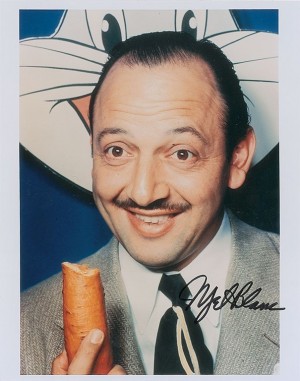

Mel Blanc (Melvin Jerome Blank)

Mel Blanc

Mel Blanc, the voice of Porky Pig, Bugs Bunny, Barney Rubble, Daffy Duck and countless other animated vertebrates, died Monday afternoon at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center.

He was 81 and had been hospitalized since May 19 suffering from heart disease and related medical problems, said hospital spokesman Ron Wise.

With Blanc when he died at 2:30 p.m. were his wife Estelle and son Noel, who now does most of his father’s voices.

Known as “The Man of 1,000 Voices,” Blanc was virtually never seen on the silver screen during the golden era of Merrie Melodies cartoons. Yet the myriad permutations of his acrobatic vocal cords have remained instantly recognizable by children of all ages around the globe for more than 50 years.

Among the many lines he repeatedly uttered that arguably rival those of Shakespeare in terms of familiarity, if not intellectual depth: “Eh . . . what’s up, Doc?” through the lips of the wiseacre hare, Bugs Bunny; “I tawt I taw a putty tat,” from the tart-tongued canary Tweety, and “SSSSSsssuffering SSSSSuccotash,” courtesy of Sylvester the sloppy cat. Not to mention Woody Woodpecker’s signature laugh (“Hee, hee, heh, hah, ho. Hee, hee, heh, hah, ho”); both the laconic train conductor (“Anaheim, Azusa and Cuc-a-monga”) and sputtering Maxwell auto of Jack Benny radio and TV show fame, and, of course, the stutter-strewn meanderings of Porky the wistful pig.

Over time, Blanc’s reknowned “voice characterizations” became nearly as much a part of his own life as breathing. In his later years, Blanc would often recount the scene as he lay in a coma at UCLA Medical Center following a nearly fatal 1961 car collision.

Bugs Bunny Invoked “They say that while I was unconscious, the doctor would come into my room each day and ask me how I was and, nothing. I wouldn’t answer him. So one day he comes into my room, he gets an idea, and he says, ‘Hey, Bugs Bunny! How are you?’ And they say I answered back in Bugs’ voice. “Ehh, just fine, Doc. How are you?”

The doctor then said, ” ‘And Porky Pig! How are you feeling?’ and I said, ‘J-j-j-just fine, th-th-th-thanks.’ “So you see, I actually live these characters.” For days following the head-on Sunset Boulevard collision, Blanc hovered near death. But like his dynamic cartoon characters — who so often slammed into walls and shrugged their shoulders or were blasted by dynamite and proceeded to calmly wipe the gunpowder off their noggins — Blanc, after 21 days, finally awoke, picked himself up and went back to work.

Although his lines were primarily written by others, Blanc’s performances, like those of the Three Stooges and Marx Brothers, gave life and technicolor to a spirit of wise-aleckness in an era of gray flannel suits and proper manners.

“For the majority of us, the sassiness of our childhood, muttered alone in bed or nursed in sullen silence at the dinner table, had a secret champion in the voices of Mel Blanc,” wrote Times comedy columnist Lawrence Christon in 1984.

Blanc, commenting on the personality of Bugs, put it in his own words: “He’s just a stinker. In other words, he’s more or less of the suppressed desire of what men would like to do that don’t have guts enough to do.”

Melvin Jerome Blanc was born May 30, 1908, in San Francisco, where his parents managed a ladies’ ready-to-wear apparel business.

Even as a youngster, he displayed his one-of-a-kind vocal gift, regaling his classmates and teachers with the piercing laugh he would later develop into Woody Woodpecker’s signature call.

“(In) high school, I used to laugh down the hall and hear the echo coming, you know. . . . So that’s the Woody Woodpecker laugh,” he once told an interviewer.

Blanc, whose family moved to Portland, Ore., shortly after his birth, turned immediately to show business following his graduation from high school in 1927. But for the first five years, he made his living with musical instruments rather than the magic of his vocal cords. An accomplished bassist, violinist and sousaphone player, Blanc played in the NBC Radio Orchestra and conducted the pit orchestra at the Orpheum Theatre in Portland.

In 1933, he married Estelle Rosenbaum, and soon after the couple began hosting a daily one-hour radio show in Portland called “Cobwebs and Nuts.” Since management would not spring to hire additional actors, Blanc invented an entire repertory company.

“They wouldn’t allow me to hire anybody else because they were too damn cheap,” he once said. ” . . . It taught me these many, many voices. This went on for two years. Finally my wife said to me, ‘You want to continue with the show or do you want to have a nervous breakdown?’ ”

Opting for sanity, Blanc, accompanied by his wife, moved to Los Angeles, where he toiled as a character actor on radio shows while repeatedly seeking an audition with Leon Schlesinger Productions, the cartoon company that produced the original Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies for Warner Bros.

Oral Test Passed At Schlesinger, Blanc was rebuffed several times by the same production supervisor. But the man finally died. So after more than a year of knocking on the door as persistently as Wile E. Coyote chasing the Road Runner, Blanc was offered an oral test by the supervisor’s successor.

The audition was rather unorthodox — at least for anyone other than a cartoon voice.

