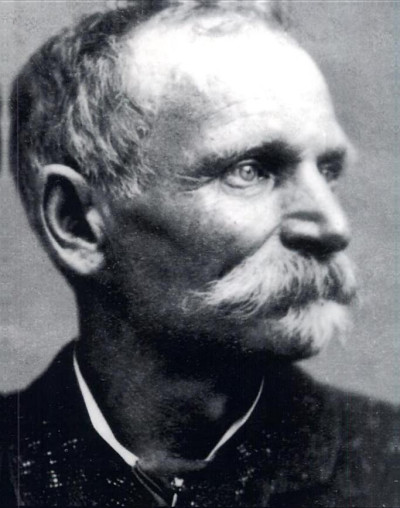

Black Bart (Charles Earl Bowles)

Charles Bowles was born in Norfolk, England to John and Maria Bowles (sometimes spelled Bolles). He was the third of ten children, having six brothers and three sisters. When Charles was two years old, his parents emigrated to Jefferson County, New York, where his father purchased a farm, four miles north of Plessis Village in the direction of Alexandria Bay. In late 1849, Bowles and two of his brothers, David and James, took part in the California Gold Rush and began mining in the North Fork of the American River in California. Bowles mined for only a year before returning home in 1852, but soon returned to California, accompanied once again by his brother David and joined by another brother, Robert. Both brothers became ill and died in California soon after their arrival. Bowles continued mining for two more years before leaving.

In 1854, Bowles (who had by now adopted this spelling of his surname) married Mary Elizabeth Johnson, with whom he had four children. By 1860, the couple had made their home in Decatur, Illinois. The American Civil War began in April 1861, and on August 13, 1862, Bowles enlisted in Decatur, Illinois, as a private in Company B, 116th Illinois Regiment, (his last name is spelled as “Boles” in his service records). He proved to be a good soldier, rising to the rank of first sergeant within a year and took part in numerous battles, including the Battle of Vicksburg, where he was seriously wounded, and Sherman’s March to the Sea. He received brevet commissions as both second lieutenant and first lieutenant, and on June 7, 1865, was discharged in Washington, D.C. and returned home to Illinois. In 1867, he began prospecting again, this time in Idaho and Montana. Little is known of his life during this time, but in a letter to his wife in August 1871, he mentioned an unpleasant incident involving some Wells, Fargo & Company employees and vowed to exact revenge. He then stopped writing, and after a while his wife assumed he was dead.

Bowles, as Black Bart, perpetrated 28 robberies of Wells Fargo stagecoaches across northern California between 1875 and 1883, including a number of robberies along the historic Siskiyou Trail between California and Oregon. Although he only left two poems – at the fourth and fifth robbery sites – this came to be considered his signature and ensured his fame. Black Bart was very successful, absconding with thousands of dollars a year. Bowles was terrified of horses and committed all of his robberies on foot. This, together with his poems, earned him notoriety. Additionally, throughout his years as a highwayman, he never fired a gun. Bowles was always courteous and used no foul language in speech, although this aversion to profanity is not evident in his poems. He wore a long linen duster coat and a bowler hat, covered his head using a flour sack with holes cut for the eyes, and brandished a shotgun. These distinguishing features became his trademarks.

On July 26, 1875, Bowles robbed his first stagecoach in Calaveras County, on the road between Copperopolis and Milton. What made the crime unusual were the politeness and good manners of the outlaw. He spoke with a deep and resonant tone and told John Shine, the stagecoach driver, “Please throw down the box.” As Shine handed over the strongbox, Bowles shouted, “If he dares to shoot, give him a solid volley, boys”. Seeing rifle barrels pointed at him from the nearby bushes, Shine handed over the strongbox. Shine waited until Bowles vanished and then went back to get the plundered box. Upon returning to the scene, he found that the “men” with rifles in the bushes were actually carefully rigged sticks. This first robbery netted Bowles $160.

