civil War era.

After finishing September, September, Foote resumed work on Two Gates to the City, the novel he had set aside in 1954 to write the Civil War trilogy. The work still gave him trouble and he set it aside once more, in the summer of 1978, to write “Echoes of Shiloh”, an article for National Geographic Magazine. By 1981, he had given up on Two Gates altogether, though he told interviewers for years afterward that he continued to work on it. In the late 1980s, Ken Burns had assembled a group of consultants to interview for his Civil War documentary. Foote was not in this initial group, though Burns had Foote’s trilogy on his reading list. A phone call from Robert Penn Warren prompted Burns to contact Foote. Burns and crew traveled to Memphis in 1986 to film an interview with Foote in the anteroom of his study. In November 1986, Foote figured prominently at a meeting of dozens of consultants gathered to critique Burns’ script. Burns interviewed Foote on-camera in Memphis and Vicksburg in 1987. In 1987, he became a charter member of the Fellowship of Southern Writers at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga.

When Burns’ documentary aired in September 1990, Foote appeared in almost ninety segments, about one hour of the eleven-hour series. Foote’s drawl, erudition, and quirk of speaking as if the war were still going on made him a favorite. He was described as “the toast of Public TV,” “the media’s newest darling,” and “prime time’s newest star,” and the result was a burst of book sales. In one week at the end of September 1990, each volume of the paperback The Civil War: A Narrative sold 1,000 copies per day. By the middle of 1991, Random House had sold 400,000 copies of the trilogy. Foote later told Burns, “Ken, you’ve made me a millionaire.” Foote’s substantive commentary in the Burns film dealt with a wide variety of battles, characters military and civilian, and issues. He also explained a puzzling question on nomenclature: why does the same battle often have two names? Foote’s answer: Northerners are usually from cities, so rivers and streams are noteworthy; whereas Southerners are usually rural, so they find towns noteworthy.

Foote professed to be a reluctant celebrity. When The Civil War was first broadcast, his telephone number was publicly listed and he received many phone calls from people who had seen him on television. Foote never unlisted his number, and the volume of calls increased each time the series re-aired. Many Memphis natives were known to pay Foote a visit at his East Parkway residence in Midtown Memphis. Horton Foote, the playwright and screenwriter (To Kill A Mockingbird, Baby the Rain Must Fall and Tender Mercies) was the voice of Jefferson Davis in the PBS series. The two Footes are third cousins; their great-grandfathers were brothers. “And while we didn’t grow up together, we have become friends; I was the voice of Jefferson Davis in that TV series,” Horton Foote added proudly.

In 1992, Foote received an honorary doctorate from the University of North Carolina. In the early 1990s, Foote was interviewed by journalist Tony Horwitz for the project on American memory of the Civil War which Horwitz eventually published as Confederates In The Attic (1998). Foote was also a member of The Modern Library’s editorial board for the re-launch of the series in the mid-1990s. (This series published two books excerpted from his Civil War narrative. Foote also contributed a long introduction to their edition of Stephen Crane’s The Red Badge of Courage giving a narrative biography of the author.) Foote was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 1994. Also in 1994, Foote joined Protect Historic America and was instrumental in opposing a Disney theme park near battlefield sites in Virginia. Along the way, Burns asked him to return for his upcoming documentary Baseball, where he appeared in both the 2nd Inning discussing his recollections of the dynamics of the crowds in his youth and in the 10th Inning (TV series), where he gave an account of his meeting Babe Ruth.

In one of his last television projects, Foote narrated the three-part series The 1840 Carolina Village, produced by award-winning PBS and Travel Channel producer C. Vincent Shortt in 1997. “Working with Shelby was a genuinely illuminating and humbling experience”, said Shortt. “He was the kind of academician who could weave a Civil War story into a discussion about fried green tomatoes — and do so without an ounce of presumption or arrogance. He was a treasure.” On September 2, 2001 Shelby Foote was the focus of the C-SPAN television program In-Depth. In a 3 hour interview, conducted by C-SPAN founder Brian Lamb, Foote shows off the library of his home, working room, writing desk and details the writing of his books as well as taking on-air calls. In 2003, Foote received the Peggy V. Helmerich Distinguished Author Award. The Helmerich Award is presented annually by the Tulsa Library Trust. Foote died at Baptist Hospital in Memphis on June 27, 2005, aged 88. He had had a heart attack after a recent pulmonary embolism.[9] He was interred in Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis. His grave is beside the family plot of General Forrest.

Born

- November, 17, 1916

- USA

- Greenville, Mississippi

Died

- June, 27, 2005

- USA

- Memphis, Tennessee

Cause of Death

- heart attack

Cemetery

- Elmwood Cemetery

- Memphis, Tennessee

- USA