“One of the (directors) said, ‘Can you do a drunken bull?’ So I had to think for a moment and I said, ‘Yeah,’ . . . I’d shound, hic, like I was a little loaded, hic, and looking for the, hic, sour mash.”

Blanc did better than the Coyote ever did. He got the job, and the rest, as they say, was history.

Blanc’s first major memorable role was that of Porky Pig, which he was offered in 1937 after studio officials decided that the porcine personality, who was originally introduced in 1935, needed a face-lift.

“Leon called me in and asked me if I could do a pig — a fine thing to ask a Jewish kid,” Blanc recalled. “The guy they were using actually had a stutter and used up yards of film. But I could stutter and ad lib in rhythm.”

Bugs Bunny followed a year later. “They originally wanted to call Bugs Bunny the Happy Hare. But the writer was called Bugs Hardaway and had a snappy way about him. He’d say things like, ‘Hey, what’s cookin?’ I said, ‘Let’s use it. It’s modern.’ That became ‘What’s up, Doc?’ Bugs was a tough little stinker; that’s why I came up with a Brooklyn accent. I always worked on creating a vocal quality to match the characters.”

Blanc, indeed, was proud of his voices, proclaiming to interviewers: “I created every voice that I do (except Elmer Fudd). “I will not imitate. I think imitation is stealing from another person.”

In the case of Porky, Blanc claimed to have visited a pig farm and “wallowed around” for two weeks in order to “be real authentic.”

90% of Warner’s Stable In time, Blanc provided the voices for more than 90% of Warner’s stable of cartoon characters. For most of them, he helped develop the distinctive personas in tandem with such giants of the field as animator-directors Tex Avery, Chuck Jones and Robert McKimson.

“I create the personality when they tell me what the story is and so on,” he once explained. “Sylvester was sloppy. Tweety was a baby with a baby’s voice. Daffy was egotistical.”

Before signing an exclusive cartoon contract with Warners, Blanc also worked free lance for Walter Lantz, for whom he developed the laugh of Woody Woodpecker, and for Walt Disney. Unfortunately, his 16 days of work on Disney’s Pinocchio wound up on the cutting room floor, except for a single hiccup by a cat named “Giddy.”

It was one of the few cases in which Blanc was not successful. Blanc, in fact, eventually became the first voice specialist to earn over-the-title credits on cartoons.

Blanc later credited those credits with untapping a steady stream of radio work on such shows as Burns and Allen, Fibber McGee and Molly and Jack Benny.

On the Benny show, Blanc began with a growl — a bear growl. The bear was named Carmichael, and he guarded Benny’s vault.

“Well, I did the bear growl for six months, and that’s all I did was just the bear growl. Finally I said to him, ‘You know, Mr. Benny, I can also talk.’ ”

Benny quickly submitted, tabbing Blanc to do the train station announcer, a parrot who called Benny a cheapskate, a harried retail salesman, Benny’s exasperated violin teacher Prof. LeBlanc, and Cy from Tijuana, who answered most queries, “Si.”

When Benny went to TV, Blanc made the transition too, doing on-camera stints in his character roles. Blanc also had bit parts in several movies and starred in his own forgettable comedy CBS Radio network show in 1946, in which he played the owner of a fix-it shop.

In 1960, Blanc turned to made-for-TV cartoons, providing voices for a Saturday morning Bugs Bunny show and for two of the characters on “The Flintstones” — Barney Rubble and the pet dinosaur, Dino. For a time following his 1961 accident, Blanc taped his part at home with a microphone suspended over his bed.

In the following years, further TV cartoon roles included Secret Squirrel, Mr. Cosmo G. Spacely on “The Jetsons,” Hardy Har Har on “Lippy the Lion” and Droop-a-long on the “Magilla Gorilla Show.”

Over time, though, the quality of cartoons deteriorated as animation costs rose and writing values changed, Blanc reflected. “They’re not as funny as they used to be, and they seem like they’re just slapped together now,” Blanc said in 1975. ” . . . They’re playing too much just to the children, not enough to the adults . . . (and) they’re just not as animated as they should be.”

By that time, Blanc had diversified, forming his own production company, along with his son Noel. Since the early 1960s, the firm has produced commercials for such products as Kool Aid, Raid and Chrysler cars and for nonprofit agencies including the American Cancer Society. In 1988, Blanc performed a bit part as Daffy Duck in the wildly successful film feature, “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?”

Blanc also kept busy during his later years with his favorite hobby, collecting antique watches. His voluminous collection, insured for $150,000 as far back as 1972, contained items dating to 1510.

Over the years, Blanc received a slew of awards from civic organizations, many of which he was a member. Among the plaudits were United Jewish Welfare Fund Man of the Year and the Show Business Shrine Club’s first Life Achievement Award.

One of Blanc’s favored charities was the Shrine Hospital Children’s Burn Center where the family asks contributions in his name.

In 1984, Blanc was also honored by the Smithsonian Institution. During an informal ceremony in Washington, he revealed, “In real life, I sound most like Sylvester — without the spray.” Blanc also disclosed what he considered some of his more demanding challenges — Bugs Bunny imitating Elvis Presley and a Japanese native imitating Bugs Bunny.

“You know, my wife talks to me a lot about retiring,” he once told an interviewer. “I say to her, ‘What the hell for?’ I never want to stop. When I kick off, well, I kick off.”

Or, as Porky said over those many years: “Thaaaaaat’s all folks!”

Born

- May, 30, 1908

- San Francisco, California

Died

- July, 10, 1989

- Los Angeles, California

Cause of Death

- Heart disease & Emphysema

Cemetery

- Hollywood Forever Cemetery

- Hollywood,California