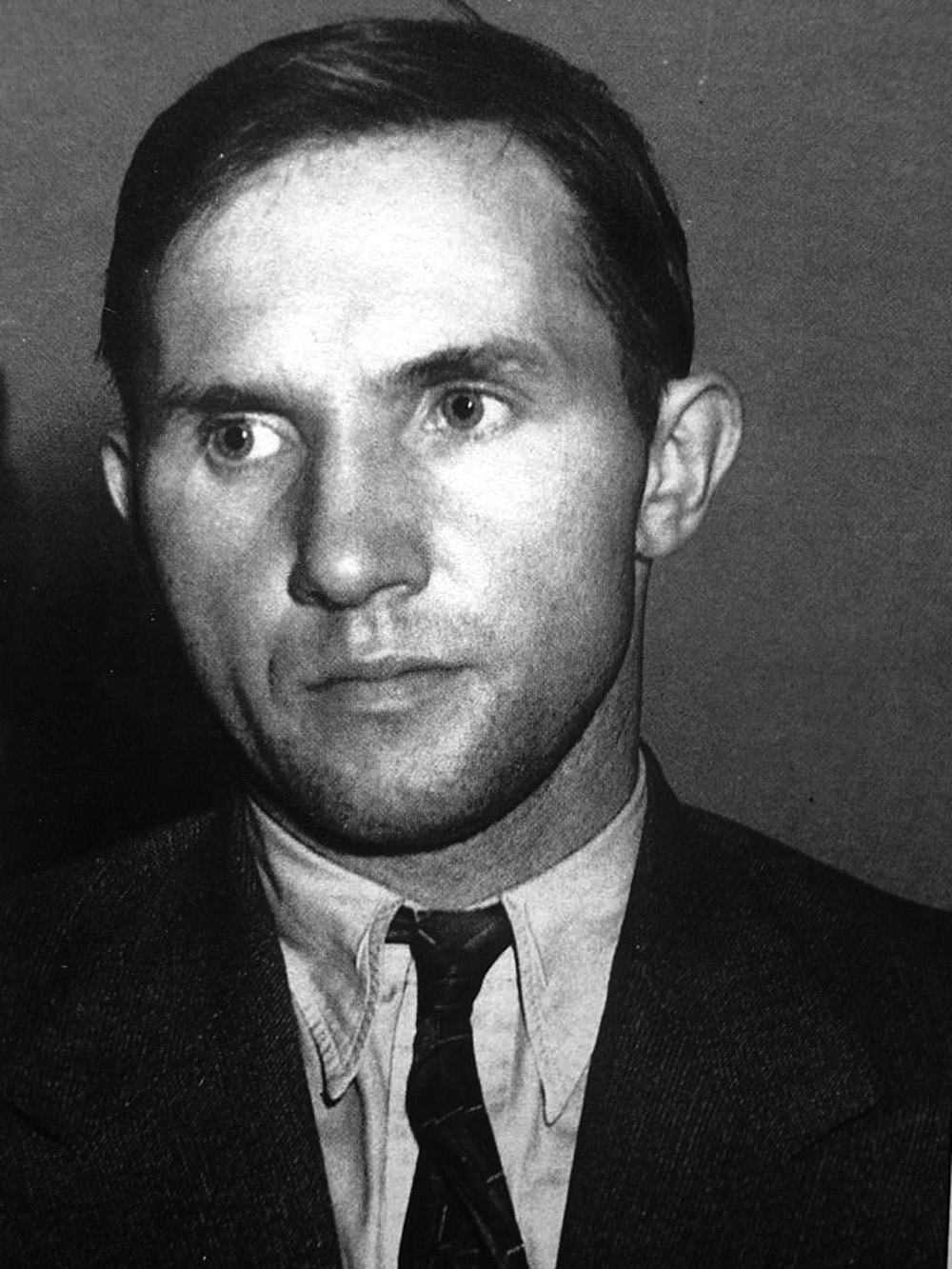

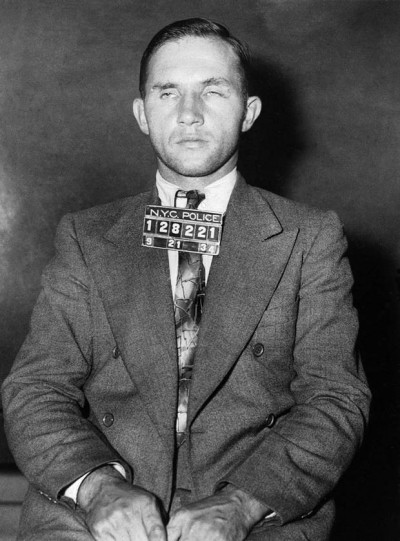

Bruno Hauptmann (Bruno Richard Hauptmann)

