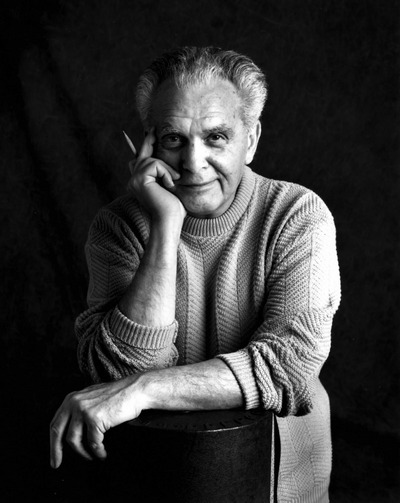

Jack Kirby (Jack Kirby)

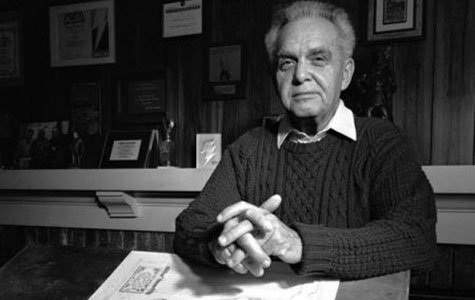

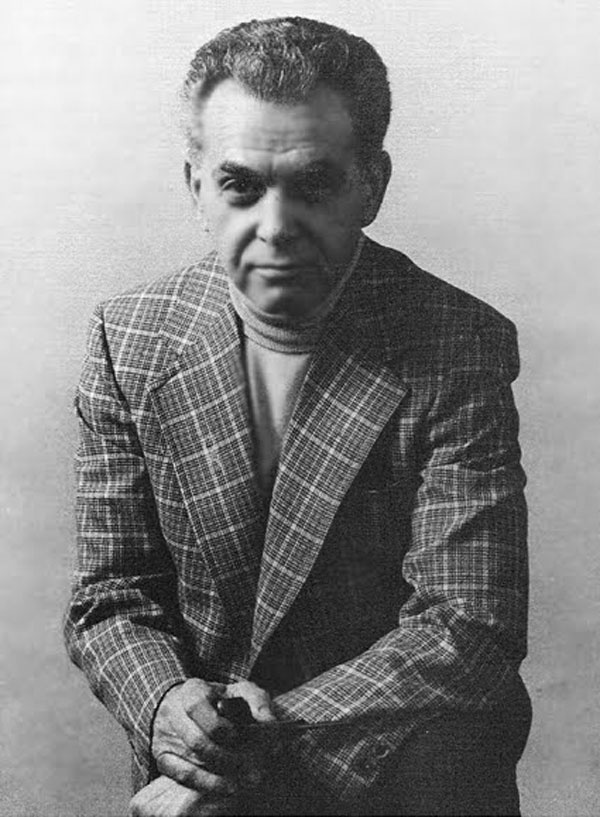

Jack Kirby was born Jacob Kurtzberg on August 28, 1917, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan in New York City, where he was raised. His parents, Rose and Benjamin Kurtzberg, were Austrian Jewish immigrants, and his father earned a living as a garment factory worker. In his youth, Kirby desired to escape his neighborhood. He liked to draw, and sought out places he could learn more about art. Essentially self-taught, Kirby cited among his influences the comic strip artists Milton Caniff, Hal Foster, and Alex Raymond, as well as such editorial cartoonists as C. H. Sykes, “Ding” Darling, and Rollin Kirby. He was rejected by the Educational Alliance because he drew “too fast with charcoal”, according to Kirby. He later found an outlet for his skills by drawing cartoons for the newspaper of the Boys Brotherhood Republic, a “miniature city” on East 3rd Street where street kids ran their own government.

At age 14, Kirby enrolled at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, leaving after a week. “I wasn’t the kind of student that Pratt was looking for. They wanted people who would work on something forever. I didn’t want to work on any project forever. I intended to get things done”.

