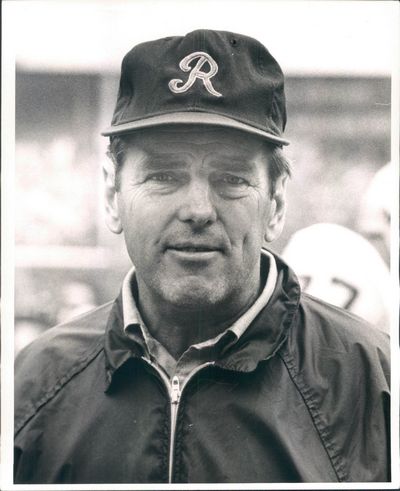

George Allen (George Allen)

George Allen

Allen was born in Nelson County, Virginia, the son of Loretta M. and Earl Raymond Allen, who was recorded in the 1920 and 1930 U.S. census records for Wayne County, Michigan as working as a chauffeur to a private family. He earned varsity letters in football, track and basketball at Lake Shore High School in St. Clair Shores, Michigan. Allen went to Alma College and later at Marquette University, where he was sent as an officer trainee in the U. S. Navy’s World War II V-12 program. He graduated with a B.S. in education from Eastern Michigan University. He attended the University of Michigan where he earned his M.S. in Physical Education in 1947. Coach Allen was the head college football coach for the Morningside Mustangs located in Sioux City, Iowa. The Morningside team was called the Chiefs at that time. He held that position for 3 seasons, from 1948 until 1950. His coaching record at Morningside was 16 wins, 11 losses and 2 ties. As of the conclusion of the 2009 season, this ranks him #5 at Morningside in total wins and #5 at the school in winning percentage (.586). From 1951 through 1956, he coached Whittier College in California where he put together a 32–22–5 mark.

Allen joined the Los Angeles Rams staff in 1957, coaching under fellow Hall of Fame coach Sid Gillman. Allen was dismissed after one season, and after several months residing in Los Angeles out of football, he was brought to Chicago during the 1958 season by George Halas, founding owner and head coach of the Chicago Bears. The original purpose of Allen’s hiring was to scout the Rams, whom the Bears would play twice during the season; Allen was asked for insights into Gillman’s, and the Rams’, offensive strategy and signals. Allen’s thoroughness and attention to detail so impressed Halas that he eventually earned a full-time position on the coaching staff, and during the latter stages of the 1962 season Allen was given the responsibility of what is now known as “defensive coordinator,” replacing veteran Clark Shaughnessy. His defensive schemes and tactics—and his strong motivational skills—helped make the Bears’ unit one of the stingiest of its era. Allen’s presence also had a formative effect on such future Hall of Fame players as linebacker Bill George and end Doug Atkins during their most productive years. By 1963, in his first full season as coordinator, Allen’s innovative defensive strategies helped the Bears yield a league-low 144 total points, 62 fewer than any other team, and earn an 11-1-2 record that sent them to the 1963 NFL Championship. Following their 14-10 victory over the New York Giants on December 29 at frigid Wrigley Field, the Bears’ players awarded Allen the honor of the “game ball.” NBC’s post-game locker-room television coverage infamously captured Bears players singing “Hooray for George, Hooray at last; Hooray for George, He’s a Horse’s ass!”

Allen was also given responsibility for the Bears’ college player drafts; most likely his best-remembered choices were three players who won election the to the NFL Hall of Fame and became household names in American sport—end Mike Ditka (chosen in 1961), halfback Gale Sayers and middle linebacker Dick Butkus (1965). Allen’s was the most common name to be suggested as a replacement for Halas should the grand old man of the league decide to step down. Jeff Davis’s biography “Papa Bear” states that Halas informally told Allen in 1964 and 1965 that he would ultimately name him as head coach. But in 1965, after a 9-5 Bears finish that earned the iron-willed Halas NFL Coach of the Year honors, Allen decided to look elsewhere to fulfill his head-coaching ambitions.