Hauptmann was born Richard Hauptmann in Kamenz, near Dresden in what was then the German Empire, the youngest of five children. (The name “Bruno,” used sometimes by prosecutors in the Lindbergh kidnapping trial was not used by family or friends.) He had three brothers and a sister. At age 11, he joined the Boy Scouts (Pfadfinderbund). Hauptmann attended public school (Realschule), but quit at the age of 14. He then worked during the day while attending trade school (Gewerbeschule) at night, studying carpentry for the first year, then switching to machine building (Maschinenschlosser) for the next two years. In 1917, Hauptmann’s father died. The same year, Hauptmann learned his brother Herman had been killed fighting in France in World War I. Not long after that, he was informed that his brother Max was now dead too, having fallen in Russia. Shortly thereafter, Hauptmann was conscripted and assigned to the artillery.

Upon receiving his orders, he was sent to Bautzen, but was transferred to the 103rd Infantry Replacement Regiment upon his arrival. In 1918, Hauptmann was assigned to the 12th Machine Gun Company at Königsbrück. Hauptmann would claim that he was deployed to Western France with the 177th Regiment of Machine Gunners in either August or September 1918 then fought in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel. Hauptmann would also say he was gassed in either September or October 1918. He also claimed that while his position was being shelled, he was hit in the helmet with a piece of metal. According to him, this knocked him out for hours, and he was left for dead. When he came to, he crawled back to safety and was back to the machine guns that evening. After the war, Hauptmann and a friend robbed two women wheeling baby carriages they were using to transport food on the road between Wiesa and Nebelschütz. The friend wielded Hauptmann’s army pistol during the commission of this crime. Hauptmann’s other charges include burglarizing a mayor’s house (using a ladder). Released after three years in prison, he was arrested three months later on suspicion of further burglaries.

Hauptmann illegally entered the US by stowing away on a liner. Landing in New York in September 1923, the 24-year-old Hauptmann was taken in by a member of the established German community and worked as a carpenter. He married a German waitress in 1925 and became a father eight years later. Hauptmann was slim and of medium height, but broad shouldered. His eyes were described as being small and deep-set.

The kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr. occurred on the evening of March 1, 1932. A man was believed to have climbed up a ladder placed under the bedroom window of the child’s room and quietly snatched the infant by wrapping him in a blanket. A note demanding a ransom of $50,000 was left on the radiator that formed a windowsill for the room. The ransom was delivered, but the infant was not returned. A corpse identified as the boy’s was found on May 12, 1932, in the woods 4 miles (6.4 km) from the Lindbergh home. The cause of death was listed as a blow to the head. It has never been determined whether the head injury was accidental or deliberate; some have theorized that the fatal injury occurred accidentally during the abduction. During the opening to the jury in the trial, New Jersey Attorney General David Wilentz claimed the child died by a fall from the ladder. However during the state’s summation, Wilentz would claim the child was killed in the nursery after having been hit in the head with the chisel found at the scene. This material variance in theory as to both the location and cause of death by the state was one of the major points included in Hauptmann’s appeal process. More than two years after the abduction, authorities finally discovered a promising lead in the form of recent ransom notes which appeared to be the work of the very same individual. Soon this information was leaked to the press, which sought verification that the police were closing in on the kidnapper or kidnappers.

