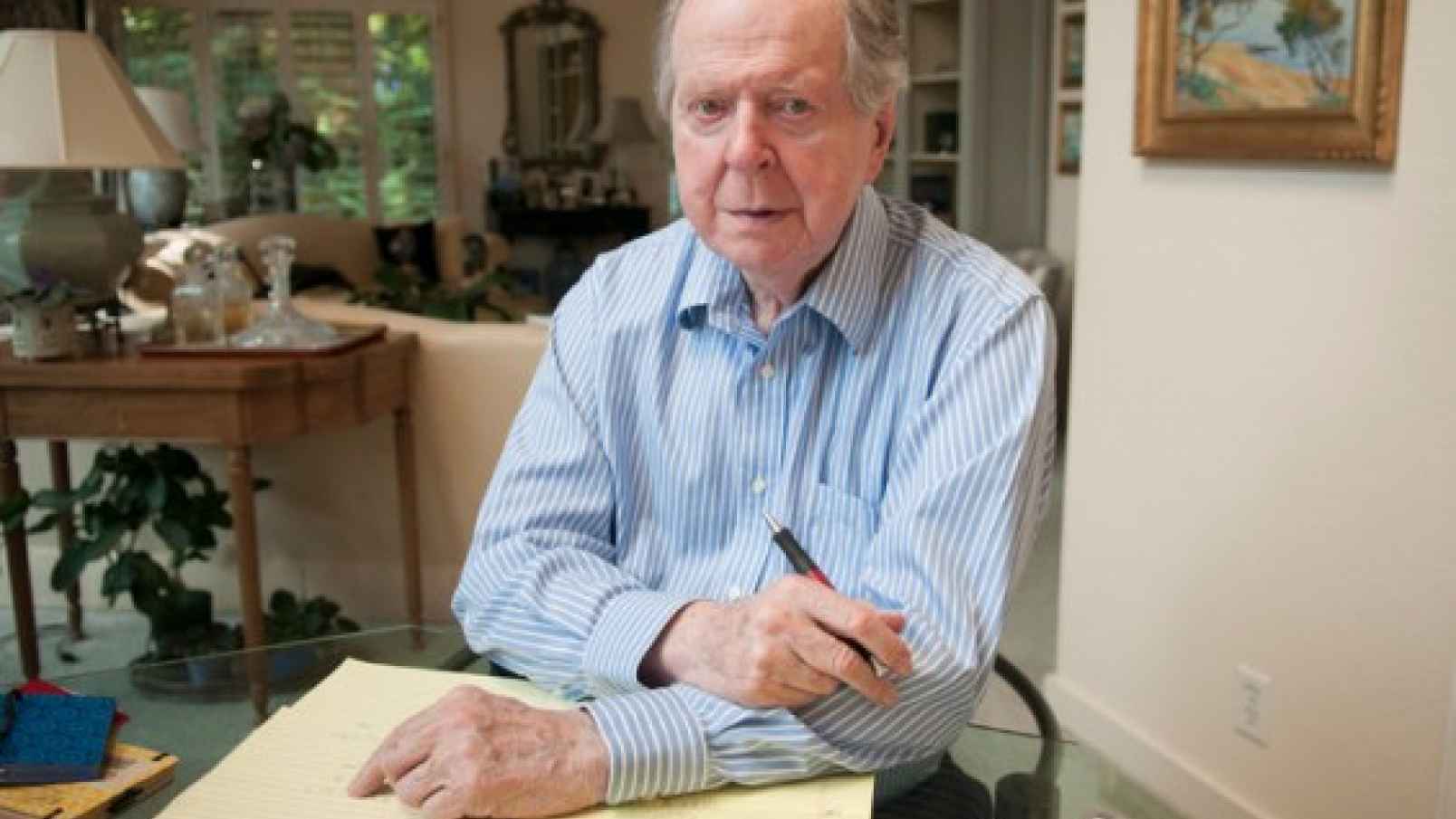

Robert Conquest (George Robert Acworth Conquest)

Conquest was born on 15 July 1917 in Great Malvern, Worcestershire, to an American father (Robert Folger Wescott Conquest) and an English mother (Rosamund Alys Acworth Conquest). His father served in an American Ambulance Service unit with the French Army in World War I, and was awarded the Croix de Guerre, with Silver Star in 1916. Conquest was educated at Winchester College, the University of Grenoble, and Magdalen College, Oxford, where he was an exhibitioner in modern history and took his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in Philosophy, Politics and Economics, and his doctorate in Soviet history. In 1937, after studying at the University of Grenoble, Conquest went up to Oxford, joining both the Carlton Club and, as an “open” member, the Communist Party of Great Britain. Fellow members included Denis Healey and Philip Toynbee. When World War II broke out, Conquest was commissioned into the Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry and served with the regiment from 1939 to 1946. In 1942, he married Joan Watkins, with whom he had two sons. In 1943, he was posted to the School of Slavonic and East European Studies to study Bulgarian, which is today part of University College London. In 1944, Conquest was posted to Bulgaria as a liaison officer to the Bulgarian forces fighting under Soviet command, attached to the Third Ukrainian Front, and then to the Allied Control Commission. There, he met Tatiana Mihailova, who later became his second wife. At the end of the war, he joined the Foreign Office, returning to the British Legation in Sofia. Witnessing first-hand the communist takeover in Bulgaria, he became completely disillusioned with communist ideas. He left Bulgaria in 1948, helping Tatiana escape the new regime. Back in London, he divorced his first wife and married Tatiana. In 1951, Tatiana Conquest was diagnosed with schizophrenia, and in 1962 the couple divorced.