At the end of the 1965 season, Allen reached an agreement with owner Dan Reeves of the Los Angeles Rams to replace Harland Svare as head coach. He quickly faced a legal battle with Halas, who claimed that Allen’s leaving was in breach of his Bears contract. (Halas accused Allen and the Rams of “chicanery.”) The Bears’ owner did win his case in a Chicago court but immediately allowed Allen to leave, saying he initiated the lawsuit to make a point about the validity of contracts. Halas would not be so magnanimous in an NFL meeting soon after when he attacked Allen’s character. Upon hearing this, Green Bay coach Vince Lombardi joked to Reeves, “Sounds like you’ve got yourself a hell of a coach.”

The Rams had for some time been dwelling in or just above the NFL’s basement. The team boasted considerable talent at several positions, most notably on the defensive line; the “Fearsome Foursome” (David Deacon Jones, Merlin Olsen, Rosey Grier, and Lamar Lundy) had gained vast attention on a losing team. Allen brought his well-known motivational skills to Los Angeles, and his twice-daily rigorous training-camp practices took players by surprise. He revealed the philosophy that he would be known for throughout his NFL career—acquiring veteran players for draft picks to fill specific roles. His motto was “the future is now.” He also emphasized the role of special teams (kickoff, punt, and field-goal units) as integral to team success. He revamped the Rams’ secondary with trades and installed quarterback Roman Gabriel, previously relegated to the bench, as his starter. Allen vaulted the Rams from a 4-10 record in 1965 to 8-6 in his first year–the team’s first winning season since 1958. Allen received 1967 Coach of the Year honors for leading the Rams to an 11-1-2 record and the NFL Coastal Division title, their first post-season berth since 1955. After the Rams finished an injury-plagued 1968 season with a 10-3-1 mark, Allen was fired; the news surprised the football world, but subsequent reports revealed that discord between Reeves and Allen had been growing for some time. By some accounts, the owner’s lower-key temperament differed from Allen’s intense approach; more importantly, some animus had developed between the two men in November 1968. After the favored Rams struggled to a tie at San Francisco, Allen disparaged the sloppy Kezar Stadium turf; a few days later Reeves, addressing reporters, subtly admonished his coach for making what he considered an “alibi.” The next week, after a narrow home win over the New York Giants, Allen rebuffed Reeves’s handshake and upbraided him for “embarrassing me and my family.”

It might have been expected that Allen’s firing met with criticism by fans and reporters, but what was not anticipated was the Ram players’ reaction; thirty-eight members of the team’s forty-man roster, including such standouts as Gabriel, Jones, Olsen, Lundy, Dick Bass, Jack Snow, Bernie Casey, Tom Mack, Irv Cross, Ed Meador, and Jack Pardee, stated for the record that they would seek a trade or retire if Allen were not reinstated. Many of these players convened a press conference at a Los Angeles hotel to urge their employer, Reeves, to reconsider his decision. Allen, wearing dark glasses, spoke briefly to thank his players for their support but did not make an appeal for his job. After some negotiation Reeves offered Allen a new two-year contract, although there was no indication that the two men had reconciled their differences.

Allen and the 1969 Rams seemed to justify the coach’s renewed presence; the Rams’ 11-3 mark earned them a Coastal Division title as Gabriel won the NFL’s Most Valuable Player award. But in both 1969 and 1970 Allen’s team could not produce the championship that many had predicted for them. At the end of 1970, with the Rams missing the playoffs and Allen’s contract expiring, Reeves dismissed the coach again. It had been tacitly assumed that Allen had been granted the two extra years to bring the Rams a title, and so the second time the firing met with neither fan outrage nor player objection. Allen quietly left Los Angeles as the most successful coach in Rams history. He was replaced by UCLA coach Tommy Prothro, almost Allen’s opposite in personality and approach.

