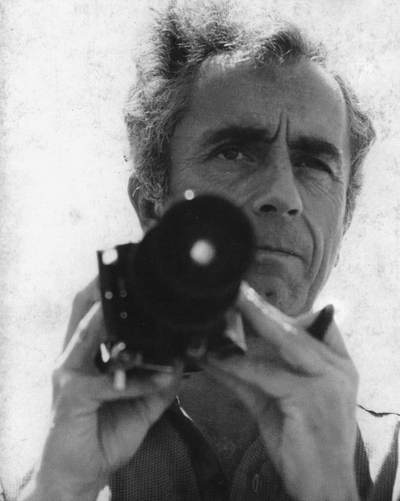

Michelangelo Antonioni (Michelangelo Antonioni)

Antonioni was born into a prosperous family of landowners in Ferrara, Emilia Romagna, in northern Italy. He was the son of Elisabetta (née Roncagli) and Ismaele Antonioni. The director explained to Italian film critic Aldo Tassone: My childhood was a happy one. My mother… was a warm and intelligent woman who had been a labourer in her youth. My father also was a good man. Born into a working-class family, he succeeded in obtaining a comfortable position through evening courses and hard work. My parents gave me free rein to do what I wanted: with my brother, we spent most of our time playing outside with friends. Curiously enough, our friends were invariably proletarian, and poor. The poor still existed at that time, you recognized them by their clothes. But even in the way they wore their clothes, there was a fantasy, a frankness that made me prefer them to boys of bourgeois families. I always had sympathy for young women of working-class families, even later when I attended university: they were more authentic and spontaneous.

While still a child, Antonioni was fond of drawing and music. A precocious violinist, he gave his first concert at the age of nine. Although he abandoned the violin with the discovery of cinema in his teens, drawing would remain a lifelong passion. “I have never drawn, even as a child, either puppets or silhouettes but rather facades of houses and gates. One of my favourite games consisted of organising towns. Ignorant in architecture, I constructed buildings and streets crammed with little figures. I invented stories for them. These childhood happenings – I was eleven years old – were like little films.” Upon graduation from the University of Bologna with a degree in economics, he started writing for the local Ferrara newspaper Il Corriere Padano in 1935 as a film journalist.

In 1940, Antonioni moved to Rome, where he worked for Cinema, the official Fascist film magazine edited by Vittorio Mussolini. However, Antonioni was fired a few months afterward. Later that year he enrolled at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia to study film technique, but left it after three months. He was drafted into the army afterwards. During the war Antonioni survived being condemned to death for his membership in the resistance. For a comprehensive account of Antonioni’s war time biography see “Michelangelo Antonioni’s ‘L’eclisse.'” Endnote No. 43.

Antonioni died aged 94 on 30 July 2007 in Rome, the same day that another renowned film director, Ingmar Bergman, also died. Antonioni lay in state at City Hall in Rome where a large screen showed black-and-white footage of him among his film sets and behind-the-scenes. He was buried in his home town of Ferrara on 2 August 2007. In 1942, Antonioni co-wrote A Pilot Returns with Roberto Rossellini and worked as assistant director on Enrico Fulchignoni’s I due Foscari. In 1943, he travelled to France to assist Marcel Carné on Les visiteurs du soir and then began a series of short films with Gente del Po (1943), a story of poor fishermen of the Po valley. After the Liberation, the film stock was stored in the East-Italian Fascist “Republic of Salò” and could not be recovered and edited until 1947 (the complete footage was never retrieved). These films were neorealist in style, being semi-documentary studies of the lives of ordinary people.

However, Antonioni’s first full-length feature film Cronaca di un amore (1950) broke away from neorealism by depicting the middle classes. He continued to do so in a series of other films: I vinti (“The Vanquished”, 1952), a trio of stories, each set in a different country (France, Italy and England), about juvenile delinquency; La signora senza camelie (The Lady Without Camellias, 1953) about a young film star and her fall from grace; and Le amiche (The Girlfriends, 1955) about middle class women in Turin. Il grido (The Outcry, 1957) was a return to working class stories, depicting a factory worker and his daughter. Each of these stories is about social alienation.

