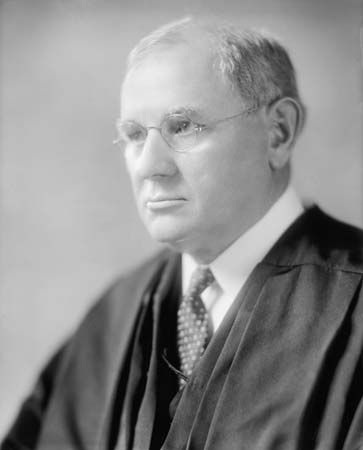

Pierce Butler (Pierce Butler)

Butler was born to Patrick and Mary Ann Butler, Catholic immigrants from County Wicklow, Ireland. (The pair met in Galena, Illinois, after having left the same part of Ireland because of the Irish Potato Famine.) Soon, the couple settled in Sciota, then Waterford, Dakota County, Minnesota. Their son Pierce Butler was the sixth of nine children born in a log cabin; all but his sister would live to adulthood. Butler graduated from Carleton College, where he was a member of Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity. He read for the law and was admitted to the bar in 1888. He married Annie M. Cronin in 1891.

He was elected as county attorney in Ramsey County in 1892, and re-elected in 1894. Butler joined the law firm of How & Eller in 1896, which became How & Butler after the death of Homer C. Eller the following year. He accepted an offer to practice in St. Paul, Minnesota, where he took care of railroad-related litigation for James J. Hill. He was highly successful in representing railroads.

In 1905 he returned to private practice and rejoined Jared How. He had also served as a lawyer for the company owned by his five brothers. In 1908, Butler was elected President of the Minnesota State Bar Association. From 1912 to 1922, he worked in railroad law in Canada, alternately representing the shareholders of railroad companies and the Canadian government; he produced favorable results for both. When he was nominated for the United States Supreme Court in 1922, Butler was in the process of winning approximately $12,000,000 for the Toronto Street Railway shareholders.

Although he was supported by Chief Justice and former President William Howard Taft, Butler’s opposition to “radical” and “disloyal” professors at the University of Minnesota (where he had served on the Board of Regents) made him a controversial Supreme Court nominee when proposed by Republican President Warren Harding. The Senator-elect Henrik Shipstead of his home state opposed him, as did the Progressive Senator Robert M. LaFollette, Sr. of Wisconsin. Also against his confirmation were labor activists, some liberal magazines (the New Republic and The Nation) and, on the other side, the Ku Klux Klan because he was Catholic. However, with the support of prominent Roman Catholics, fellow lawyers (the Minnesota State Bar Association strongly endorsed him), and business groups (especially railroad companies), as well as Minnesota’s other senator Knute Nelson, Butler was confirmed on Dec 21, 1922, by a wide margin of 61 to 8. The Senators who voted against him were five Democrats (Walter F. George, William J. Harris, J. Thomas Heflin, Morris Sheppard, and Park Trammell) and three Republicans (Robert M. LaFollette, Sr., Peter Norbeck, and George W. Norris). He took his seat on the Court on January 2, 1923.

As an Associate Justice, Butler vigorously opposed regulation of business and the implementation of welfare programs by the federal government (as unconstitutional). During the Great Depression, he ruled against the constitutionality of many “New Deal” laws— the Agricultural Adjustment Administration and the National Recovery Administration— which had been supported by his fellow Democrat Franklin Roosevelt. This earned him a place among the so-called “Four Horsemen,” which also included James Clark McReynolds, George Sutherland, and Willis Van Devanter. As a conservative commentator noted, Butler did not give up his seat willingly — other justices may have been forced out — but he had to be carried out of office. He wrote the majority opinion (6-3) in United States v. Schwimmer, in which the Hungarian immigrant’s application for citizenship was denied because of her candid refusal to take an oath to “take up arms” for her adopted country.

In Palko v. Connecticut, Butler was the lone dissenter on the court; the rest of the justices believed that a state was not restrained from trying a man a second time for the same crime. Butler believed this violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. He sided with the majority in Pierce v. Society of Sisters, holding unconstitutional an Oregon state law which prohibited parents from sending their children to private or religious schools.

In Buck v. Bell, Butler was the only Justice who dissented from Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr.’s opinion holding that the forced sterilization of an allegedly “feeble-minded” woman in Virginia was constitutional. Holmes believed that Butler’s religion influenced his thinking in Buck, remarking that “Butler knows this is good law, I wonder whether he will have the courage to vote with us in spite of his religion.” Although Butler dissented in both Buck and Palko, he did not write a dissenting opinion in either case; the practice of a Justice’s noting a dissent without opinion was much more common then than it would be in the later 20th and early 21st centuries. Another consequential dissent was from the opinion expressed in Olmstead v. United States which upheld federal wiretapping. He took an expansive view of 4th Amendment protections.

Butler died in Washington, DC, at the age of 73 while still on the court. He is buried in the Calvary Cemetery in St. Paul. Justice Butler was one of 13 Catholic justices – out of 112 total in the history of the Supreme Court. 40.5 cubic feet (1.15 m3) of his and his family’s collected papers are with the Minnesota Historical Society. Other papers are collected elsewhere. Pierce Butler Route in Saint Paul, Minnesota, is named in honor of Butler.

Born

- March, 17, 1866

- USA

- Dakota County, Minnesota

Died

- November, 16, 1939

- USA

- Washington D.C.

Cemetery

- Calvary Cemetery

- St. Paul, Minnesota

- USA