Allen was much sought after as soon as he parted ways with the Rams, and he agreed to terms with Redskins majority owner Edward Bennett Williams. Replacing interim coach Bill Austin, who had succeeded Vince Lombardi after his death in 1970, Allen demanded (and got) full authority over player personnel decisions, as Lombardi had had. Shortly after joining the Redskins Allen began remaking the roster to his liking; he made a series of trades with his former Ram team and brought seven 1970 Los Angeles players to Washington, including the starting linebacker corps (Maxie Baughan, Myron Pottios, and Pardee). Sportswriters nicknamed the team the “Ramskins” or the “Redrams.” Allen continued his practice of bringing in veteran players at all positions; one was quarterback Bill Kilmer, something of an NFL journeyman for a decade, whose wobbly but efficient passing and raw-boned leadership complemented and eventually supplanted strong-armed veteran Sonny Jurgensen. Allen restored the Redskins to competitiveness after over two decades of losing. The 1971 team was undefeated through late October and finished with a surprising 9-4-1 record and its first trip to the playoffs since 1945. Perhaps Allen’s most satisfying 1971 victory was a December Monday-night win in Los Angeles that not only clinched the NFC East title, but also all but ended the Rams’ playoff hopes.

Allen’s 1972 team, with Kilmer by now the starting quarterback, won the NFC East title with an 11-3 record; the defense allowed a conference-low 218 points on the way to a NFC title, which was secured with a 26-3 home victory over the Dallas Cowboys. The Redskins gained the chance to contest the undefeated Miami Dolphins for the world championship, a team they had beaten in the pre-season, but in Super Bowl VII at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum, the “‘Skins” were overmatched by the Dolphins’ relentless running game and staunch defense, losing 14-7.

With Allen’s painstaking attention to detail and enthusiastic approach, Washington’s teams were known for their spirited play and camaraderie, with the coach often leading a chant of “Three Cheers for the Redskins” (“Hip Hip Hooray”) in the locker room after wins. The Redskins acquired a reputation of a team that came by its success through hard work and workmanlike play that was rarely reflected in individual statistics. Becoming a household phrase among NFL fans was the “Over-the-Hill Gang”–the aging Redskin veterans who seemed to save their best efforts for the most important games. They reached the playoffs in five of Allen’s seven years, but were not able to duplicate their 1972 Super Bowl trip. It was during this time that the Redskins’ fierce rivalry with the Dallas Cowboys became a choice subject for pro football fans, and Allen inflamed it with bizarre actions like taunting Cowboys players while wearing an Indian headdress.

As had been the case with the Rams, Allen’s intense approach was seen to indicate that winning in the present was all-important, with planning for the franchise’s future taking a lesser priority. In 1977 the Redskins failed to reach the postseason for the second time in three seasons, and although owner Williams did attempt to negotiate a new pact for Allen, there were rumors that he was beginning to question his coach’s philosophy.

After rejecting a $1 million, four-year contract offer throughout the 1977 season, Allen was dismissed by the Redskins after the 1977 season. Allen was replaced by one of his favorite players, Jack Pardee, by then the promising young head coach of the Bears. In February 1978 Rams owner Carroll Rosenbloom was searching for a new coach after parting ways with Chuck Knox. Allen returned to Los Angeles with much media fanfare. His second stint as the Rams’ head coach was an unfortunate experience for all concerned. Allen did not have full authority over personnel and thus worked with general manager Don Klosterman to oversee a talented roster that had made the team a perennial playoff challenger. Allen brought with him his scrupulous discipline and attention to detail, which extended to practice-field protocol and dining-hall decorum. Almost immediately a group of Ram players chafed at the regulations, and some made their grievances public. A few, including standout linebacker Isiah Robertson, briefly left camp. As newspaper reports were quoting players expressing confidence that differences would be resolved, the Rams played listlessly and lost the first two games of the 1978 exhibition schedule. Rosenbloom decided that for the season to be salvaged a change must be made, and the announcement of Allen’s abrupt dismissal was made on August 13. Many of Allen’s own players were surprised by the decision. Defensive coordinator Ray Malavasi, well-respected and liked by players (and the only holdover from Chuck Knox’ staff), replaced him; the Rams ultimately advanced to that year’s NFC Championship Game. Allen soon joined CBS Sports as an analyst for NFL network telecasts, and worked in the broadcast booth from 1977 to 1983. He, with former Cleveland Browns great running back Jim Brown and play-by-play announcer Vin Scully, made up the network’s only three-man announcing team.

