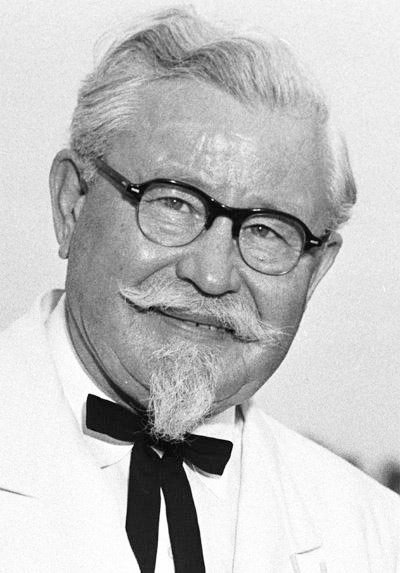

Colonel Sanders (Harland David Sanders)

Sanders was born on September 9, 1890 in a four-room house located 3 miles (5 km) east of Henryville, Indiana. He was the oldest of three children born to Wilbur David and Margaret Ann (née Dunlevy) Sanders. The family attended the Advent Christian Church. The family were of mostly Irish and English ancestry. His father was a mild and affectionate man who worked his 80-acre farm, until he broke his leg after a fall. He then worked as a butcher in Henryville for two years. One summer afternoon in 1895, he came home with a fever and died later that day. Sanders’ mother obtained work in a tomato cannery; and the young Harland was required to look after and cook for his siblings. By the age of seven he was reportedly skilled with bread and vegetables, and improving with meat; the children foraged for food while their mother was away for days at a time for work. When he was 10 Harland began to work as a farmhand for local farmers Charlie Norris and Henry Monk. Sanders’ mother remarried in 1902, and the family moved to Greenwood, Indiana. Sanders had a tumultuous relationship with his stepfather. In 1903 he dropped out of seventh grade (later stating that “algebra’s what drove me off”), and went to live and work on a nearby farm. He then took a job painting horse carriages in Indianapolis. When he was 14 he moved to southern Indiana to work as a farmhand for Sam Wilson for two years. In 1906, with his mother’s approval, he left the area to live with his uncle in New Albany, Indiana. His uncle worked for the streetcar company, and secured Sanders a job as a conductor.

Sanders falsified his date of birth and enlisted in the United States Army in October 1906, completing his service commitment as a teamster in Cuba. He was honorably discharged in February 1907 and moved to Sheffield, Alabama, where an uncle lived. There, he met his brother Clarence who had also moved there in order to escape his stepfather. The uncle worked for the Southern Railroad, and secured Sanders a job there as a blacksmith’s helper in the workshops. After two months, Sanders moved to Jasper, Alabama where he got a job cleaning out the ash pans of trains from the Northern Alabama Railroad (a division of the Southern Railroad) when they had finished their run. Sanders progressed to become a fireman at the age of 16.

In 1909, Sanders found laboring work with the Norfolk and Western Railway. Whilst working on the railroad, he met Josephine King of Jasper, Alabama, and they were married shortly afterwards. They would go on to have a son, Harland, Jr., who died in 1932 from infected tonsils, and two daughters, Margaret Sanders and Mildred Sanders Ruggles. He then found work as a fireman on the Illinois Central Railroad, and he and his family moved to Jackson, Tennessee. By night, Sanders studied law by correspondence through the La Salle Extension University. Sanders lost his job at Illinois after brawling with a work colleague. While Sanders moved to work for the Rock Island Railroad, Josephine and the children went to live with her parents. After a while, Sanders began to practice law in Little Rock for three years, and he earned enough fees for his family to move with him. His legal career ended after he got engaged in a courtroom brawl with his own client. After that, Sanders moved back with his mother in Henryville, and went to work as a laborer on the Pennsylvania Railroad. In 1916, the family moved to Jeffersonville, where Sanders got a job selling life insurance for the Prudential Life Insurance Company. Sanders was eventually fired for insubordination. He moved to Louisville and got a sales job with Mutual Benefit Life of New Jersey.

In 1920, Sanders established a ferry boat company, which operated a boat on the Ohio River between Jeffersonville and Louisville. He canvassed for funding, becoming a minority shareholder himself, and was appointed secretary of the company. The ferry was an instant success. In around 1922 he took a job as secretary at the Chamber of Commerce in Columbus, Indiana. He admitted to not being very good at the job, and resigned after less than a year. Sanders cashed in his ferry boat company shares for $22,000 and used the money to establish a company manufacturing acetylene lamps. The venture failed after Delco introduced an electric lamp that they sold on credit. Sanders moved to Winchester, Kentucky, to work as a salesman for the Michelin Tire Company. He lost his job in 1924 when Michelin closed their New Jersey manufacturing plant. In 1924, by chance, he met the general manager of Standard Oil of Kentucky, who asked him to run a service station in Nicholasville. In 1930, the station closed as a result of the Great Depression.

In 1930, the Shell Oil Company offered Sanders a service station in Corbin, Kentucky rent free, in return for paying them a percentage of sales. Sanders began to serve chicken dishes and other meals such as country ham and steaks. Initially he served the customers in his adjacent living quarters before opening a restaurant. He was commissioned as a Kentucky Colonel in 1935 by Kentucky governor Ruby Laffoon. In July 1939, Sanders acquired a motel in Asheville, North Carolina. His Corbin restaurant and motel was destroyed in a fire in November 1939, and Sanders had it rebuilt as a motel with a 140-seat restaurant. By July 1940, Sanders had finalized his “Secret Recipe” for frying chicken in a pressure fryer that cooked the chicken faster than pan frying. As the United States entered World War II in December 1941, gas was rationed, and as the tourists dried up, Sanders was forced to close his Asheville motel. He went to work as a supervisor in Seattle until the latter part of 1942. He later ran cafeterias for the government at an Ordinance Works in Tennessee, followed by a job as an assistant manager at a cafeteria in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. He left his mistress, Claudia Ledington-Price, as manager of the Corbin restaurant and motel. In 1942, he sold the Asheville business. In 1947, he and Josephine divorced and Sanders married Claudia in 1949, as he had long desired. Sanders was “re-commissioned” as a Kentucky Colonel in 1950 by his friend, Governor Lawrence Wetherby.