Kirby joined the Lincoln Newspaper Syndicate in 1936, working there on newspaper comic strips and on single-panel advice cartoons such as Your Health Comes First!!! (under the pseudonym Jack Curtiss). He remained until late 1939, when he began working for the movie animation company Fleischer Studios as an inbetweener (an artist who fills in the action between major-movement frames) on Popeye cartoons. “I went from Lincoln to Fleischer,” he recalled. “From Fleischer I had to get out in a hurry because I couldn’t take that kind of thing,” describing it as “a factory in a sense, like my father’s factory. They were manufacturing pictures.”

Around that time, the American comic book industry was booming. Kirby began writing and drawing for the comic-book packager Eisner & Iger, one of a handful of firms creating comics on demand for publishers. Through that company, Kirby did what he remembers as his first comic book work, for Wild Boy Magazine. This included such strips as the science fiction adventure “The Diary of Dr. Hayward” (under the pseudonym Curt Davis), the Western crimefighter feature “Wilton of the West” (as Fred Sande), the swashbuckler adventure “The Count of Monte Cristo” (again as Jack Curtiss), and the humor features “Abdul Jones” (as Ted Grey) and ‘”Socko the Seadog” (as Teddy), all variously for Jumbo Comics and other Eisner-Iger clients. He first used the surname Kirby as the pseudonymous Lance Kirby in two “Lone Rider” Western stories in Eastman Color’s Famous Funnies #63-64 (Oct.-Nov. 1939). He ultimately settled on the pen name Jack Kirby because it reminded him of actor James Cagney. However, he took offense to those who suggested he changed his name in order to hide his Jewish heritage.

In the summer of 1940, Kirby and his family moved to Brooklyn. There, Kirby met Rosalind “Roz” Goldstein, who lived in the same apartment building. The pair began dating soon afterward. Kirby proposed to Goldstein on her eighteenth birthday, and the two became engaged.

Kirby moved on to comic-book publisher and newspaper syndicator Fox Feature Syndicate, earning a then-reasonable $15-a-week salary. He began to explore superhero narrative with the comic strip The Blue Beetle, published from January to March 1940, starring a character created by the pseudonymous Charles Nicholas, a house name that Kirby retained for the three-month-long strip. During this time, Kirby met and began collaborating with cartoonist and Fox editor Joe Simon, who in addition to his staff work continued to freelance. Simon recalled in 1988, “I loved Jack’s work and the first time I saw it I couldn’t believe what I was seeing. He asked if we could do some freelance work together. I was delighted and I took him over to my little office. We worked from the second issue of Blue Bolt through… about 25 years.”

After leaving Fox and landing at pulp magazine publisher Martin Goodman’s Timely Comics (later to become Marvel Comics), Simon and Kirby created the patriotic superhero Captain America in late 1940. Simon cut a deal with Goodman that gave him and Kirby 25 percent of the profits from the feature, as well as salaried positions as the company’s editor and art director, respectively. The first issue of Captain America Comics, released in early 1941, sold out in days, and the second issue’s print run was set at over a million copies. The title’s success established the team as a notable creative force in the industry. After the first issue was published, Simon asked Kirby to join the Timely staff as the company’s art director.

With the success of the Captain America character, Simon felt that Goodman was not paying the pair the promised percentage of profits, and so sought work for the two of them at National Comics (later renamed DC Comics). Kirby and Simon negotiated a deal that would pay them a combined $500 a week, as opposed to the $75 and $85 they respectively earned at Timely. Fearing that Goodman would not pay them if he found out they were moving to National, the pair kept the deal a secret with Stan Lee while they continued producing work for the company. Goodman eventually learned of the deal, and Kirby and Simon, convinced that Lee had revealed their plans, left after completing their work on Captain America Comics #10.

Kirby and Simon spent their first weeks at National trying to devise new characters while the company sought how best to utilize the pair. After a few failed editor-assigned ghosting assignments, National’s Jack Liebowitz told them to “just do what you want”. The pair then revamped the Sandman feature in Adventure Comics and created the superhero Manhunter. In July 1942 they began the Boy Commandos feature. The ongoing “kid gang” series of the same name, launched later that same year, was the creative team’s first National feature to graduate into its own title. It sold over a million copies a month, becoming National’s third best-selling title. They also scored a hit with the homefront kid-gang team, the Newsboy Legion, featuring in Star-Spangled Comics.