Conquest joined the Foreign Office’s Information Research Department (IRD), a unit created by the Labour government to “collect and summarize reliable information about Soviet and communist misdoings, to disseminate it to friendly journalists, politicians, and trade unionists, and to support, financially and otherwise, anticommunist publications.” In 1950 he served briefly as First Secretary in the British Delegation to the United Nations. In 1956, Conquest left the IRD, later becoming a freelance writer and historian. During the 1960s, Conquest edited eight volumes of work produced by the IRD, published in London by the Bodley Head as the Soviet Studies Series; and in the United States republished as The Contemporary Soviet Union Series by Frederick Praeger, whose U.S. company published, in addition to works by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, Milovan Đilas, Howard Fast, and Charles Patrick Fitzgerald, a number of books on communism. In 1962–63, Conquest was literary editor of The Spectator, but resigned when he found it interfered with his historical writing. His first books on the Soviet Union were Common Sense About Russia (1960), The Soviet Deportation of Nationalities (1960) and Power and Policy in the USSR (1961). His other early works on the Soviet Union included Courage of Genius: The Pasternak Affair (1961) and Russia After Khrushchev (1965). In 1967, Conquest, along with Kingsley Amis, John Braine and several others signed a letter to The Times entitled “Backing for U.S. Policies in Vietnam”, supporting the US government in the Vietnam War.

In 1968, Conquest published what became his best-known work, The Great Terror: Stalin’s Purge of the Thirties, the first comprehensive research of the Great Purge, which took place in the Soviet Union between 1934 and 1939. The book was based mainly on information which had been made public, either officially or by individuals, during the so-called “Khrushchev Thaw” in the period 1956–64. It also drew on accounts by Russian and Ukrainian émigrés and exiles dating back to the 1930s, and on an analysis of official Soviet documents such as the Soviet census. The most important aspect of the book was that it widened the understanding of the purges beyond the previous narrow focus on the “Moscow trials” of disgraced Communist Party of the Soviet Union leaders such as Nikolai Bukharin and Grigory Zinoviev, who were executed after summary show trials. The question of why these leaders had pleaded guilty and confessed to various crimes at the trials had become a topic of discussion for a number of western writers, and had underlain books such as George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four and Arthur Koestler’s Darkness at Noon. Conquest argued that the trials and executions of these former Communist leaders were a minor detail of the purges. By his estimates, Stalinist famines and purges had led to the deaths of 20 million people. He later stated that the total number of deaths could “hardly be lower than some thirteen to fifteen million.”

Conquest sharply criticized Western intellectuals such as Beatrice and Sidney Webb, George Bernard Shaw, Jean-Paul Sartre, Walter Duranty, Sir Bernard Pares, Harold Laski, D. N. Pritt, Theodore Dreiser, Bertold Brecht and Romain Rolland for being dupes of Stalin and apologists for his regime, citing various comments they had made denying, excusing, or justifying various aspects of the purges. After the opening up of the Soviet archives in 1991, detailed information was released that Conquest argued supported his conclusions. When Conquest’s publisher asked him to expand and revise The Great Terror, Conquest is famously said to have suggested the new version of the book be titled I Told You So, You Fucking Fools. In fact, the mock title was jokingly proposed by Conquest’s old friend, Sir Kingsley Amis. The new version was published in 1990 as The Great Terror: A Reassessment. The revisionist historian J. Arch Getty disagreed, writing in 1994 that the archives did not support Conquest’s casualty figures. Although some aspects of his work continue to be disputed by those on the left, according to poet Czesław Miłosz he has been vindicated by history. In 2000, Michael Ignatieff wrote “One of the few unalloyed pleasures of old age is living long enough to see yourself vindicated. Robert Conquest is currently enjoying this pleasure.”

In 1964, he married Caroleen MacFarlane, but the marriage failed and he began dating Elizabeth Neece Wingate, a lecturer in English and the daughter of a United States Air Force colonel, in 1978. He and Wingate married the next year. In 1981, Conquest moved to California to take up a post as Senior Research Fellow and Scholar-Curator of the Russian and Commonwealth of Independent States Collection at Stanford University’s Hoover Institution, where he remained a Fellow. He has numerous grandchildren from his sons and stepdaughter. Conquest was a fellow of the Columbia University’s Russian Institute, and of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars; a distinguished visiting scholar at the Heritage Foundation; a research associate of Harvard University’s Ukrainian Research Institute. In 1990, Conquest was the presenter of Red Empire, a seven-part mini-series documentary on the Soviet Union produced by Yorkshire Television. Conquest died of pneumonia in Stanford, California, on 3 August 2015 at the age of 98.

Born

- July, 15, 1917

- United Kingdom

- Great Malvern, Worcestershire, England

Died

- August, 03, 2015

- USA

- Stanford, California

Cause of Death

- pneumonia