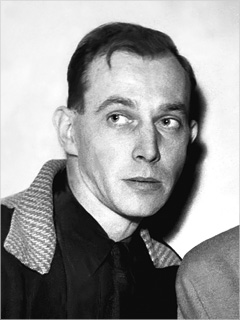

Chris Marker (Chris Marker)

Marker was born Christian François Bouche-Villeneuve. Always elusive about his past and known to refuse interviews and not allow photographs to be taken of him, his place of birth is highly disputed. Some sources and Marker himself claim that he was born in Ulan Bator, Mongolia. Other sources say he was born in Belleville, Paris, and others, in Neuilly-sur-Seine. The 1949 edition of Le Cœur Net specifies his birthday as 22 July. Film critic David Thomson has stated: “Marker told me himself that Mongolia is correct. I have since concluded that Belleville is correct – but that does not spoil the spiritual truth of Ulan Bator.” When asked about his secretive nature, Marker has said “My films are enough for them [the audience].”

Marker was a philosophy student in France prior to World War II. During the German occupation of France he joined the Maquis (FTP), a part of the French Resistance. At some point during the war he left France and joined the United States Air Force as a paratrooper, although some sources claim that this is a myth. After the war he began a career as a journalist. He first wrote for the journal Esprit, a neo-Catholic, Marxist magazine where he met fellow journalist André Bazin. At Esprit, Marker wrote political commentaries, poems, short stories and (with Bazin) film reviews. He would later become an early contributor to Bazin’s Cahiers du cinéma.

During this time period, Marker began to travel around the world as a journalist and photographer, a vocation he would continue the rest of his life. He was hired by the French publishing company Éditions du Seuil as editor of the series Petite Planète (Small World). This collection devoted one edition to each country and included information and photographs. In 1949 Marker published his first novel, Le Coeur net (The Forthright Spirit), which was about aviation. In 1952 Marker published an illustration essay on French writer Jean Giraudoux, Giraudoux Par Lui-Même.

During his early journalism career, Marker became increasingly interested in filmmaking and experimented with photography in the early 1950s. Around this time Marker met and befriended many members of what would be called the Left Bank Film Movement, including Alain Resnais, Agnès Varda, Henri Colpi, Armand Gatti and the novelists Marguerite Duras and Jean Cayrol. This group is often associated with the French New Wave directors who came to prominence during the same time period, and indeed both groups were often friends and journalistic co-workers. The term Left Bank was first coined by film critic Richard Roud, who has described them as having “fondness for a kind of Bohemian life and an impatience with the conformity of the Right Bank, a high degree of involvement in literature and the plastic arts, and a consequent interest in experimental filmmaking”, as well as an identification with the political left. Many of Marker’s earliest films were produced by Anatole Dauman.

In 1952 Marker made his first film, Olympia 52, a 16mm feature documentary about the 1952 Helsinki Olympic Games. In 1953 Marker collaborated with Resnais on the documentary Statues Also Die. The film examines traditional African art such as sculptures and masks, and its decline with coming of Western colonialism. The film won the 1954 Prix Jean Vigo, but was banned by French censors for its criticism of French colonialism.

After working as assistant director on Resnais’s Night and Fog in 1955, Marker made Sunday in Peking, a short documentary “film essay” that would characterize Marker’s unique film style for most of his career. The film was shot in two weeks by Marker while he was traveling through China with Armand Gatti in September 1955. In the film, Marker’s commentary overlaps scenes from China, such as tombs which, contrary to Westernized understandings of Chinese legends, do not contain the remains of any Ming Dynasty emperors.

After working on the commentary for Resnais’ film Le mystère de l’atelier quinze in 1957, Marker continued to form his own cinematic style with the feature documentary Letter from Siberia. An essay film on the narrativization of Siberia, it contains Marker’s signature commentary, which takes the form of a letter from the director, in the long tradition of epistolary treatments by French explorers of the “undeveloped” world. Letter looks at the modernization of Siberia with its movement into the twentieth century, but with a look back at some of the tribal cultural practices now receding into the past. It combines footage that Marker shot in Siberia with old newsreel footage, cartoon sequences, stills, and even an illustration of Alfred E. Neuman from Mad Magazine as well as a fake TV commercial as part of a humorous attack on Western mass culture. In producing a meta-commentary on narrativity and film, Marker uses the same brief filmic sequence three times but with different commentary—the first one praising the Soviet Union, the second denouncing it, and the third taking an apparently neutral or “objective” stance.

In 1959 Marker made the animated film Les Astronautes with Walerian Borowczyk. The film was a combination of traditional drawings with still photography. In 1960 Marker made Description d’un combat, a documentary on the State of Israel which reflects on the country’s past and future. The film won the Golden Bear for Best Documentary at the 1961 Berlin Film Festival. In January 1961, Marker traveled to Cuba and shot the film ¡Cuba Sí! The film promotes and defends Fidel Castro and includes two interviews with the Comandante. The film ends with an anti-American epilogue in which the United States is embarrassed by the Bay of Pigs Invasion fiasco, and was subsequently banned. The banned essay was included in Marker’s first volume of collected film commentaries, Commentaires I, published in 1961. The following year Marker published Coréennes, a collection of photographs and essays on the conditions of Korea.