Kirby married Roz Goldstein on May 23, 1942. With World War II underway, Liebowitz expected that Simon and Kirby would be drafted, so he asked the artists to create an inventory of material to be published in their absence. The pair hired writers, inkers, letterers, and colorists in order to create a year’s worth of material. Kirby was drafted into the U.S. Army on June 7, 1943. After basic training at Camp Stewart, near Savannah, Georgia, he was assigned to Company F of the 11th Infantry Regiment. He landed on Omaha Beach in Normandy on August 23, 1944, two-and-a-half months after D-Day, though Kirby’s reminiscences would place his arrival just 10 days after. Kirby recalled that a lieutenant, learning that comics artist Kirby was in his command, made him a scout who would advance into towns and draw reconnaissance maps and pictures, an extremely dangerous duty.

Kirby and his wife corresponded regularly by v-mail, with Roz sending “him a letter a day” while she worked in a lingerie shop and lived with her mother at 2820 Brighton 7th Street in Brooklyn. During the winter of 1944, Kirby suffered severe frostbite on his lower extremities and was taken to a hospital in London, England, for recovery. Doctors considered amputating Kirby’s legs, but he eventually recovered from the frostbite. He returned to the United States in January 1945, assigned to Camp Butner in North Carolina, where he spent the last six months of his service as part of the motor pool. Kirby was honorably discharged as a Private First Class on July 20, 1945, having received a Combat Infantryman Badge and a European/African/Middle Eastern Theater ribbon with a bronze battle star.

Simon arranged for work for Kirby and himself at Harvey Comics, where, through the early 1950s, the duo created such titles as the kid-gang adventure Boy Explorers Comics, the kid-gang Western Boys’ Ranch, the superhero comic Stuntman, and, in vogue with the fad for 3-D movies, Captain 3-D. Simon and Kirby additionally freelanced for Hillman Periodicals (the crime fiction comic Real Clue Crime) and for Crestwood Publications (Justice Traps The Guilty).

The team found its greatest success in the postwar period by creating romance comics. Simon, inspired by Macfadden Publications’ romantic-confession magazine True Story, transplanted the idea to comic books and with Kirby created a first-issue mock-up of Young Romance. Showing it to Crestwood general manager Maurice Rosenfeld, Simon asked for 50% of the comic’s profits. Crestwood publishers Teddy Epstein and Mike Bleier agreed, stipulating that the creators would take no money up front. Young Romance #1 (cover-date Oct. 1947) “became Jack and Joe’s biggest hit in years”. Indeed, the pioneering title sold a staggering 92% of its print run, inspiring Crestwood to increase the print run by the third issue to triple the initial number of copies. Initially published bimonthly, Young Romance quickly became a monthly title and produced the spin-off Young Love—together the two titles sold two million copies per month, according to Simon—later joined by Young Brides and In Love, the latter “featuring full-length romance stories”. Young Romance spawned dozens of imitators from publishers such as Timely, Fawcett, Quality, and Fox Feature Syndicate. Despite the glut, the Simon & Kirby romance titles continued to sell millions of copies a month, which allowed Kirby to buy a house for his family in Mineola, Long Island, New York in 1949, which would be the family’s home for the next 20 years, working out of a basement studio 10 feet in width, which the family referred to as “The Dungeon”.

Bitter that Timely Comics’ 1950s iteration, Atlas Comics, had relaunched Captain America in a new series in 1954, Kirby and Simon created Fighting American. Simon recalled, “We thought we’d show them how to do Captain America”. While the comic book initially portrayed the protagonist as an anti-Communist dramatic hero, Simon and Kirby turned the series into a superhero satire with the second issue, in the aftermath of the Army-McCarthy hearings and the public backlash against the Red-baiting U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy.

