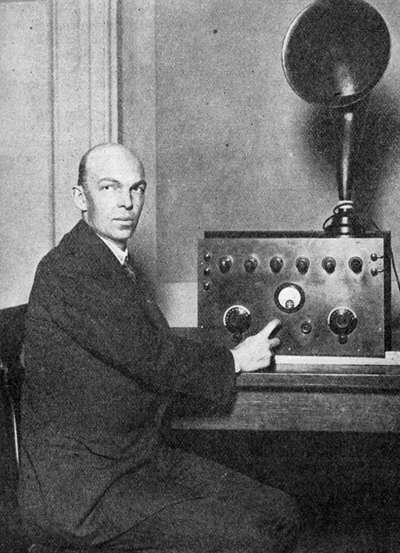

Edwin Howard Armstrong (Edwin Howard Armstrong)

Armstrong was born in the Chelsea district of New York City to John and Emily Armstrong. His father was the American representative of the Oxford University Press, which published Bibles and standard classical works. John Armstrong, who was also a native of New York, began working at the Oxford University Press at a young age and eventually reached the position of Vice President of the American branch. Emily Smith first met John Armstrong in the North Presbyterian Church, which was located at 31st Street and Ninth Avenue. Emily Smith had strong family ties to Chelsea, which centered around the church, in which her family took an active role.

When the church moved further North the Smith and Armstrong families followed it. In 1895 the Armstrong family moved from their brownstone row house at 347 West 29th Street to another similar house at 26 West 97th Street in the Upper West Side.[6] At the age of eight Armstrong contracted a disease that was known as St. Vitus’ Dance, which left him with a lifelong tic when excited or under stress. Because of the illness Armstrong was withdrawn from school for two years. In order to improve his health the Armstrong family moved in 1902 from the Upper West Side into a house at 1032 Warburton Avenue in Yonkers, which overlooked the Hudson river. The Smith family moved into a house next door. Armstrong’s physical tic and the years he was removed from school led him to become withdrawn. Armstrong showed an interest in electrical and mechanical devices, particularly trains, from an early age. He loved heights and constructed a makeshift radio antenna tower in his back yard. Swinging on a bosun’s chair, he would hoist himself up and down the tower to the concern of his neighbors.

In late 1917, Armstrong was invited to join the U.S. Army Signal Corps with the rank of captain and was sent to Paris to help set up a wireless communication system for the Army. He returned to the United States in the fall of 1919. During his service in both world wars, Armstrong gave the U.S. military free use of his patents. Use of these was critical to the Allied victories. Unlike many engineers, Armstrong was never a corporate employee. He performed research and development by himself and owned his patents outright. He did not subscribe to conventional wisdom and was quick to question the opinions of his professors and his peers.

As an undergraduate, and later as a professor at Columbia University, Armstrong worked from his parent’s attic in Yonkers, New York, to develop the regenerative circuit, the superheterodyne receiver, and the superregenerative circuit. He studied under Professor Mihajlo Pupin at the Hartley Laboratories, a separate research unit at Columbia University. Thirty-one years after graduating from Columbia he became Professor of Electrical Engineering, filling the vacancy left by the death of Professor J. H. Morecroft. He held the position until his death.

Armstrong contributed the most to modern electronics technology. His discoveries revolutionized electronic communications. Regeneration, or amplification via positive feedback is still in use to this day. Also, Armstrong discovered that Lee De Forest’s Audion would go into oscillation when feedback was increased. Thus, the Audion could not only detect and amplify radio signals, it could transmit them as well.

While De Forest’s addition of a third element to the Audion (the grid) and the subsequent move to modulated (voice) radio is not disputed, De Forest did not put his device to work. Armstrong’s research and experimentation with the Audion moved radio reception beyond the crystal set and spark-gap transmitters. Radio signals could be amplified via regeneration to the point of human hearing without a headset. Armstrong later published a paper detailing how the Audion worked, something De Forest could not do. De Forest did not understand the workings of his Audion.