George Halas biographer Jeff Davis notes that Allen had contacted Halas in late 1981, asking to be considered for the vacant head coaching position with the Bears. Halas angrily rejected Allen’s overtures and hired his old friend and former player Mike Ditka instead. Allen had a brief flirtation with the Canadian Football League when he was hired by the Montreal Alouettes as president and chief operating manager on February 19, 1982. Allen also agreed to purchase 20 percent of the team, with an option to become the majority shareholder. However, three months later, Allen resigned after continued financial troubles and a shift in majority ownership from Nelson Skalbania to Harry Ornest soured Allen on the situation.

On June 21 of that same year, Allen became head coach and general manager of the Chicago Blitz of the fledgling United States Football League, returning to the city where he had established his NFL coaching credentials two decades earlier. In his first season in 1983, the Blitz were tabbed as the early favorite to capture the league’s inaugural title. The team finished in a tie for first with the Michigan Panthers with a 12-6 record, but lost the tiebreaker that made them the wild card team. In their playoff game against the Philadelphia Stars, the Blitz held a commanding 38-17 lead before a late comeback sent the game into overtime, where Chicago lost by a 44-38 score.

Two months after that collapse, the Blitz were part of a bizarre transaction in which the entire franchise was essentially traded for the Arizona Wranglers, with the two teams switching cities. During that 1984 season, Allen’s Wranglers struggled early before finishing with a 10-6 mark, earning another wild card spot. In the opening round of the playoffs, Arizona staged a comeback to knock off the Houston Gamblers, 17-16. The following week, the Wranglers stopped the Los Angeles Express, 35-23, in the Western Conference final. However, the run of success came to an end in the USFL Championship Game, when Arizona was shut down in a 23-3 defeat. In September 1984, Allen resigned his positions with the team after the Wranglers’ financial troubles necessitated in severe budget cuts. Following several years out of the public eye, he accepted a one-year offer to coach at Long Beach State University.

Allen was considered one of the hardest working coaches in football. He is credited by some with popularizing the coaching trend of 16-hour (or longer) work-days. He sometimes slept at the Redskin Park complex he designed. Allen’s need for full organizational control and his wild spending habits would create friction between him and the team owners he worked for. Edward Bennett Williams, the Redskins’ president, once famously said, “George was given an unlimited budget and he exceeded it.” In ending Allen’s second stint as the Rams’ head coach after only two preseason games in 1978, Carroll Rosenbloom said, “I made a serious error of judgment in believing George could work within our framework.” and “He got unlimited authority and exceeded it.” Allen was also notorious for his paranoia, regularly believing that his practices were being spied upon and that his offices were bugged. He even went as far as being the first coach in the NFL to employ a full-time security man, Ed Boynton, to keep potential spies away and patrol the woods outside Redskin Park. As documented by NFL Films, Allen was known to eat ice cream or peanut butter for many meals because it was easy to eat, and saved time so Allen could get back to preparing for the next game. Allen kept in shape as a coach, and would run several miles at the start of each day. He did not curse, smoke, or drink, instead habitually consuming milk (some suspected that this beverage of choice arose from ulcers they suspected the always-high strung coach to suffer from). Coach Allen would later be appointed by President Ronald Reagan to the President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports. It’s interesting to note President Richard Nixon (an armchair coach) once “recommended” the team run an end-around play by wide receiver Roy Jefferson. Allen agreed, choosing to run the play against the San Francisco 49ers in the 1971 NFC Divisional playoff game. Jefferson was tackled by the 49ers’ Cedrick Hardman for a 13-yard loss on the play, a game the Redskins ended up losing.