The last holdup took place on November 3, 1883 at the same site as his first holdup, on Funk Hill just southeast of the present town of Copperopolis. The stage, driven by Reason McConnell, had crossed the Reynolds Ferry on the old stage road from Sonora to Milton. At the ferry crossing, the driver picked up Jimmy Rolleri, the 19-year-old son of the ferry owner. Jimmy Rolleri had brought his rifle and got off at the bottom of Funk Hill, intending to hunt along the creek at the southern base of the hill and then meet the stage on the other side as it came down the western grade. However, on arriving at the western side of the hill, he found that the stage was not there. He began walking up the stage road, and on nearing the summit, he encountered the stage driver and his team of horses.

Rolleri learned that as the stage had approached the summit, Bowles had stepped out from behind a rock with his shotgun. He made McConnell unhitch the team and take them over the crest to the west side of the hill, where he met Rolleri coming up. Bowles then tried to remove the strongbox from the stage, but the strongbox had been bolted to the floor inside the stage (which had no passengers that day), and it took Bowles some time to remove it. McConnell informed Rolleri that a holdup was in progress, and Rolleri approached McConnell and the horses to see Bowles backing out of the stage with the box. McConnell took Rolleri’s rifle and fired at Bowles twice as he started to run away; both shots missed. Rolleri then took the rifle and fired just as Bowles was entering a thicket. They saw him stumble as he had been hit. Running to where they had last seen the robber, they found a bundle of mail he had dropped, some of which had blood on it.

Bowles had been hit in the hand. After running about a quarter of a mile he stopped, too tired to run any farther, and he wrapped a handkerchief around the wound to help stop the bleeding. He found a rotten log and stuffed the sack with the gold amalgam into it, keeping $500 in gold coins. Bowles buried the shotgun in a hollow tree, threw everything else away, and escaped. It should be noted that there is a manuscript written by stage driver Reason McConnell some 20 years after the robbery, in which McConnell says that he fired all four shots at Bowles. The first was a misfire, but he thought the second or third shot hit Bowles, and he knew that the fourth one hit him. Bowles only had the wound to his hand, and if the other shots hit his clothing, Bowles was unaware of it.

During his last robbery in 1883, when Bowles was wounded and forced to flee the scene, he left behind several personal items, including a pair of eyeglasses, food, and a handkerchief with a laundry mark F.X.O.7. Wells Fargo Detective James B. Hume (who allegedly looked enough like Bowles to be a twin brother, mustache included) found these personal items at the scene. He and detective Harry N. Morse contacted every laundry in San Francisco seeking the one that used the mark on the handkerchief. After visiting nearly 90 laundry operators, they finally traced the mark to Ferguson & Bigg’s California Laundry on Bush Street and were able to identify the handkerchief as belonging to Bowles, who lived in a modest boarding house.

Bowles described himself as a “mining engineer” and made frequent “business trips” that happened to coincide with the Wells Fargo robberies. After initially denying he was Black Bart, Bowles eventually admitted that he had robbed several Wells Fargo stages but confessed only to the crimes committed before 1879. It is widely thought that Bowles mistakenly believed that the statute of limitations had expired on those robberies. When booked, he gave his name as T.Z. Spalding. When the police examined his possessions they found a Bible, a gift from his wife, inscribed with his real name. The police report following his arrest stated that Bowles was “a person of great endurance. Exhibited genuine wit under most trying circumstances, and was extremely proper and polite in behavior. Eschews profanity.”

Wells Fargo pressed charges only on the final robbery. Bowles was convicted and sentenced to six years in San Quentin Prison, but his stay was shortened to four years for good behavior. When he was released in January 1888, his health had clearly deteriorated due to his time in prison. He had visibly aged, his eyesight was failing, and he had gone deaf in one ear. Reporters swarmed around him when he was released and asked if he was going to rob any more stagecoaches. “No, gentlemen,” he replied, smiling. “I’m through with crime.” Another reporter asked if he would write more poetry. Bowles laughed and said, “Now, didn’t you hear me say that I am through with crime?”

Bowles never returned to his wife after his release from prison, though he did write to her. In one of the letters he said he was tired of being shadowed by Wells Fargo, felt demoralized, and wanted to get away from everybody. In February 1888, Bowles left the Nevada House and vanished. Hume said Wells Fargo tracked him to the Palace Hotel in Visalia. The hotel owner said a man answering the description of Bowles had checked in and then disappeared. The last time the outlaw was seen was February 28, 1888.

Born

- April, 19, 2025

- Norfolk, England

Died

- February, 28, 1888