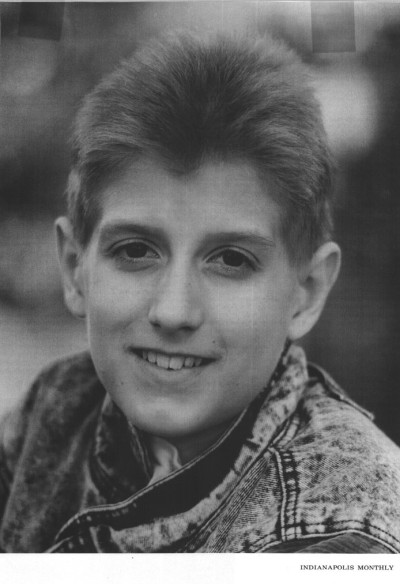

Ryan White (Ryan Wayne White)

Ryan White was born at St. Joseph Memorial Hospital in Kokomo, Indiana, to Jeanne Elaine Hale and Hubert Wayne White. He was circumcised and the bleeding would not stop. When he was three days old, doctors diagnosed him with severe hemophilia A, a hereditary blood coagulation disorder associated with the X chromosome, which causes even minor injuries to result in severe bleeding. For treatment, he received weekly transfusions of Factor VIII, a blood product created from pooled plasma of non-hemophiliacs, an increasingly common treatment for hemophiliacs at the time.

Healthy for most of his childhood, he became extremely ill with pneumonia in December 1984. On December 17, 1984, during a partial-lung removal procedure, White was diagnosed with AIDS. The scientific community knew little about AIDS at the time: scientists had only realized earlier that year that HTLV-III, now called HIV, was the cause of AIDS. White had apparently received a contaminated treatment of Factor VIII that was infected with HTLV-III, although exactly when he was infected remains unknown to this day. At that time, because the retrovirus that causes AIDS had been recently identified, much of the pooled factor VIII concentrate supply in hospitals was tainted because doctors did not know how to test for the disease, and donors often did not know they were infected or that blood was a factor in the transmission of the virus. Among hemophiliacs treated with blood-clotting factors between 1979 and 1984, nearly 90% became infected with HIV. At the time of his diagnosis, his T-cell count had dropped to 25 (a healthy individual without HIV will have around 500-1200). Doctors predicted White had only six months to live.

After the diagnosis, White was too ill to return to school, but by early 1985 he began to feel better. His mother asked if he could return to school, but was told by school officials that he could not. On June 30, 1985, a formal request to permit re-admittance to school was denied by Western School Corporation superintendent James O. Smith, sparking a legal battle that lasted for eight months. Western Middle School in Russiaville faced enormous pressure from many parents and faculty to ban White from the campus after his diagnosis became widely known. 117 parents (from a school of 360 total students) and 50 teachers signed a petition encouraging school leaders to ban White from school. Due to the widespread fear and ignorance of AIDS, the principal and later the school board succumbed to this pressure and banned White. The White family filed a lawsuit seeking to overturn the ban. The Whites initially filed suit in the U.S. District Court in Indianapolis. The court, however, declined to hear the case until administrative appeals had been resolved. On November 25, an Indiana Department of Education officer ruled that the school must follow the Indiana Board of Health guidelines and that White must be allowed to attend school.

The ways in which HIV spread were not fully understood in the 1980s. Scientists knew it spread via blood and was not transmittable by any sort of casual contact, but as recently as 1983, the American Medical Association had thought that “Evidence Suggests Household Contact May Transmit AIDS”, and the belief that the disease could easily spread persisted. Children with AIDS were still rare: at the time of White’s rejection from school, the Centers for Disease Control knew of only 148 cases of pediatric AIDS in the United States. Many families in Kokomo believed his presence posed an unacceptable risk. When White was permitted to return to school for one day in February 1986, 151 of 360 students stayed home. He also worked as a paperboy, and many of the people on his route canceled their subscriptions, believing that HIV could be transmitted through newsprint. The Indiana state health commissioner, Dr. Woodrow Myers, who had extensive experience treating AIDS patients in San Francisco, and the Centers for Disease Control both notified the board that White posed no risk to other students, but the school board and many parents ignored their statements. In February 1986, the New England Journal of Medicine published a study of 101 people who had spent three months living in close but non-sexual contact with people with AIDS. The study concluded that the risk of infection was “minimal to nonexistent,” even when contact included sharing toothbrushes, razors, clothing, combs and drinking glasses; sleeping in the same bed; and hugging and kissing.

When White was finally readmitted in April, a group of families withdrew their children and started an alternative school. Threats of violence and lawsuits persisted. According to White’s mother, people on the street would often yell, “we know you’re queer” at Ryan. The editors and publishers of the Kokomo Tribune, which supported White both editorially and financially, were also ridiculed by members of the community and threatened with death for their actions. Others felt such actions were both hypocritical and contradictory: those hostile implied that Ryan was likely a homosexual to have contracted HIV, but also maintained that HIV could be transmitted by casual contact. White attended Western Middle School for eighth grade for the entire 1986–87 school year, but was deeply unhappy and had few friends. The school required him to eat with disposable utensils, use separate bathrooms, and waived his requirement to enroll in a gym class. Threats continued. When a bullet was fired through the Whites’ living room window (no one was home at the time), the family decided to leave Kokomo. After finishing the school year, his family moved to Cicero, Indiana, where White enrolled at Hamilton Heights High School. On August 31, 1987, a “very nervous” White was greeted by school principal Tony Cook, school system superintendent Bob G. Carnal, and a handful of students who had been educated about AIDS and were unafraid to shake White’s hand.