Then, on September 17, 1934, a $10 gold certificate that was part of the ransom was given to a gas station attendant as payment. Gold certificates were rapidly being withdrawn from circulation; to see one was unusual and, in this case, attracted attention. The attendant wrote down the license plate number of the car and gave it to the police. The New York license plate belonged to a dark blue Dodge sedan owned by Hauptmann. After successfully tracing the plate to Hauptmann, he was placed under surveillance by a team consisting of members of the New York Police Department, New Jersey State Police, and the FBI. On the morning of September 19, 1934, the team followed Hauptmann as he left his apartment on Needham Avenue and East 222nd Street in the Bronx, but were quickly noticed. As a result, Hauptmann attempted to get away by ignoring red lights and traveling at high speed. As the chase continued, Hauptmann was accidentally boxed in by a municipal sprinkler truck between 178th Street and East Tremont Avenue. Hauptmann was placed in handcuffs.

The trial attracted widespread media attention and was dubbed the “Trial of the Century”. Hauptmann was also named “The Most Hated Man in the World”. The trial was held in Flemington, New Jersey, and ran from January 2 to February 13, 1935. Col. Henry S. Breckinridge was Lindbergh’s lawyer throughout the case and had acted as an intermediary in the ransom negotiations, assisted by Robert H. Thayer. On discovering his child was missing, Lindbergh had phoned Breckinridge before calling the state police.

Evidence produced against Hauptmann included $14,590 of the ransom money found in his garage and testimony alleging handwriting and spelling similarities to that found on the ransom notes. Eight different handwriting experts (Albert S. Osborn, Elbridge W. Stein, John F. Tyrrell, Herbert J. Walter, Harry M. Cassidy, Wilmer T. Souder, Albert D. Osborn, and Clark Sellers)[18] were called by the prosecution to the witness stand, where they pointed out similarities between words and letters in the ransom notes and in Hauptmann’s writing specimens (which included documents written before he was arrested, such as automobile registration applications). One expert (John M. Trendley) was called by the defense to rebut this evidence, while two others (Samuel C. Malone and Arthur P. Meyers) declined to testify;[18] the latter two demanded $500 for their services before even looking at the notes and were promptly dismissed when defense lawyer Fisher declined.[19] Others who claimed expertise (Goodspeed, Braunlich, Foster, Farr, and Thielen) were also retained by the defense. They were told they would testify but, much to their dismay, were never called to the stand by lead attorney Reilly.

Also presented was the handmade ladder used in the kidnapping, along with forensic testimony by Arthur Koehler, chief wood technologist at the Forest Products Laboratory. Koehler had, earlier in the investigation and prior to Hauptmann’s arrest, written a report that the ladder’s “Rail 16” had probably originated from the interior of a building, possibly an attic, due to the fact there was no rust in the nail holes or discoloration around the heads. Koehler asserted this was evidence it had not been exposed to the weather. Koehler would testify at the trial that Rail 16 matched a part of a board (S-226) from Hauptmann’s attic floor which had a missing piece.

Other evidence included Dr. Condon’s address and telephone number, which were found written on the inside of one of Hauptmann’s closets (Condon had delivered the ransom). Additionally, a hand-drawn sketch which Wilentz suggested was that of a ladder was found in one of Hauptmann’s notebooks (S-261). Hauptmann said this picture, along with various other sketches contained therein, had been the work of a child who had drawn in it. Despite not having an obvious source of employment, he had enough money to purchase a large $400 radio (nearly $7,000 today) and to send his wife on a trip to Germany (the purpose of the trip being to see whether Hauptmann would be arrested for having committed earlier crimes there). Hauptmann was positively identified as the man to whom the ransom money was delivered. Other witnesses testified that it was Hauptmann who had spent some of the Lindbergh gold certificates, that he had been seen in the area of the estate in East Amwell, New Jersey near Hopewell on the day of the kidnapping, and that he had been absent from work on the day of the ransom payment and quit his job two days later.

When the prosecution rested, the defense opened up their case with a lenghly examination by Hauptmann himself. In his testimony, Hauptmann denied being guilty, insisting that the box that was found to contain the gold certificates had been left in his garage by a friend named Isidor Fisch, who had returned to Germany in December 1933 and died there in March 1934. Hauptmann claimed that he had found a shoe box left behind by Fisch, which Hauptmann had stored on the top shelf of a kitchen broom closet, later discovering the money which, upon counting, added up to nearly $40,000. He further claimed that since Fisch owed him around $7,500 in business funds, Hauptmann claimed the money for himself. A ledger was found in Hauptmann’s home of all his financial transactions; yet, no record of the alleged $7,500 debt was listed.