Armstrong’s service as a signal officer in World War I led to his design of the superheterodyne circuit. The discovery and development of the technology made radio receivers, then the primary communications devices of the time, more sensitive and selective. Before heterodyning, radio signals often overrode and interfered with each other. Heterodyning also made radio receivers much easier to use, rendering obsolete the multitude of tuning controls on radio sets of the time. The superheterodyne technology is still used today. There was a dispute regarding who invented superheterodyne radio. Walter Schottky claimed that he had independently invented super heterodyne radio.

Even as the regenerative-circuit lawsuit continued, Armstrong was working on another momentous invention. Working in the basement laboratory of Columbia’s Philosophy Hall, he invented wide-band frequency modulation (FM) radio. Rather than varying (“modulating”) the amplitude of a radio wave to encode an audio signal, the new method varied the frequency. FM enabled the transmission and reception of a wider range of audio frequencies, as well as audio free of “static”, a common problem in AM radio. (Armstrong received a patent on wide-band FM on December 26, 1933.)

In 1922, John Renshaw Carson of AT&T, inventor of Single-sideband modulation (SSB modulation), had published a paper in the Proceedings of the IRE arguing that FM did not appear to offer any particular advantage. Armstrong managed to demonstrate the advantages of FM radio despite Carson’s skepticism in a now-famous paper on FM in the Proceedings of the IRE in 1936, which was reprinted in the August 1984 issue of Proceedings of the IEEE.

Today the consensus regarding FM is that narrow band FM is not so advantageous in terms of noise reduction, but wide band FM can bring great improvement in signal to noise ratio if the signal is stronger than a certain threshold. Hence Carson was not entirely wrong, and the Carson bandwidth rule for FM is still important today. Thus, both Carson and Armstrong ultimately contributed significantly to the science and technology of radio. The threshold concept was discussed by Murray G. Crosby (inventor of Crosby system for FM Stereo) who pointed out that for wide band FM to provide better signal to noise ratio, the signal should be above a certain threshold, according to his paper published in Proceedings of the IRE in 1937. Thus Crosby’s work supplemented Armstrong’s paper in 1936.

In 1934 Armstrong began working for RCA at the request of the president of RCA, David Sarnoff. Sarnoff and Armstrong first met at a boxing match involving Jack Dempsey in 1920. At the time Sarnoff was a young executive with an interest in new technologies, including radio broadcasting. In the early 1920s Armstrong drove off with Sarnoff’s secretary, Marion MacInnes, in a French sports car. Armstrong and MacInnes were married in 1923. While Sarnoff was understandably impressed with Armstrong’s FM system, he also understood that it was not compatible with his own AM empire. Sarnoff came to regard FM as a threat and refused to support it any further.

From May 1934 until October 1935, Armstrong conducted the first large scale field tests of his FM radio technology from a laboratory constructed by RCA on the 85th floor of the Empire State Building. An antenna attached to the spire of the building fired radio waves at receivers about 80 miles away. However RCA had its eye on television broadcasting, and chose not to buy the patents for the FM technology. A June 17, 1936, presentation at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) headquarters made headlines nationwide. He played a jazz record over conventional AM radio, then switched to an FM broadcast. “[I]f the audience of 50 engineers had shut their eyes they would have believed the jazz band was in the same room. There were no extraneous sounds,” noted one reporter. He added that several engineers described the invention “as one of the most important radio developments since the first earphone crystal sets were introduced.” In 1937, Armstrong financed construction of the first FM radio station, W2XMN, a 40 kilowatt broadcaster in Alpine, New Jersey. The signal (at 42.8 MHz) could be heard clearly 100 miles (160 km) away, despite the use of less power than an AM radio station.

