John Adams (John Adams)

John Adams

Adams, the eldest of three sons, was born on October 30, 1735 (October 19, 1735 Old Style, Julian calendar), in what is now Quincy, Massachusetts (then called the “north precinct” of Braintree, Massachusetts), to John Adams, Sr., and Susanna Boylston Adams. Adams’s birthplace is now part of Adams National Historical Park. His father (1691–1761) was a fifth-generation descendant of Henry Adams, who emigrated from Somerset in England to Massachusetts Bay Colony in about 1638. The elder Adams, the descendant of Puritans, continued in this religious tradition by serving as a Congregationalist deacon; he also farmed and served as a lieutenant in the militia. Further he served as a selectman, or town councilman, and supervised the building and planning of schools and roads. Adams commonly praised his father and indicated that he and his father were very close when he was a child. Susanna Boylston Adams was a member of one of the colony’s leading medical families, the Boylstons of Brookline. Though raised in materially modest surroundings, Adams felt acutely that he had a responsibility to live up to his family heritage: he was a direct descendent of the founding generation of Puritans, who came to the American wilderness in the 1630s, established colonial presence in America, and had a profound effect on the culture, laws, and traditions of their region. Journalist Richard Brookhiser, drawing on the relevant historiography, has written that these Puritan ancestors of Adams’s “believed they lived in the Bible. England under the Stuarts was Egypt; they were Israel fleeing … to establish a refuge for godliness, a city upon a hill.” By the time of John Adams’ birth in 1735, Puritan tenets such as predestination were no longer as widely accepted, and many of their stricter practices had mellowed with time, but John Adams “considered them bearers of freedom, a cause that still had a holy urgency.” It was a value system he believed in, and a heroic model he wished to live up to.

Young Adams went to Harvard College at age sixteen in 1751. His father expected him to become a minister, but Adams had doubts. After graduating in 1755 with an A.B., he taught school for a few years in Worcester, Massachusetts, allowing himself time to think about his career choice. After much reflection, he decided to become a lawyer, writing his father that he found among lawyers “noble and gallant achievements” but among the clergy, the “pretended sanctity of some absolute dunces.” He later became a Unitarian, and dropped belief in predestination, eternal damnation, the divinity of Christ, and most other Calvinist beliefs of his Puritan ancestors. Adams then studied law in the office of John Putnam, the leading lawyer in Worcester. In 1758, after earning an A.M. from Harvard, Adams was admitted to the bar. From an early age, he developed the habit of writing descriptions of events and impressions of men which are scattered through his diary. He put the skill to good use as a lawyer, often recording cases he observed so that he could study and reflect upon them. His report of the 1761 argument of James Otis in the Massachusetts Superior Court as to the legality of Writs of Assistance is a good example. Otis’s argument inspired Adams with zeal for the cause of the American colonies. On October 25, 1764, five days before his 29th birthday, Adams married Abigail Smith (1744–1818), his third cousin and the daughter of a Congregational minister, Rev. William Smith, at Weymouth, Massachusetts. Their children were Abigail (1765–1813); future president John Quincy Adams (1767–1848); Susanna (1768–1770); Charles (1770–1800); Thomas Boylston (1772–1832); and Elizabeth (1777). Adams was not a popular leader like his second cousin, Samuel Adams. Instead, his influence emerged through his work as a constitutional lawyer and his intense analysis of historical examples, together with his thorough knowledge of the law and his dedication to the principles of republicanism. Adams often found his inborn contentiousness to be a constraint in his political career.