At the urging of a Crestwood salesman, Kirby and Simon launched their own comics company, Mainline Publications, securing a distribution deal with Leader News in late 1953 or early 1954, subletting space from their friend Al Harvey’s Harvey Publications at 1860 Broadway. Mainline, which existed from 1954 to 1955, published four titles: the Western Bullseye: Western Scout; the war comic Foxhole, since EC Comics and Atlas Comics were having success with war comics, but promoting theirs as being written and drawn by actual veterans; In Love, since their earlier romance comic Young Love was still being widely imitated; and the crime comic Police Trap, which claimed to be based on genuine accounts by law-enforcement officials. After the duo rearranged and republished artwork from an old Crestwood story in In Love, Crestwood refused to pay the team, who sought an audit of Crestwood’s finances. Upon review, the pair’s attorney’s stated the company owed them $130,000 for work done over the past seven years. Crestwood paid them $10,000 in addition to their recent delayed payments. However, the partnership between Kirby and Simon had become strained. Simon left the industry for a career in advertising, while Kirby continued to freelance. “He wanted to do other things and I stuck with comics,” Kirby recalled in 1971. “It was fine. There was no reason to continue the partnership and we parted friends.”

At this point in the mid-1950s, Kirby made a temporary return to the former Timely Comics, now known as Atlas Comics, the direct predecessor of Marvel Comics. Inker Frank Giacoia had approached editor-in-chief Stan Lee for work and suggested he could “get Kirby back here to pencil some stuff.” While also freelancing for National Comics, the future DC Comics, Kirby drew 20 stories for Atlas from 1956 to 1957: Beginning with the five-page “Mine Field” in Battleground #14 (Nov.1956), Kirby penciled and in some cases also inked (with his wife, Roz) and wrote stories of the Western hero Black Rider, the Fu Manchu-like Yellow Claw, and more. But in 1957, distribution troubles caused the “Atlas implosion” that resulted in several series being dropped and no new material being assigned for many months. It would be the following year before Kirby returned to the nascent Marvel.

For DC around this time, Kirby co-created with writers Dick and Dave Wood the non-superpowered adventuring quartet the Challengers of the Unknown in Showcase #6 (Feb. 1957), while also contributing to such anthologies asHouse of Mystery. During 30 months freelancing for DC, Kirby drew slightly more than 600 pages, which included 11 six-page Green Arrow stories in World’s Finest Comics and Adventure Comics that, in a rarity, Kirby inked himself. Kirby recast the archer as a science-fiction hero, moving him away from his Batman-formula roots, but in the process alienating Green Arrow co-creator Mort Weisinger.

He also began drawing a newspaper comic strip, Sky Masters of the Space Force, written by the Wood brothers and initially inked by the unrelated Wally Wood. Kirby left National Comics due largely to a contractual dispute in which editor Jack Schiff, who had been involved in getting Kirby and the Wood brothers the Sky Masters contract, claimed he was due royalties from Kirby’s share of the strip’s profits. Schiff successfully sued Kirby. Some DC editors also had criticized him over art details, such as not drawing “the shoelaces on a cavalryman’s boots” and showing a Native American “mounting his horse from the wrong side.”

Several months later, after his split with DC, Kirby began freelancing regularly for Atlas in spite of his lingering resentment of Lieber’s earlier treatment of him in the 1940s. Because of the poor page rates, Kirby would spend 12 to 14 hours daily at his drawing table at home, producing eight to ten pages of artwork a day. His first published work at Atlas was the cover of and the seven-page story “I Discovered the Secret of the Flying Saucers” in Strange Worlds #1 (Dec. 1958). Initially with Christopher Rule as his regular inker, and later Dick Ayers, Kirby drew across all genres, from romance comics to war comics to crime comics to Westerns, but made his mark primarily with a series of supernatural-fantasy and science fiction stories featuring giant, drive-in movie-style monsters with names like Groot, the Thing from Planet X; Grottu, King of the Insects; and Fin Fang Foom for the company’s many anthology series, such as Amazing Adventures, Strange Tales, Tales to Astonish, Tales of Suspense, and World of Fantasy. His bizarre designs of powerful, unearthly creatures proved a hit with readers. Additionally, he also freelanced for Archie Comics’ around this time, reuniting briefly with Joe Simon to help develop the series The Fly and The Double Life of Private Strong. Additionally, Kirby drew some issues of Classics Illustrated.