RCA began to lobby for a change in the law or FCC regulations that would prevent FM radios from becoming dominant. By June 1945, the RCA had pushed the FCC hard on the allocation of electromagnetic frequencies for the fledgling television industry. Although they denied wrongdoing, David Sarnoff and RCA managed to get the FCC to move the FM radio spectrum from 42–50 MHz, to 88–108 MHz, while getting new low-powered community television stations allocated to a new Channel 1 in the 44-50 MHz range. In fairness to the FCC, the 42–50 MHz band was plagued by frequent tropospheric and E-layer stratospheric propagation which caused distant high powered stations to interfere with each other. The problem becomes even more severe on a cyclical basis when sunspot levels reach a maximum every 11 years and lower VHF band signals below 50 MHz can travel across the Atlantic Ocean or from coast to coast within North America on occasion. Sunspot levels were near their cyclical peak when the FCC reallocated FM in 1945. The 88–108 MHz range is a technically better location for FM broadcast because it is less susceptible to this kind of frequent interference. (Channel 1 eventually had to be deleted as well, with all TV broadcasts licensed at frequencies 54 MHz or higher, and the band is no longer widely used for emergency first responders either, those services having moved mostly to UHF.)

But the immediate economic impact of the shift, whatever its technical merit, was devastating to early FM broadcasters. This single FCC action would render all Armstrong-era FM receivers useless within a short time as stations were moved to the new band, while it also protected both RCA’s AM-radio stronghold and that of the other major competing networks, CBS, ABC and Mutual. Armstrong’s radio network did not survive the shift into the high frequencies and was set back by the FCC decision. This change was strongly supported by AT&T, because loss of FM relaying stations forced radio stations to buy wired links from AT&T.

Furthermore, RCA also claimed invention of FM radio and won its own patent on the technology. A patent fight between RCA and Armstrong ensued. RCA’s momentous victory in the courts left Armstrong unable to claim royalties on any FM receivers, including televisions, which were sold in the United States. The undermining of the Yankee Network and his costly legal battles brought ruin to Armstrong, by then almost penniless and emotionally distraught. Eventually, after Armstrong’s death, many of the lawsuits were decided or settled in his favor, greatly enriching his estate and heirs. But the decisions came too late for Armstrong himself to enjoy his legal vindication.

Armstrong married Sarnoff’s secretary, Marion McInnis, in December 1922. He gave Marion the world’s first portable radio as a wedding gift. Armstrong bought a Hispano-Suiza motor car before the wedding, which they drove to Palm Beach, Florida for their honeymoon. He kept the car until his death. McInnis, who was born in 1898, was survived by two nephews and a niece after her death in 1979. He was an avid tennis player until an injury in 1940, and drank an Old Fashioned with dinner.

Financially broken and mentally beaten after years of legal tussles with RCA and others, Armstrong lashed out at his wife one day with a fireplace poker, striking her on the arm. MacInnis left their apartment to stay with her sister, Marjorie Tuttle, in Granby, Connecticut.

On January 31, 1954 Armstrong removed the air conditioner from the window and jumped to his death from the thirteenth floor of his New York City apartment. His body was found fully clothed, with a hat, overcoat and gloves, the next morning by a River House employee on a third-floor balcony. The New York Times described the contents of his two-page suicide note to his wife: “he was heartbroken at being unable to see her once again, and expressing deep regret at having hurt her, the dearest thing in his life.” The note concluded, “God keep you and Lord have mercy on my Soul.” After his death, a friend of Armstrong estimated that 90 percent of his time was spent on litigation against RCA. Upon hearing the news, David Sarnoff supposedly remarked, “I did not kill Armstrong.”

MacInnis was able to formally establish Armstrong as the inventor of FM following protracted court proceedings over five of his basic FM patents. Until her death in 1979 she participated in the Armstrong Memorial Research Foundation that she founded. Edwin Armstrong was buried in Locust Grove Cemetery, Merrimac, Massachusetts.

Born

- December, 18, 1890

- USA

- Chelsea, New York City, New York

Died

- January, 31, 1954

- USA

- New York City, New York

Cemetery

- Locust Grove Cemetery

- Merrimac, Massachusetts

- USA