Adams first rose to prominence as an opponent of the Stamp Act 1765, which was imposed by the British Parliament without consulting the American legislatures. Americans protested vehemently that it violated their traditional rights as Englishmen. Popular resistance, he later observed, was sparked by an oft-reprinted sermon of the Boston minister, Jonathan Mayhew, interpreting Romans 13 to elucidate the principle of just insurrection. In 1765, Adams drafted the instructions which were sent by the inhabitants of Braintree to its representatives in the Massachusetts legislature, and which served as a model for other towns to draw up instructions to their representatives. In August 1765, he anonymously contributed four notable articles to the Boston Gazette (republished in The London Chronicle in 1768 as True Sentiments of America, also known as A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law). In the letter he suggested that there was a connection between the Protestant ideas that Adams’ Puritan ancestors brought to New England and the ideas behind their resistance to the Stamp Act. In the former he explained that the opposition of the colonies to the Stamp Act was because the Stamp Act deprived the American colonists of two basic rights guaranteed to all Englishmen, and which all free men deserved: rights to be taxed only by consent and to be tried only by a jury of one’s peers. The “Braintree Instructions” were a succinct and forthright defense of colonial rights and liberties, while the Dissertation was an essay in political education. In December 1765, he delivered a speech before the governor and council in which he pronounced the Stamp Act invalid on the ground that Massachusetts, being without representation in Parliament, had not assented to it.

In 1770, a street confrontation resulted in British soldiers killing five civilians in what became known as the Boston Massacre. The soldiers involved were arrested on criminal charges. Not surprisingly, they had trouble finding legal counsel to represent them. Finally, they asked Adams to organize their defense. He accepted, though he feared it would hurt his reputation. In their defense, Adams made his now famous quote regarding making decisions based on the evidence: “Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence.” He also offered a now-famous, detailed defense of Blackstone’s Ratio: It is more important that innocence be protected than it is that guilt be punished, for guilt and crimes are so frequent in this world that they cannot all be punished. But if innocence itself is brought to the bar and condemned, perhaps to die, then the citizen will say, “whether I do good or whether I do evil is immaterial, for innocence itself is no protection,” and if such an idea as that were to take hold in the mind of the citizen that would be the end of security whatsoever. Six of the soldiers were acquitted. Two who had fired directly into the crowd were charged with murder but were convicted only of manslaughter. Adams was paid only a small sum by the British soldiers. Despite his previous misgivings, Adams was elected to the Massachusetts General Court (the colonial legislature) in June 1770, while still in preparation for the trial.

While Washington won the presidential election of 1789 with 69 votes in the electoral college, Adams came in second with 34 votes and became Vice President. According to David McCullough, what he really might have wanted was to be the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. He presided over the Senate but otherwise played a minor role in the politics of the early 1790s; he was reelected Vice President in 1792. Washington seldom asked Adams for input on policy and legal issues during his tenure as vice president. At the start of Washington’s administration, Adams became deeply involved in a month-long Senate controversy over the official title of the President. Adams favored grandiose titles such as “His Majesty the President” or “His High Mightiness, the President of the United States and Protector of Their Liberties.” The plain “President of the United States” eventually won the debate. The perceived pomposity of his stance, along with his being overweight, led to Adams earning the nickname “His Rotundity.” As president of the Senate, Adams cast 29 tie-breaking votes—a record that only John C. Calhoun came close to tying, with 28. His votes protected the president’s sole authority over the removal of appointees and influenced the location of the national capital. On at least one occasion, he persuaded senators to vote against legislation that he opposed, and he frequently lectured the Senate on procedural and policy matters. Adams’ political views and his active role in the Senate made him a natural target for critics of the Washington administration. Toward the end of his first term, as a result of a threatened resolution that would have silenced him except for procedural and policy matters, he began to exercise more restraint. When the two political parties formed, he joined the Federalist Party, but never got on well with its dominant leader Alexander Hamilton. Because of Adams’ seniority and the need for a northern president, he was elected as the Federalist nominee for president in 1796, over Thomas Jefferson, the leader of the opposition Democratic-Republican Party. His success was due to peace and prosperity; Washington and Hamilton had averted war with Britain with the Jay Treaty of 1795. Adams’ two terms as Vice President were frustrating experiences for a man of his vigor, intellect, and vanity. He complained to his wife Abigail, “My country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived.”