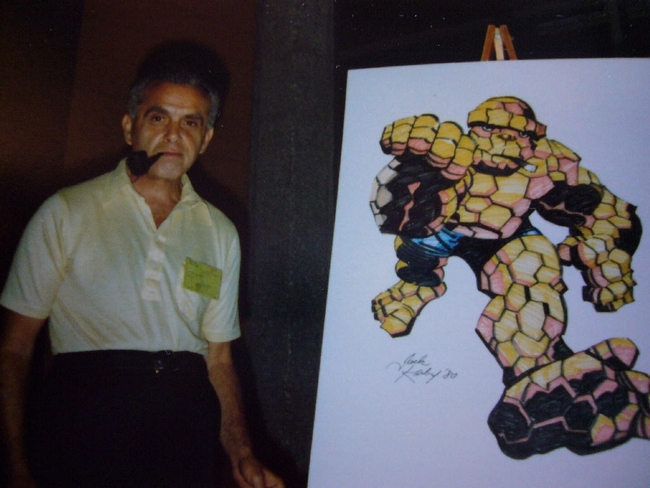

It was at Marvel, however, with writer and editor-in-chief Lee, that Kirby hit his stride once again in superhero comics, beginning with The Fantastic Four #1 (Nov. 1961). The landmark series became a hit that revolutionized the industry with its comparative naturalism and, eventually, a cosmic purview informed by Kirby’s seemingly boundless imagination—one well-matched with the consciousness-expanding youth culture of the 1960s.

For almost a decade, Kirby provided Marvel’s house style, co-creating with Stan Lee many of the Marvel characters and designing their visual motifs. At Lee’s request, he often provided new-to-Marvel artists “breakdown” layouts, over which they would pencil in order to become acquainted with the Marvel look. As artist Gil Kane described:

Jack was the single most influential figure in the turnaround in Marvel’s fortunes from the time he rejoined the company … It wasn’t merely that Jack conceived most of the characters that are being done, but … Jack’s point of view and philosophy of drawing became the governing philosophy of the entire publishing company and, beyond the publishing company, of the entire field … [Marvel took] Jack and use[d] him as a primer. They would get artists … and they taught them the ABCs, which amounted to learning Jack Kirby. … Jack was like the Holy Scripture and they simply had to follow him without deviation. That’s what was told to me … It was how they taught everyone to reconcile all those opposing attitudes to one single master point of view.

Highlights other than the Fantastic Four include: Thor, the Hulk, Iron Man, the original X-Men, the Silver Surfer, Doctor Doom, Galactus, Uatu the Watcher, Magneto, Ego the Living Planet, the Inhumans and their hidden city of Attilan, and the Black Panther—comics’ first known black superhero—and his African nation of Wakanda. Simon and Kirby’s Captain America was also incorporated into Marvel’s continuity with Kirby approving Lee’s idea of partially remaking the character as a man out of his time and regretting the death of his sidekick.

In 1968 and 1969, Joe Simon was involved in litigation with Marvel Comics over the ownership of Captain America, initiated by Marvel after Simon registered the copyright renewal for Captain America in his own name. According to Simon, Kirby agreed to support the company in the litigation and, as part of a deal Kirby made with publisher Martin Goodman, signed over to Marvel any rights he might have had to the character.

Kirby continued to expand the medium’s boundaries, devising photo-collage covers and interiors, developing new drawing techniques such as the method for depicting energy fields now known as “Kirby Dots”, and other experiments. Yet he grew increasingly dissatisfied with working at Marvel. There have been a number of reasons given for this dissatisfaction, including resentment over Stan Lee’s increasing media prominence, a lack of full creative control, anger over breaches of perceived promises by publisher Martin Goodman, and frustration over Marvel’s failure to credit him specifically for his story plotting and for his character creations and co-creations. He began to both script and draw some secondary features for Marvel, such as “The Inhumans” in Amazing Adventures, as well as horror stories for the anthology title Chamber of Darkness, and received full credit for doing so; but in 1970, Kirby was presented with a contract that included such unfavorable terms as a prohibition against legal retaliation. When Kirby objected, the management refused to negotiate any contract changes. Kirby, although he was earning $35,000 a year freelancing for the company, subsequently left Marvel in 1970 for rival DC Comics, under editorial director Carmine Infantino.