As a coach, Allen was known for his tendency to prefer veteran players to rookies and younger players. During Allen’s early years with the Redskins, the team was known as the “Over the Hill Gang,” due to the predominance of players over the age of 30, such as quarterback Billy Kilmer. Upon becoming Redskins coach, Allen traded for or acquired many players – all veterans of course – he had formerly coached with the Rams, including Jack Pardee, Richie Petitbon, Myron Pottios, John Wilbur, George Burman, and Diron Talbert, leading to the Redskins sometimes being referred to in those days as the “Ramskins.” The phrase “the future is now” is often associated with Allen. Allen made 131 trades as an NFL coach, 81 of which came during the seven years he was coach of the Redskins.

Allen was also known for emphasizing special teams play, and is credited with being the NFL’s second coach to hire a special teams coach (Jerry Williams was the first in 1969) to focus exclusively on the play of that unit when he took over the Washington Redskins in the early ’70’s. His first special teams coach, Dick Vermeil, would later win a Super Bowl as head coach of the St. Louis Rams. His second special teams coach, Marv Levy, would lead the Buffalo Bills to four consecutive Super Bowl appearances. Marv Levy came to his staff after being the first special teams coach in the NFL having been hired by Philadelphia Eagles coach Jerry Williams in 1969.

Allen had the third best winning percentage in the NFL (.681), exceeded only by Vince Lombardi (.736) and John Madden (.731). He also never coached a team to a losing season. This was particularly notable in the case of the Redskins, who had only finished above .500 once over the past 15 seasons (1969, under Lombardi) before Allen’s arrival. He was noted primarily as a defensive innovator, and as a motivator. Allen was an early innovator in the use of sophisticated playbooks, well-organized drafts, use of special teams and daring trades for veterans over new players. He is also known for sparking the Dallas Cowboys/Washington Redskins rivalry. He was 7–8 against the Cowboys in his career. He was inducted to the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 2002.

Allen married the former Henrietta (Etty) Lumbroso, with whom he had four children, three sons and one daughter. His son George is a Republican politician, having served as Governor and U.S. Senator from Virginia. His son Bruce is the current general manager of the Washington Redskins and was a former general manager of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers of the National Football League and also a former member of the front office of the Oakland Raiders. Gregory Allen is a sports psychologist. Allen’s daughter Jennifer, a correspondent for the NFL Network, wrote a book about her relationship with her father titled The Fifth Quarter which outlined the man’s icy demeanor toward his family, and his obsession with football to the exclusion of all else.

Allen’s death may have been indirectly caused by a Gatorade shower. He died on December 31, 1990, from ventricular fibrillation in his home in Palos Verdes Estates, California, at the age of 72. Shortly before his death, Allen noted that he had not been feeling well since some of his Long Beach State players dumped a Gatorade bucket filled with ice water on him following a season-ending victory over the University of Nevada, Las Vegas on November 17, 1990 (he remarked that the university couldn’t afford actual Gatorade).

The sports editor of the Long Beach State newspaper, the Daily Forty-Niner, was on the field that day and recalled that the temperature was in the 50s with a biting wind. Allen stayed on the field for media interviews for quite a while in his drenched clothing, and boarded the bus back to Long Beach State soaking wet. However, he had promised a winning season to a football program on the verge of collapse, and in his final game delivered on his promise. His players gleefully hoisted him on their shoulders as photographers snapped away, and Allen went out a winner. Allen said his season at Long Beach State was the most rewarding of his entire career.

Allen’s son George denied that the Gatorade shower caused the death, attributing it to an existing heart arrythmia. He stated that seeing Gatorade showers on television was a reminder that his father “went out a winner”. After Allen’s death, the soccer and multipurpose field area on the lower end of campus was dedicated in his honor as George Allen Field. A youth baseball field in Palos Verdes Estates is also named after him.

Born

- April, 29, 1918

- Nelson County, Virginia

Died

- December, 31, 1990

- Rancho Palos Verdes, California

Cemetery

- Green Hills Memorial Park

- Rancho Palos Verdes, California