The 1796 election was the first contested election under the First Party System. Adams was the presidential candidate of the Federalist Party and Thomas Pinckney, the Governor of South Carolina, was also running as a Federalist (at this point, the vice president was whoever came in second, so no running mates existed in the modern sense). The Federalists wanted Adams as their presidential candidate to crush Thomas Jefferson’s bid. Most Federalists would have preferred Hamilton to be a candidate. Although Hamilton and his followers supported Adams, they also held a grudge against him. They did consider him to be the lesser of the two evils. However, they thought Adams lacked the seriousness and popularity that had caused Washington to be successful and feared that Adams was too vain, opinionated, unpredictable, and stubborn to follow their directions. Adams’ opponents were former Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson of Virginia, who was joined by Senator Aaron Burr of New York on the Democratic-Republican ticket. As was customary, Adams stayed in his home town of Quincy rather than actively campaign for the Presidency. He wanted to stay out of what he called the silly and wicked game. His party, however, campaigned for him, while the Democratic-Republicans campaigned for Jefferson. It was expected that Adams would dominate the votes in New England, while Jefferson was expected to win in the Southern states. In the end, Adams won the election by a narrow margin of 71 electoral votes to 68 for Jefferson (who became the vice president).

As President, Adams followed Washington’s lead in making the presidency the example of republican values, and stressing civic virtue; he was never implicated in any scandal. Adams continued not just the Washington cabinet but all the major programs of the Washington Administration as well. Adams continued to strengthen the central government, in particular by expanding the navy and army. His economic programs were a continuation of those of Hamilton, who regularly consulted with key cabinet members, especially the powerful Secretary of the Treasury, Oliver Wolcott, Jr.[79] Historians debate his decision to keep the Washington cabinet. Though they were very close to Hamilton, their retention ensured a smoother succession.[80] He remained quite independent of his cabinet throughout his term, often making decisions despite strong opposition from it. It was out of this management style that he avoided war with France, despite a strong desire among his cabinet secretaries for war. The Quasi-War with France resulted in the disentanglement with European affairs that Washington had sought. It also, like other conflicts, had enormous psychological benefits, as America saw itself as holding its own against a European power.

Historian George Herring argues that Adams was the most independent-minded of all the founders. Though he aligned with the Federalists, he was more his own party, disagreeing with the Federalists almost as much as he did the Democratic-Republican opposition. Though often described as “prickly”, his independence meant that he had a talent for making good decisions in the face of almost universal hostility. Indeed, it was Adams’ decision to push for peace with France, rather than to continue hostilities, that hurt his popularity. Though this decision played an important role in his reelection defeat, he was ultimately thrilled with that decision, so much so that he had it engraved on his tombstone. Adams spent much of his term at his home in Massachusetts, ignoring the details of political patronage that were not ignored by others. Adams’ combative spirit did not always lend itself to presidential decorum, as Adams himself admitted in his old age: “[As president] I refused to suffer in silence. I sighed, sobbed, and groaned, and sometimes screeched and screamed. And I must confess to my shame and sorrow that I sometimes swore.”