Kirby spent nearly two years negotiating a deal to move to DC Comics, where in late 1970 he signed a three-year contract with an option for two additional years. He produced a series of interlinked titles under the blanket sobriquet “The Fourth World”, which included a trilogy of new titles — New Gods, Mister Miracle, and The Forever People — as well as the extant Superman’s Pal Jimmy Olsen. Kirby picked the latter book because the series was without a stable creative team and he did not want to cost anyone a job. The central villain of the Fourth World series, Darkseid, and some of the Fourth World concepts, appeared in Jimmy Olsen before the launch of the other Fourth World books, giving the new titles greater exposure to potential buyers. The Superman figures and Jimmy Olsen faces drawn by Kirby were redrawn by Al Plastino, and later by Murphy Anderson. In 2007, comics writer Grant Morrison commented that “Kirby’s dramas were staged across Jungian vistas of raw symbol and storm…The Fourth World saga crackles with the voltage of Jack Kirby’s boundless imagination let loose onto paper.”

An attempt at creating new formats for comics produced the one-shot black-and-white magazines Spirit World and In the Days of the Mob in 1971.

Kirby later produced other DC features such as OMAC, Kamandi, The Demon, “The Losers”, “Dingbats of Danger Street”, Kobra and, together with former partner Joe Simon for one last time, a new incarnation of the Sandman.

Kirby’s production assistant of the time, Mark Evanier, recounted that DC’s policies of the era were not in synch with Kirby’s creative impulses, and that he was often forced to work on characters and projects that he did not want to work on.

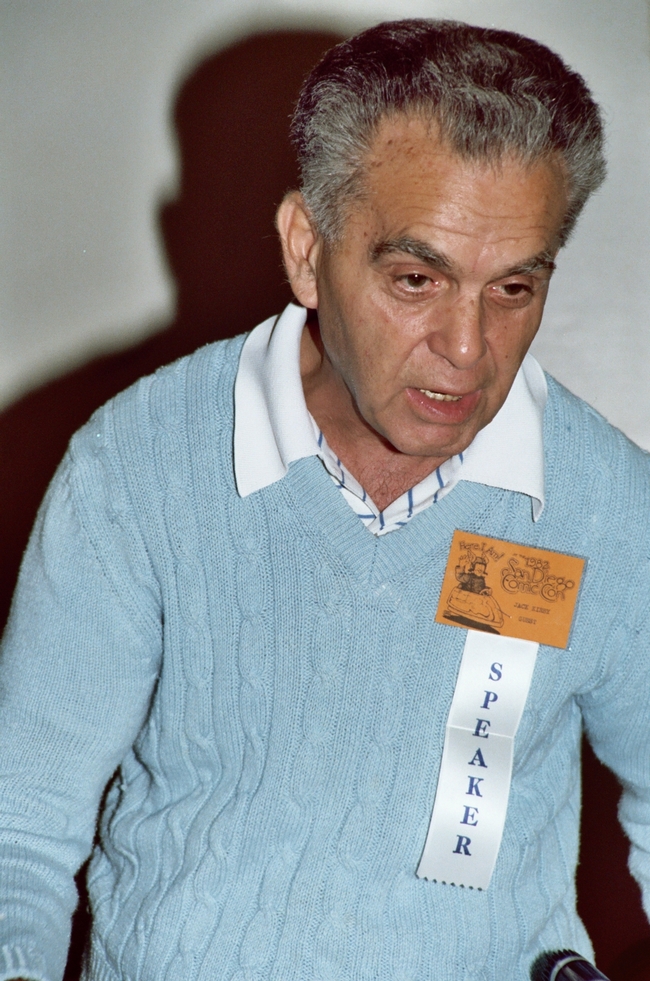

At the comic book convention Marvelcon ’75, in spring 1975, Stan Lee used a Fantastic Four panel discussion to announce that Kirby was returning to Marvel after having left in 1970 to work for DC Comics. Lee wrote in his monthly column, “Stan Lee’s Soapbox”, that, “I mentioned that I had a special announcement to make. As I started telling about Jack’s return, to a totally incredulous audience, everyone’s head started to snap around as Kirby himself came waltzin’ down the aisle to join us on the rostrum! You can imagine how it felt clownin’ around with the co-creator of most of Marvel’s greatest strips once more.”

