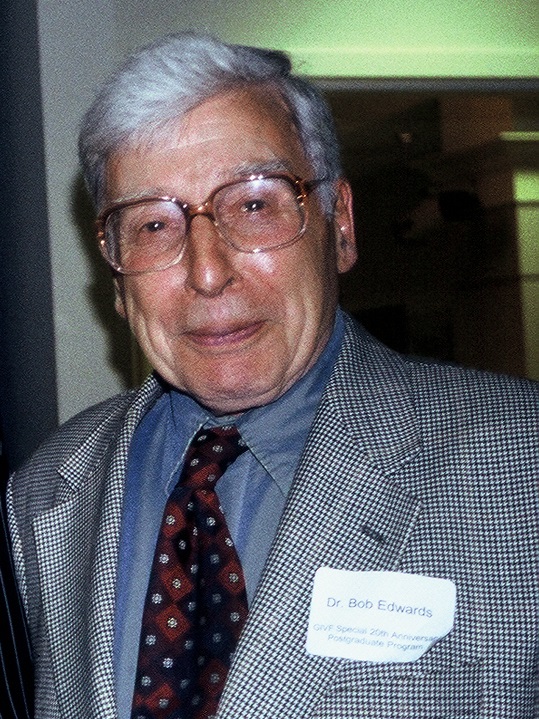

Robert G. Edwards (Robert G. Edwards)

Edwards was born in Batley, Yorkshire, and attended The Henry Box School in Witney. After finishing Manchester Central High School on Whitworth Street in central Manchester, he served in the British Army, and then completed his undergraduate studies in biology at the Bangor University. He studied at the Institute of Animal Genetics and Embryology at Edinburgh University, where he was awarded a PhD in 1955. After a year as a research fellow at the California Institute of Technology he joined the scientific staff of the National Institute for Medical Research at Mill Hill. After a further year at the University of Glasgow, in 1963 he moved to the University of Cambridge as Ford Foundation Research Fellow at the Department of Physiology, and a member of Churchill College, Cambridge. He was appointed Reader in physiology in 1969.

Circa 1960 Edwards started to study human fertilisation, and he continued his work at Cambridge, laying the groundwork for his later success. In 1968 he was able to achieve fertilisation of a human egg in the laboratory and started to collaborate with Patrick Steptoe, a gynecologic surgeon from Oldham. Edwards developed human culture media to allow the fertilisation and early embryo culture, while Steptoe utilized laparoscopy to recover ovocytes from patients with tubal infertility. Their attempts met significant hostility and opposition, including a refusal of the Medical Research Council to fund their research and a number of lawsuits. Additional historical information on this controversial era in the development of IVF has been published. The birth of Louise Brown, the world’s first ‘test-tube baby’, at 11:47 pm on 25 July 1978 at the Oldham General Hospital made medical history: in vitro fertilisation meant a new way to help infertile couples who formerly had no possibility of having a baby.

Refinements in technology have increased pregnancy rates and it is estimated that in 2010 about 4 million children have been born by IVF, with approximately 170,000 coming from donated oocyte and embryos. Their breakthrough laid the groundwork for further innovations such as intracytoplasmatic sperm injection ICSI, embryo biopsy (PGD), and stem cell research. Edwards and Steptoe founded the Bourn Hall Clinic as a place to advance their work and train new specialists. Steptoe died in 1988. Edwards continued on in his career as a scientist and an editor of medical journals.

Edwards died on 10 April 2013 after a long lung illness. A spokesperson for the University of Cambridge said “He will be greatly missed by family, friends and colleagues.” The Guardian reported that, as of Edwards’ death, more than four million births had resulted from IVF. Louise Brown said “His work, along with Patrick Steptoe, has brought happiness and joy to millions of people all over the world by enabling them to have children.” According to the BBC, his work was motivated by his belief that “the most important thing in life is having a child.” A plaque was unveiled at the Bourn Hall Clinic in July 2013 by Louise Brown and Alastair MacDonald – the world’s first IVF baby boy – commemorating Steptoe and Edwards.

Born

- September, 27, 1925

- Batley, England

Died

- April, 10, 2013

- England