Following his 1800 defeat, Adams retired into private life. Depressed when he left office, he did not attend Jefferson’s inauguration, making him one of only four surviving presidents (i.e., those who did not die in office) not to attend his successor’s inauguration. Interestingly, one of the other three was his son, John Quincy Adams. Adams’ correspondence with Jefferson at the time of the transition suggests that he did not feel the animosity or resentment that later scholars have attributed to him. He left Washington before Jefferson’s inauguration as much out of sorrow at the death of his son Charles Adams (due in part to the younger man’s alcoholism) and his desire to rejoin his wife Abigail, who had left for Massachusetts months before the inauguration. Adams resumed farming at his home, Peacefield, in the town of Quincy (formerly a part of the town of Braintree, as it was earlier in his life). He began to work on an autobiography (which he never finished), and resumed correspondence with such old friends as Benjamin Waterhouse and Benjamin Rush. He also began a bitter and resentful correspondence with an old family friend, Mercy Otis Warren, protesting how in her 1805 history of the American Revolution she had, in his view, caricatured his political beliefs and misrepresented his services to the country. Primarily, this revolved around a dispute about whether Adams was sufficiently republican in Warren’s view, instead of monarchical, and was related to the Federalist/Republican political divide. After Jefferson’s retirement from public life in 1809 after two terms as President, Adams became more vocal. For three years he published a stream of letters in the Boston Patriot newspaper, presenting a long and almost line-by-line refutation of an 1800 pamphlet by Hamilton attacking his conduct and character. Though Hamilton had died in 1804 from a mortal wound sustained in his notorious duel with Aaron Burr, Adams felt the need to vindicate his character against the New Yorker’s vehement attacks. Adams’ retirement, at twenty-five years, four months, was the longest retirement of any president until Herbert Hoover surpassed the mark on August 5, 1958. His retirement currently ranks as the fourth longest, after Jimmy Carter (33 years, 134 days to date), Hoover (31 years, 230 days) and Gerald Ford (29 years, 340 days). Interestingly, all four Presidents who have lived more than twenty-five years after their Presidency have been single-term Presidents (or less, in the case of Ford).

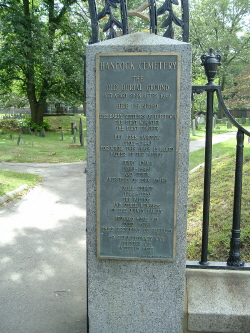

Less than a month before his death, John Adams issued a statement about the destiny of the United States, which historians such as Joy Hakim have characterized as a “warning” for his fellow citizens. Adams said: My best wishes, in the joys, and festivities, and the solemn services of that day on which will be completed the fiftieth year from its birth, of the independence of the United States: a memorable epoch in the annals of the human race, destined in future history to form the brightest or the blackest page, according to the use or the abuse of those political institutions by which they shall, in time to come, be shaped by the human mind. On Tuesday, July 4, 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, at approximately 6:20 PM, Adams died at his home in Quincy. Told that it was the Fourth, he answered clearly, “It is a great day. It is a good day.”[citation needed] Relatives who were at his bedside reported that his last words were “Jefferson survives”; news of Jefferson’s death earlier that day did not reach Boston until after Adams’ death. Adams and Jefferson are the only two Presidents to die on the same day; the nearest two other presidents have died to each other was 27 days apart (between Harry S. Truman on December 26, 1972, and Lyndon B. Johnson on January 22, 1973). His death left Charles Carroll of Carrollton as the last surviving signatory of the Declaration of Independence. Adams’ crypt lies at United First Parish Church (also known as the Church of the Presidents) in Quincy, the site of his funeral was held on July 7. He and Abigail had originally been buried in Hancock Cemetery, across the road from the Church. News of his death did not reach his son, the President, until Sunday, July 9, near Baltimore, after he had received word to hurry back to Boston earlier in the day. The younger Adams, in fact, knew about Jefferson’s death before his own father’s. Until the older Adams’ record was broken by Ronald Reagan in 2001, he was the nation’s longest-living President (90 years, 247 days) maintaining that record for 175 years. Adams is currently the third longest-living president, behind Reagan and Gerald R. Ford, who lived forty-five days longer than Reagan. Adams also held the title of oldest living President longer than anyone until Hoover again passed his record on July 27, 1959. Adams is still behind only Hoover in that mark.

Born

- October, 30, 1735

- Quincy, Massachusetts

Died

- July, 04, 1826

- Quincy, Massachusetts

Cause of Death

- debility (old age; most likely heart failure caused by arteriosclerosis)

Cemetery

- Hancock Cemetery

- Quincy, Massachusetts