The publicity of White’s trial catapulted him into the national spotlight, amidst a growing wave of AIDS coverage in the news media. Between 1985 and 1987, the number of news stories about AIDS in the American media doubled. While isolated in middle school, White appeared frequently on national television and in newspapers to discuss his tribulations with the disease. Eventually he became known as a poster child for the AIDS crisis, appearing in fundraising and educational campaigns for the syndrome. White participated in numerous public benefits for children with AIDS. Many celebrities appeared with White, starting during his trial and continuing for the rest of his life, to help publicly destigmatize socializing with people with AIDS. Singers John Cougar Mellencamp, Elton John and Michael Jackson, actor Matt Frewer, diver Greg Louganis, President Ronald Reagan and Nancy Reagan, Surgeon General Dr. C. Everett Koop, Indiana University basketball coach Bobby Knight and basketball player Kareem Abdul-Jabbar all befriended White. He also was a friend to many children with AIDS or other potentially debilitating conditions.

For the rest of his life he appeared frequently on Phil Donahue’s talk show. His celebrity crush, Alyssa Milano of the then-popular TV show Who’s the Boss?, met White and gave him a friendship bracelet and a kiss. Elton John loaned Jeanne White $16,500 to put toward a down payment on the Cicero home, and rather than accept repayment, placed the repaid money into a college fund for Ryan’s sister. In high school White drove a red Mustang convertible, a gift from Michael Jackson. Despite the fame and donations, White stated that he disliked the public spotlight, loathed remarks that seemingly blamed his mother or his upbringing for his illness, and emphasized that he would be willing at any moment to trade his fame for freedom from the disease. In 1988, White spoke before the President’s Commission on the HIV Epidemic. White told the commission of the discrimination he had faced when he first tried to return to school, but how education about the disease had made him welcome in the town of Cicero. White emphasized his differing experiences in Kokomo and Cicero as an example of the power and importance of AIDS education.

In 1989, ABC aired the television movie The Ryan White Story, starring Lukas Haas as Ryan, Judith Light as Jeanne and Nikki Cox as his sister Andrea. White had a small cameo appearance in the film, playing a boy also suffering from HIV who befriends Haas. Others in the film included Sarah Jessica Parker as a sympathetic nurse, George Dzundza as his doctor, and George C. Scott as White’s attorney, who legally argued against school board authorities. Nielsen estimated that the movie was seen by 15 million viewers. Some residents of Kokomo felt that the movie portrayed their entire town in an unfairly negative light. After the film aired, the office of Kokomo mayor Robert F. Sargent was flooded with complaints from across the country, although Sargent had not been elected to the office during the time of the controversy. By early 1990, White’s health was deteriorating rapidly. In his final public appearance, he hosted an after-Oscars party with former president Ronald Reagan and first lady Nancy Reagan in California. Although his health was deteriorating, White spoke to the Reagans about his date to the prom and his hopes of attending college.

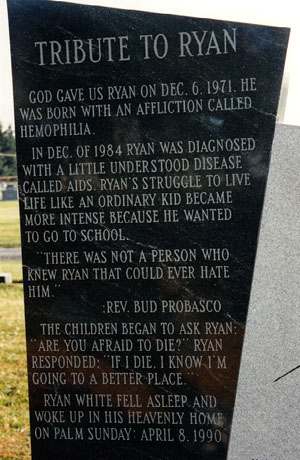

On March 29, 1990, White entered Riley Hospital for Children in Indianapolis with a respiratory infection. As his condition deteriorated, he was placed on a ventilator and sedated. He was visited by Elton John and the hospital was deluged with calls from well-wishers. White died on April 8, 1990. Over 1,500 people attended White’s funeral on April 11, a standing-room only event held at the Second Presbyterian Church on Meridian Street in Indianapolis. White’s pallbearers included Elton John, football star Howie Long and Phil Donahue. Elton John performed “Skyline Pigeon” at the funeral. The funeral was also attended by Michael Jackson and First Lady Barbara Bush. On the day of the funeral, former President Ronald Reagan wrote a tribute to White that appeared in The Washington Post. Reagan’s statement about AIDS and White’s funeral were seen as indicators of how greatly White had helped change perceptions of AIDS. White is buried in Cicero, close to the home of his mother. In the year following his death, his grave was vandalized on four occasions. As time passed, White’s grave became a shrine for his admirers.

Born

- December, 06, 1971

- USA

- Kokomo, Indiana

Died

- April, 08, 1990

- USA

- Indianapolis, Indiana

Cause of Death

- complications from AIDS

Cemetery

- Cicero Cemetery

- Cicero, Indiana

- USA