Hauptmann’s defense lawyer, Edward J. Reilly, next called Hauptmann’s wife Anna to the witness stand to corroborate the Fisch story. But upon cross-examination by chief prosecutor David T. Wilentz, she was forced to admit that while she hung her apron every day on a hook higher than the top shelf, she could not remember seeing any shoe box there. Later, rebuttal witnesses testified that Fisch could not have been at the scene of the crime, and that he had no money for medical treatments when he died in Germany of tuberculosis. Fisch’s landlady testified that he could barely afford his $3.50-a-week room. Various witnesses called by Reilly to put Fisch near the Lindbergh house on the night of the kidnapping were discredited in cross-examination with incidents from their pasts, which included criminal records or mental instability.[citation needed] In his closing summation, Reilly argued that the evidence against Hauptmann was entirely circumstantial, as no reliable witness had placed Hauptmann at the scene of the crime, nor were his fingerprints found on the ladder, the ransom notes, or anywhere in the nursery. Hauptmann was convicted and immediately sentenced to death by Judge Trenchard who set the date for the week of March 18, 1935.

The Hauptmann Defense appealed to the New Jersey Court of Errors and Appeals which, as a result, delayed the execution. The appeal was then argued on June 29, 1935. New Jersey Governor Harold G. Hoffman secretly visited Hauptmann in his death row cell on the evening of October 16, 1935, with Anna Bading, a stenographer and fluent speaker of German. Hoffman urged members of the New Jersey Court of Errors and Appeals, then the state’s highest court, to visit Hauptmann. In late January 1936, while clearly stating he held no position on the guilt or innocence of Hauptmann, Governor Hoffman cited evidence the crime was not a “one person” job. He then directed Col. Schwarzkopf to continue a thorough and impartial investigation into the kidnapping in an effort to bring all parties involved to justice.

As time was quickly running out for Hauptmann, it became known among the press that on March 27, Governor Hoffman was considering a second reprieve of his death sentence, but was actively seeking advice concerning the legality of his right as governor to do so. On March 30, 1936, Hauptmann’s second and final application asking for clemency from the New Jersey Board of Pardons was denied. The Governor would later announce this decision would be the final legal action in this Case, and that he would not grant another reprieve. However, a postponement in the execution would occur once again when the Mercer County Grand Jury, investigating the confession and arrest of Paul Wendel, requested Warden Mark Kimberling for a delay. This final stay would come to an end when the Mercer County Prosecutor informed Kimberling the Grand Jury had adjourned after voting to discontinue its investigation concerning Wendel without any complaint charging him with murder.

On April 3, 1936, Hauptmann was executed in “Old Smokey”, the electric chair at the New Jersey State Prison. Hauptmann’s last meal consisted of coffee, milk, celery, olives, salmon salad, corn fritters, sliced cheese, fruit salad, and cake. Reporters present at the execution reported that he went to the electric chair without saying a word. He had addressed his last words to his spiritual advisor, Rev. James Matthiesen, minutes prior to being taken from his cell to the death chamber. He reportedly said, “Ich bin absolut unschuldig an den Verbrechen, die man mir zur Last legt”, which Matthiesen told Gov. Hoffman meant “I am absolutely innocent of the crime with which I am burdened.” After the execution, Hauptmann’s widow applied for and received the special permission that was required to take her husband’s body out of state so that it could be cremated at the U.S. crematory (also called the Fresh Pond Crematory) in the Maspeth neighborhood of Queens, New York. The memorial service there was religious (two Lutheran pastors conducted the service in German) and private (under New Jersey law, public services were not permitted for felons, and Anna Hauptmann had agreed to this as a condition of receiving her husband’s body) and was attended by only six people (the legal limit under New Jersey rules), but a crowd of over 2,000 gathered outside. Hauptmann’s widow had planned to return to Germany with the ashes. Anna Hauptmann died in 1994 at age 95.

Born

- November, 26, 1899

- Germany

- Kamenz, Saxony

Died

- April, 03, 1936

- USA

- Trenton, New Jersey

Cause of Death

- execution by electric chair

Other

- Cremated