In Le Amiche (1955), Antonioni experimented with a radical new style: instead of a conventional narrative, he presented a series of apparently disconnected events, and he used long takes as part of his film making style. Antonioni returned to their use in L’avventura (1960), which became his first international success. At the Cannes Film Festival it received a mixture of cheers and boos, but the film was popular in art house cinemas around the world. La notte (1961), starring Jeanne Moreau and Marcello Mastroianni, and L’Eclisse (1962), starring Alain Delon, followed L’avventura. These three films are commonly referred to as a trilogy because they are stylistically similar and all concerned with the alienation of man in the modern world. La notte won the Golden Bear award at the 11th Berlin International Film Festival, His first color film, Il deserto rosso (The Red Desert, 1964), deals with similar themes, and is sometimes considered the fourth film of the “trilogy”. All of these films star Monica Vitti, his lover during that period.

Antonioni then signed a deal with producer Carlo Ponti that would allow artistic freedom on three films in English to be released by MGM. The first, Blowup (1966), set in Swinging London, was a major international success. The script was loosely based on the short story The Devil’s Drool (otherwise known as Blow Up) by Argentinian writer Julio Cortázar. Although it dealt with the challenging theme of the impossibility of objective standards and the ever-doubtable truth of memory, it was a successful and popular hit with audiences, no doubt helped by its sex scenes, which were explicit for the time. It starred David Hemmings and Vanessa Redgrave. The second film was Zabriskie Point (1970), his first set in America and with a counterculture theme. The soundtrack carried popular artists such as Pink Floyd (who wrote new music specifically for the film), the Grateful Dead and the Rolling Stones. However, its release was a critical and commercial disaster. The third, The Passenger (1975), starring Jack Nicholson and Maria Schneider, received critical praise, but also did poorly at the box office. It was out of circulation for many years, but was re-released for a limited theatrical run in October 2005 and has subsequently been released on DVD.

In 1972, in between Zabriskie Point and The Passenger, Antonioni was invited by the Mao government of the People’s Republic of China to visit the country. He made the documentary Chung Kuo, Cina, but it was severely denounced by the Chinese authorities as “anti-Chinese” and “anti-communist”. The documentary had its first showing in China on 25 November 2004 in Beijing with a film festival hosted by the Beijing Film Academy to honor the works of Michelangelo Antonioni.

In 1980, Antonioni made Il mistero di Oberwald (The Mystery of Oberwald), an experiment in the electronic treatment of color, recorded in video then transferred to film, featuring Monica Vitti once more. It is based on Jean Cocteau’s play L’Aigle à deux têtes (The Eagle With Two Heads). Identificazione di una donna (Identification of a Woman, 1982), filmed in Italy, deals one more time with the recursive subjects of his Italian trilogy. In 1985, Antonioni suffered a stroke, which left him partly paralyzed and unable to speak. However, he continued to make films, including Beyond the Clouds (1995), for which Wim Wenders filmed some scenes. As Wenders has explained, Antonioni rejected almost all the material filmed by Wenders during the editing, except for a few short interludes. They shared the FIPRESCI Prize at the Venice Film Festival with Cyclo.

In 1994 he was given the Honorary Academy Award “in recognition of his place as one of the cinema’s master visual stylists.” It was presented to him by Jack Nicholson. Months later, the statuette was stolen by burglars and had to be replaced. Previously, he had been nominated for Academy Awards for Best Director and Best Screenplay for Blowup. Antonioni’s final film, made when he was in his 90s, was a segment of the anthology film Eros (2004), entitled “Il filo pericoloso delle cose” (“The Dangerous Thread of Things”). The short film’s episodes are framed by dreamy paintings and the song “Michelangelo Antonioni”, composed and sung by Caetano Veloso. However, it was not well-received internationally; in America, for example, Roger Ebert claimed that it was neither erotic nor about eroticism. The U.S. DVD release of the film includes another 2004 short film by Antonioni, Lo sguardo di Michelangelo (The Gaze of Michelangelo).

Born

- September, 29, 1912

- Ferrara, Emilia Romagna, Italy

Died

- July, 30, 2007

- Rome, Italy

Cemetery

- Cimitero della Certosa

- Emilia-Romagna, Italy