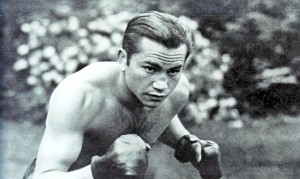

Barney Ross (Dov-Ber Rasofsky)

Barney Ross

Dov-Ber (or Beryl) Rosofsky was born in New York City to Isidore “Itchik” Rosofsky and Sarah Epstein Rosofsky. His father was a Talmudic scholar who had emigrated to America from his native Brest-Litovsk after barely surviving a pogrom. The family then moved from New York to Chicago. Isidore became a rabbi and owner of a small vegetable shop in Chicago’s Maxwell Street neighborhood, a vibrant Jewish ghetto akin to the New York’s Lower East Side of the 1920s and ’30s. Dov-Ber was being raised to follow in his footsteps.

The young Rasofsky grew up on Chicago’s mean streets, ultimately ignoring his father’s desire for him to become a rabbi and his admonition that Jews do not resort to violence. “‘Let the goyim be the fighters,'” Ross later recalled being told by his father. “‘The trumbeniks, the murderers – we are the scholars.'” Ross’s ambition in life was to become a Jewish teacher and a Talmudic scholar, but his life was changed forever when his father was shot dead resisting a robbery at his small grocery. Prostrate from grief, his mother Sarah suffered a nervous breakdown and his younger siblings—Ida, Sam and George-were placed in an orphanage or farmed out to other members of the extended family. Dov was left to his own devices at the age of 14.

As recounted in Barney Ross: The Life of A Jewish Fighter, by Ross biographer Douglas Century, in the wake of the tragedy, Dov became vindictive towards everything and turned his back on the orthodox religion of his father. He began running around with local toughs (including another wayward Jewish ghetto kid, the future Jack Ruby), developing into a street brawler, thief and money runner; he was even employed by Al Capone. Dov’s goal was to earn enough money to buy a home so that he could reunite his family. He saw boxing as that vehicle and began training with his friend Ruby.

After winning amateur bouts, Dov would pawn the awards—like watches—and set the money aside for his family. There is speculation that Capone bought up tickets to his early fights, knowing some of that money would be funneled to Dov. Plagued by his father’s death and feeling an obligation not to sully his name, Dov Rosofsky took the new name “Barney Ross.” The name change was also part of a larger trend by Jews to assimilate in the U.S. by taking American-sounding names. Strong, fast and possessed of a powerful will, Ross was soon an Intercity Golden Gloves and Chicago Golden Gloves champion champion in 1929 at the age of 19 and went on to dominate the lighter divisions as a pro.

At a time—the late 1920s and ’30s—when rising Nazi leader Adolf Hitler was using propaganda to spread his virulently anti-Jewish philosophy, Ross was seen by American Jews as one of their greatest advocates. He represented the concept of Jews finally fighting back. Idolized and respected by all Americans, Ross showed that Jews could thrive in their new country. He made his stand against Hitler and Nazi Germany a public one. He knew that by winning boxing matches, he was displaying a new kind of strength for Jews. He also understood that Americans loved their sports heroes and if Jews wanted to be embraced in the U.S. they would have to assume such places in society. So even though Ross had lost faith in religion, he openly embraced his role as a leader of his oppressed people.

Ross occupies the rarefied place as one of boxing’s few triple division champions—lightweight, light welterweight and welterweight. He was never knocked out in 81 fights and held his title against some of the best competition in the history of the divisions. Ross defeated great Hall-of-Fame champions like Jimmy McLarnin and Tony Canzoneri in epic battles that drew crowds of more than 50,000.

His first paid fight was on September 1, 1929, when he beat Ramon Lugo by a decision in six rounds. After ten wins in a row, he lost for the first time, to Carlos García, on a decision in ten.

Over the next 35 bouts, his record was 32–1–2, including a win over former world champion Battling Battalino and one over Babe Ruth (not the baseball player). Another bout included former world champion Cameron Welter. Then, on March 26, 1933, Ross was given his first shot at a world title, when he faced world lightweight and light welterweight champion and fellow three-division world champion Tony Canzoneri in Chicago. In one night, Ross became a two-division world champion when he beat Canzoneri by a decision in ten rounds. It should be pointed out that Ross campaigned heavily in the city of Chicago. After two more wins, including a knockout in six over Johnny Farr, Ross and Canzoneri boxed again, with Ross winning again by decision, but this time in 15.

Ross was known as a smart fighter with great stamina. He retained his title by decision against Sammy Fuller to finish 1933 and against Peter Nebo to begin 1934. Then he defended against former world champion Frankie Klick, against whom he drew in ten. Then came the first of three bouts versus Jimmy McLarnin. Ross vacated the light welterweight title to go after McLarnin’s welterweight title and won by a 15 round decision, his third world championship. However, in a rematch a few weeks later, McLarnin beat Ross by a decision and recovered the title. After that, Ross went back down to light welterweight and reclaimed his title with a 12-round decision over Bobby Pacho. After beating Klick and Henry Woods by decision to retain that title, he went back up in weight for his third and last fight with McLarnin; he recovered the welterweight title by outpointing McLarnin again over 15 rounds. He won 16 bouts in a row after that, including three over future world middleweight champion Ceferino Garcia and one against Al Manfredo. His only two defenses, however, over that stretch were against Garcia and against Izzy Jannazzo, on points in 15 rounds.

In his last fight, Ross defended his title on May 31, 1938 against fellow three-division world champion Henry Armstrong, who beat him by a decision in 15. Although Armstrong pounded Ross inexorably and his trainers begged him to let them stop the fight, Ross refused to stop or go down. Barney Ross had never been knocked out in his career[2] and was determined to leave the ring on his feet. Some boxing experts view Ross’s performance against Armstrong as one of the most courageous in history. Some believe that Ross’s will to survive every tough fight on his feet had to do with his understanding of his symbolic importance to Jews. That is, Jews would not only fight back, but they would not go down.

Ross retired with a record of 72 wins, four losses, three draws and two no decisions (Newspaper Decisions: 2-0-0), with 22 wins by knockout. He was ranked #21 on Ring Magazine ’s list of the 80 Best Fighters of the Last 80 Years.

Born

- December, 23, 1909

- New York, New York City

Died

- January, 17, 1967

- Chicago, Illinois

Cause of Death

- throat cancer

Cemetery

- Zion Gardens Cemetery

- Chicago, Illinois