Back at Marvel, Kirby both wrote and drew the monthly Captain America series as well as the Captain America’s Bicentennial Battles one-shot in the oversized treasury format. He created the series The Eternals, which featured a race of inscrutable alien giants, the Celestials, whose behind-the-scenes intervention in primordial humanity would eventually become a core element of Marvel Universe continuity. Kirby’s other Marvel creations in this period include Devil Dinosaur, Machine Man, and an adaptation and expansion of the movie 2001: A Space Odyssey, as well as an abortive attempt to do the same for the classic television series, The Prisoner. He also wrote and drew Black Panther and drew numerous covers across the line.

Still dissatisfied with Marvel’s treatment of him, and with the company’s refusal to provide health and other employment benefits, Kirby left Marvel to work in animation. In that field, he did designs for Turbo Teen,Thundarr the Barbarian and other animated television series. He also worked on The Fantastic Four cartoon show, reuniting him with scriptwriter Stan Lee. He illustrated an adaptation of the Walt Disney movie The Black Hole for Walt Disney’s Treasury of Classic Tales syndicated comic strip in 1979-80.

In 1979, Kirby drew concept art for film producer Barry Geller’s script treatment adapting Roger Zelazny’s science fiction novel, Lord of Light, for which Geller had purchased the rights. In collaboration, Geller commissioned Kirby to draw set designs that would also be used as architectural renderings for a Colorado theme park to be called Science Fiction Land; Geller announced his plans at a November press conference attended by Kirby, former NFL American football star Rosey Grier, writer Ray Bradbury, and others. While the film did not come to fruition, Kirby’s drawings were used for the CIA’s “Canadian caper”, in which some members of the U.S. embassy in Tehran, Iran, who had avoided capture in the Iran hostage crisis, were able to escape the country posing as members of a movie location-scouting crew.

In the early 1980s, Pacific Comics, a new, non-newsstand comic book publisher, made a then-groundbreaking deal with Kirby to publish a creator-owned series, Captain Victory and the Galactic Rangers, and the six-issue miniseries Silver Star, which was collected in hardcover format in 2007. This, together with similar actions by other independent comics publishers as Eclipse Comics (where Kirby co-created Destroyer Duck in a benefit comic-book series published to help Steve Gerber fight a legal case versus Marvel), helped establish a precedent to end the monopoly of the work for hire system, wherein comics creators, even freelancers, had owned no rights to characters they created.

Though estranged from Marvel, Kirby continued to do periodic work for DC Comics during the 1980s, including a brief revival of his “Fourth World” saga in the 1984 and 1985 Super Powers miniseries and the 1985 graphic novel The Hunger Dogs. In 1987, under pressure from comics creators and the fan community, Marvel finally returned approximately 1,900 or 2,100 pages of the estimated 10,000 to 13,000 Kirby drew for the company.

Kirby also retained ownership of characters used by Topps Comics beginning in 1993, for a set of series in what the company dubbed “The Kirbyverse”.These titles were derived mainly from designs and concepts that Kirby had kept in his files, some intended initially for the by-then-defunct Pacific Comics, and then licensed to Topps for what would become the “Jack Kirby’s Secret City Saga” mythos. Marvel posthumously published a “lost” Kirby/Lee Fantastic Four story, Fantastic Four: The Lost Adventure (April 2008), with unused pages Kirby had originally drawn for a story that was partially published in Fantastic Four #108 (March 1971).

On February 6, 1994, Kirby died at age 76 of heart failure in his Thousand Oaks, California home. He was buried at the Pierce Brothers Valley Oaks Memorial Park, Westlake Village, California.

Born

- August, 28, 1917

- USA

- New York City, New York

Died

- February, 06, 1994

- USA

- Thousand Oaks, CA

Cemetery

- Pierce Brothers Valley Oaks Memorial Park

- Westlake Village, California

- USA