Marker became known internationally for the short film La jetée (The Pier) in 1962. It tells of a post-nuclear war experiment in time travel by using a series of filmed photographs developed as a photomontage of varying pace, with limited narration and sound effects. In the film, a survivor of a futuristic third World War is obsessed with a distant and disconnected memories of a pier at the Orly Airport, the image of a mysterious woman, and a man’s death. Scientists experimenting in time travel choose him for their studies, and the man travels back in time to contact the mysterious woman, and discovers that the man’s death at the Orly Airport was his own. Except for one shot of the woman mentioned above sleeping and suddenly waking up, the film is composed entirely of photographs by Jean Chiabaud and stars Davos Hanich as the man, Hélène Chatelain as the woman and filmmaker William Klein as a man from the future.

La Jetée was the inspiration for Mamoru Oshii’s 1987 debut live action feature The Red Spectacles (and later for parts of Oshii’s 2001 film Avalon as well) and also inspired Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys (1995). It also inspired many of director Mira Nair’s shots for the 2006 film The Namesake.

While making La Jetee, Marker was simultaneously making the 150-minute documentary essay-film Le joli mai, released in 1963. Beginning in the Spring of 1962, Marker and his camera operator Pierre Lhomme shot 55 hours of footage interviewing random people on the streets of Paris. The questions, asked by the unseen Marker, range from their personal lives, as well as social and political issues of relevance at that time. Like he had with montages of landscapes and indigenous art, Marker created a film essay that contrasts and juxtaposes a variety of lives with his signature commentary (spoken by Marker’s friends, singer-actor Yves Montand in the French version and Simone Signoret in the English version). The film has been compared to the Cinéma vérité films of Jean Rouch, and criticized by its practitioners at the time. The term “Cinéma vérité” was itself anathema to Marker; he would never use it. It was shown in competition at the 1963 Venice Film Festival, where it won the award for Best First Work. It also won the Golden Dove Award at the Leipzig DOK Festival.

After the documentary Le Mystère Koumiko in 1965, Marker made Si j’avais quatre dromadaires, an essay-film that, like La jetée, is a photomontage of over 800 photographs that Marker had taken over the past 10 years from 26 countries. The commentary takes on a slightly different dimension than his previous commentaries by using a fictitious photographer have a conversation with two friends to discuss the photos. The film’s title is an allusion to a poem by Guillaume Apollinaire. It was the last film in which Marker includes “travel footage” for many years.

In 1967 Marker published his second volume of collected film essays, Commentaires II. That same year, Marker organized the omnibus film Loin du Vietnam, a protest against the Vietnam War with segments contributed by Marker, Jean-Luc Godard, Alain Resnais, Agnès Varda, Claude Lelouch, William Klein, Michele Ray and Joris Ivens. The film includes footage of the war, from both sides, as well as anti-war protests in New York and Paris and other anti-war activities.

From this initial collection of filmmakers with left-wing political agendas, Marker created the group S.L.O.N. (Société pour le lancement des oeuvres nouvelles, but also the Russian word for elephant). SLON was a film collective whose objectives were to make films and to encourage industrial workers to create film collectives of their own. Its members included Valerie Mayoux, Jean-Claude Lerner, Alain Adair and John Tooker. Marker is usually credited as director or co-director of all of the films made by SLON.

After the events of May 1968, Marker felt a moral obligation to abandon his own personal film career and devote himself to SLON and its activities. SLON’s first film was about a strike at a Rhodiacéta factory in France, À bientôt, j’espère (Rhodiacéta) in 1968. Later that year SLON made La Sixième face du pentagone, about an anti-war protest in Washington, D.C. and was a reaction to what SLON considered to be the unfair and censored reportage of such events on mainstream television. The film was shot by François Reichenbach, who received co-director credit. La Bataille des dix millions was made in 1970 with Mayoux as co-director and Santiago Álvarez as cameraman and is about the 1970 sugar crop in Cuba and its disastrous effects on the country. In 1971, SLON made Le Train en marche, a new prologue to Soviet filmmaker Aleksandr Medvedkin’s 1935 film Schastye, which had recently been re-released in France. In 1974, SLON became I.S.K.R.A. (Images, Sons, Kinescope, Réalisations, Audiovisuelles, but also the name of Vladimir Lenin’s political newspaper Iskra).

Beginning with Sans Soleil, he developed a deep interest in digital technology, which led to his film Level Five (1996) and Immemory (1998, 2008), an interactive multimedia CD-ROM, produced for the Centre Pompidou (French language version) and from Exact Change (English version). Marker created a 19-minute multimedia piece in 2005 for the Museum of Modern Art in New York City titled Owls at Noon Prelude: The Hollow Men which was influenced by T. S. Eliot’s poem.

Marker lived in Paris and very rarely granted interviews. One exception was a lengthy interview with Libération in 2003 in which he explained his approach to filmmaking. When asked for a picture of himself, he usually offered a photograph of a cat instead. (Marker was represented in Agnes Varda’s 2008 documentary “The Beaches of Agnes” by a cartoon drawing of a cat, speaking in a technologically altered voice.) Marker’s own cat is named Guillaume-en-egypte. In 2009 Marker commissioned an Avatar of Guillaume-en-Egypte to represent him in machinima works. The avatar was created by Exosius Woolley and first appeared in the short film / machinima, “Ouvroir the Movie by Chris Marker.”

In the 2007 Criterion Collection release of La Jetée and Sans Soleil, Marker included a short essay, “Working on a shoestring budget”. He confessed to shooting all of Sans Soleil with a silent film camera and recording all the audio on a primitive audio cassette recorder. Marker also reminds the reader that only one short scene in La Jetée is of a moving image, as Marker could only borrow a movie camera for one afternoon while working on the film. Marker died on 29 July 2012, 91 years, to the day he was born.

Born

- July, 29, 1921

- Neuilly-sur-Seine, Île-de-France

Died

- July, 29, 2012

- Paris, France