In 1952, Sanders franchised “Kentucky Fried Chicken” for the first time, to Pete Harman of South Salt Lake, Utah, the operator of one of that city’s largest restaurants. In the first year of selling the product, restaurant sales more than tripled, with 75% of the increase coming from sales of fried chicken. For Harman, the addition of fried chicken was a way of differentiating his restaurant from competitors; in Utah, a product hailing from Kentucky was unique and evoked imagery of Southern hospitality. Don Anderson, a sign painter hired by Harman, coined the name Kentucky Fried Chicken. After Harman’s success, several other restaurant owners franchised the concept and paid Sanders $0.04 per chicken.

Sanders believed that his Corbin restaurant would remain successful indefinitely, but at age 65 sold it after the new Interstate 75 reduced customer traffic. Left only with his savings and $105 a month from Social Security, Sanders decided to begin to franchise his chicken concept in earnest, and traveled the US looking for suitable restaurants. After closing the Corbin site, Sanders and Claudia opened a new restaurant and company headquarters in Shelbyville in 1959. Often sleeping in the back of his car, Sanders visited restaurants, offered to cook his chicken, and if workers liked it negotiated franchise rights.

Although such visits required much time, eventually potential franchisees began visiting Sanders instead. He ran the company while Claudia mixed and shipped the spices to restaurants. The franchise approach became highly successful; KFC was one of the first fast food chains to expand internationally, opening outlets in Canada and later in England, Mexico and Jamaica by the mid-1960s. The company’s rapid expansion to more than 600 locations became overwhelming for the aging Sanders. In 1964, he sold the Kentucky Fried Chicken corporation for $2 million to a partnership of Kentucky businessmen headed by John Y. Brown, Jr. (a then-29-year-old lawyer and future governor of Kentucky) and Jack C. Massey (a venture capitalist and entrepreneur), and he became a salaried brand ambassador. The initial deal did not include the Canadian operations (which Sanders retained) or the franchising rights in England, Florida, Utah, and Montana (which Sanders had already sold to others). In 1965, Sanders moved to Mississauga, Ontario to oversee his Canadian franchises and continued to collect franchise and appearance fees both in Canada and in the U.S. Sanders bought and lived in a bungalow at 1337 Melton Drive in the Lakeview area of Mississauga from 1965 to 1980. In September 1970 he and his wife were baptized in the Jordan River. He also befriended Billy Graham and Jerry Falwell.

Sanders remained the company’s symbol after selling it, traveling 200,000 miles a year on the company’s behalf and filming many TV commercials and appearances. He retained much influence over executives and franchisees, who respected his culinary expertise and feared what The New Yorker described as “the force and variety of his swearing” when a restaurant or the company varied from what executives described as “the Colonel’s chicken”. One change the company made was to the gravy, which Sanders had bragged was so good that “it’ll make you throw away the durn chicken and just eat the gravy” but which the company simplified to reduce time and cost. Sanders sometimes made surprise visits to KFC restaurants, and if the gravy disappointed him denounced it to the franchisee as “God-damned slop”. In 1973, he sued Heublein Inc.—the then parent company of Kentucky Fried Chicken—over the alleged misuse of his image in promoting products he had not helped develop. In 1975, Heublein Inc. unsuccessfully sued Sanders for libel after he publicly described their gravy as “wallpaper paste” to which “sludge” was added. Sanders and his wife reopened their Shelbyville restaurant as “Claudia Sanders, The Colonel’s Lady” and served KFC-style chicken there as part of a full-service dinner menu, and talked about expanding the restaurant into a chain. He was sued by the company for it. After reaching a settlement with Heublein, he sold the Colonel’s Lady restaurant, and it has continued to operate since then (currently as the “Claudia Sanders Dinner House”). It serves his “original recipe” fried chicken as part of its (non-fast-food) dinner menu, and it is the only non-KFC restaurant that serves an authorized version of the fried chicken recipe.

Sanders later used his stock holdings to create the Colonel Harland Sanders Trust and Colonel Harland Sanders Charitable Organization, which used the proceeds to aid charities and fund scholarships. His trusts continue to donate money to groups like the Trillium Health Care Centre; a wing of their building specializes in women’s and children’s care and has been named after him. The Sidney, British Columbia based foundation granted over $1,000,000 in 2007, according to its 2007 tax return. Sanders was diagnosed with acute leukemia in June 1980. He died at Jewish Hospital in Louisville, Kentucky of pneumonia on December 16, 1980 at the age of 90. His body lay in state in the rotunda of the Kentucky State Capitol in Frankfort after a funeral service at the Southern Baptist Seminary Chapel, which was attended by more than 1,000 people. He was buried in his characteristic white suit and black western string tie in Cave Hill Cemetery in Louisville. By the time of his death, there were an estimated 6,000 KFC outlets in 48 different countries worldwide, with $2 billion of sales annually.

Born

- September, 09, 1890

- USA

- Henryville, Indiana

Died

- December, 16, 1980

- USA

- Louisville, Kentucky

Cause of Death

- pneumonia

Cemetery

- Cave Hill Cemetery

- Louisville, Kentucky

- USA