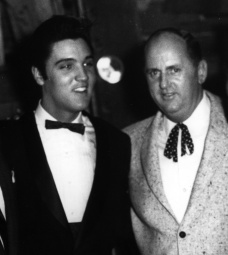

Colonel Tom Parker (Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk)

Colonel Tom Parker

Not to get all Joseph Campbell-ish here, but as we look at the figures who populate postmodern American myth—that pantheon of movie stars, musicians, artists, and politicians we have consensually elevated to demi-godhood—we see a number of recurring motifs. The American myth-figure comes from a humble background, receives a stroke of extreme good fortune, creates a number of defining moments, burns out young, and dies tragically, robbing the world of what would surely have been his or her finest work. This last motif, the masterpiece that will forever be unrealized, is the glue that holds the whole motif-complex together: the “if-only” factor. If only Jim Morrison hadn’t ODed he’d have become our greatest poet. If only Marilyn Monroe had been taken seriously as an actress, she would have realized the promise she showed in her last film, The Misfits. If only Kennedy hadn’t gone to Dallas, or James Dean hadn’t the need for speed, or Kurt Cobain hadn’t eaten the shotgun . . .

The life and times of Elvis Presley contain a barrage of if-onlies, as befits perhaps the largest of our latter-day myths. Fans and scholars of the King will forever argue the effects of the often bizarre curves in his career—whether going into the Army helped or hurt him, whether the movies gave him longevity or consigned him to mediocrity, whether his drug use and profligate spending were the result of deep depression or the compulsive behavior of the child of white trash suddenly become nouveau riche. One thing, however, meets with general agreement: whatever Elvis’s other problems may have been, his biggest failing was his utter dependence upon his manager, Colonel Tom Parker. When they inked their first contract, Parker took an unusual 25% commission; by the time of the King’s death, three-fourths of Elvis’s income went into Parker’s pocket, seemingly without Elvis’s knowledge. If Elvis was Faust, selling his soul for the riches of the earth, Parker will always be Mephistopheles, paying with a mess of pottage.

And like Mephistopheles, Parker is a mystery. He was born Andreas van Kuijk, a Dutch immigrant who changed his name the moment he stepped off the boat in Tampa Bay harbor but never applied for a green card. He worked as a carny for Royal Amusement Shows. He briefly managed the careers of country legends Eddy Arnold and Hank Snow. He was a friend of country star and twice Louisiana Governor Jimmie Davis (“You Are My Sunshine”), who bestowed the honorary rank of Colonel upon him in exchange for services rendered during Davis’s campaign. And of course he managed Elvis Presley for virtually the singer’s entire career. But that is pretty much all we know about the man, despite his tight relationship with the world’s most famous client.

Tennessee historian and biographer James L. Dickerson makes a valiant attempt to change that in his book Colonel Tom Parker: The Curious Life of Elvis Presley’s Eccentric Manager, but he never really succeeds. Dickerson talked with dozens of people who were acquainted with Parker and dug up a great many documents pertaining in one way or another to him, but whereas most people who wish to hide their secrets bury the evidence, Parker simply worked it so that evidence never existed in the first place. Without birth records, registration papers, marriage certificate, military records, or even (apparently) close friends, it’s next to impossible to get a handle on the man. Dickerson thus resorts to a great deal of speculation and virtual lunges at conclusions. For example, Dickerson’s explanation for the reason Parker was not drafted during World War II runs roughly along these lines: Parker’s draft rating indicated someone who was either physically or “morally” unfit; Parker could not possibly have been physically unfit, as he lived for another 58 years, so the reason for his failure to pass muster had to be on moral grounds; at that time, the “turn-your-head-and-cough” test was used not only to detect hernias but also to filter out any draftee who got an erection; if the healthy Parker failed the physical, it could only be because a certain part of his body stood up and saluted the doctor.

Even if we ignore the other glaring logical fallacies in the preceding argument, we cannot ignore the primary problem: it’s all rank conjecture, based upon a single possibility among infinite others in the vacuum of real evidence. For all Dickerson knows, Parker could have paid off the doctor, or actually had a hernia (I hear they’re non-lethal), or even used the Jedi mind trick. This kind of blind extrapolation runs throughout the book, as Dickerson takes the handful of things he knows about Parker—he was an illegal immigrant, he was a carny, he had a gambling problem—and attempts to fit all of the other questions surrounding him and his relationship with Elvis into a decidedly Procrustean bed. The reason why Elvis never toured outside the U.S. is the same reason why he always overpaid his taxes—because Parker wanted to avoid government background checks. The reason why Elvis enlisted in the Army ahead of the draft is the same reason he fired his original band—because Parker the old carny wanted to keep Elvis isolated from anyone who might convince his prize attraction that he could get a better deal with another manager. Dickerson manages to hang every unanswered question about Elvis’s career, from a missing footstone on Gladys Presley’s grave to Elvis’s failure to grow as an actor, squarely around Parker’s neck. Like Schroedinger’s experiment with the cat, even contradicting possibilities are equally true in the lack of empirical evidence.

As for the evidence that Dickerson does have, much of it is severely tainted, relying as it does on the testimony of people with assorted axes to grind. Scotty Moore, Elvis’s original guitar player and the subject of an earlier biography by Dickerson, provides a lot of the insights here, but he is hardly an objective source, blaming Parker for drawing up a number of bad contracts that relegated him to mere session-player status. Other testimony comes from Elvis’s ex-wife Priscilla Presley, who discovered after the King’s death that the Presley estate was deeply in the red and blamed Parker’s insanely unfair cut of Elvis’s earnings. Still more evidence is provided by people who either felt cheated by Parker, just plain didn’t like him, or met him once. Conspicuously absent is any word from people who actually knew Parker, resulting in a two-dimensional portrait of a cigar-chomping Disney villain with the ethics of a hyena and the powers of Rasputin. This is not to say that Parker has been misrepresented or abused. He could very well have been the low-rent Machiavelli he is depicted as. We just don’t know, and Dickerson fails to convince us that he knows any more than we do.

What is even more disturbing, however, is that the oversimplification of Colonel Tom Parker leads inevitably to the oversimplification of Elvis Presley. To Dickerson’s credit, this is always Parker’s biography, the well-trod ground of Elvis’s life given just enough ink to clarify Dickerson’s points about Parker, but the fact remains that if Parker is a cartoonish villain, then Elvis is someone who was taken in by a cartoonish villain—he becomes Johnny Bravo. Meanwhile, the biggest questions, the ones this biography should have been able to address, remain unanswered. Why was Elvis never aware of just how much money Parker was taking out of his pocket? Why, when Elvis was constantly surrounded by people because he hated to be alone, was no one ever able to make the case for tax shelters to him? Why did Elvis accept the Colonel’s continual quashing of his acting and musical ambitions? Why in all the vastness of the Presley money-making machine did so much power remain in the hands of one man with so obviously little regard for Elvis? What was the mysterious power the Colonel had over him? There has to be more to this—it’s just too hard to accept the idea that, with all the money, fame, power, and attendant tragedy, in the end the Elvis myth hinges entirely on the fact that the King of Rock and Roll was either a spineless neurotic or a grade-A doofus.

But accept it we must, until someone is able to undertake a deeper exploration of Colonel Tom Parker than Dickerson has. Given the elusive, shadowy nature of Parker’s life, that may be impossible, but as it stands we’re no closer now to answering all the if-onlies than we were before.

Born

- June, 26, 1909

- Breda, Netherlands

Died

- January, 21, 1997

- Las Vegas, Nevada

Cause of Death

- Stroke

Cemetery

- Palm Desert Memorial

- Las Vegas, Nevada