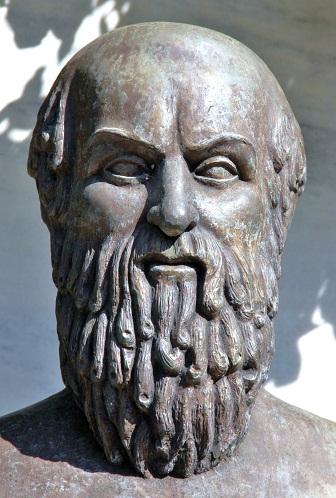

Aeschylus (Aeschylus Aeschylus)

Playwright, Director, Composer. One of the three giants of Ancient Greek drama, along with Sophocles and Euripides. He lived from 525 to 456 BC. Aeschylus has been called “The Father of Tragedy” for his fundamental innovations in writing and stagecraft. Of his estimated 90 plays, only seven have come down to us complete and his authorship of one, “Prometheus Bound”, is disputed. But those that survive bear witness to his importance, as do numerous testimonials throughout antiquity. The “Oresteia” (458 BC), a trilogy of dramas comprising “Agamemnon”, “The Libation Bearers”, and “The Eumenides”, is considered his masterpiece. The others are “The Persians” (472 BC), arguably the world’s oldest existing play; “Seven Against Thebes” (467 BC); and “The Suppliants” (c. 463 BC). Aeschylus was born into an aristocratic family in Eleusis, Attica, an area ruled by the city-state of Athens. From the beginning of the 5th Century BC, Athenian democracy and Athenian tragedy evolved side by side, and Aeschylus staunchly defended both as a playwright and soldier. He fought against the invading Persians at the Battle of Marathon (490 BC), in which his brother Cynegeirus died a hero’s death, and was recalled to military duty during the invasion of Xerxes (480 to 479 BC), seeing action at the Battles of Salamis and Plataea. These events influenced his writing, especially “The Persians”. We know little of his early theatre career except that it began around 500 BC. A regular competitor at the Festival of Dionysus (City Dionysia) in Athens, he failed to win a prize for tragedy until 484 BC, but afterwards he scored 12 more victories and dominated his rivals at least until the rise of Sophocles in the mid-460s. In 476 BC he accepted an invitation to visit the Sicilian court of Hiero I, the Tyrant of Syracuse; he returned to Sicily in 458 BC, this time going to Gela, where he died. A popular myth claims Aeschylus left Athens to escape a prophecy that he would die of “a blow from heaven”, only to be killed when an eagle mistook his bald head for a stone and dropped a tortoise on it. He was buried at Gela, not in the necropolis but among the public monuments in the city itself, a great honor. Tradition says he wrote his own epitaph, which commemorated his military exploits rather than his fame as a playwright. His sons Euphorion and Euaeon and his nephew Philocles became playwrights themselves. Euphorion famously defeated Sophocles and Euripides at the City Dionysia in 431 BC, and modern scholars have proposed him as the actual author of “Prometheus Bound”, noting its stylistic inconsistencies with his father’s other plays. The dramas of Aeschylus are bound by an unbending sense of moral and religious responsibility. He broadened the scope of tragedy by giving the actions of individuals equal dramatic footing with the power of gods; his plots encompassed struggles between human and deity, and issues of guilt and punishment over several generations. His language has a solemn grandeur perfectly suited to his weighty themes. Aeschylus directed many of his plays, and his pioneering developments were those of an imaginative yet practical man of the theatre. Early Greek tragedy consisted of a single performer exchanging dialogues with the chorus. Aeschylus brought in a second actor, making interaction and conflict between characters possible for the first time. He also introduced spectacular costumes and props, and may have been the first to employ the mechane, a crane that allowed actors to simulate flight high above the stage. Some of his effects were reportedly so terrifying that women in the audience suffered miscarriages and children fainted; the exaggerations suggest they must indeed have been impressive. The music Aeschylus composed for his plays seems to have emphasized their ceremonial aspects. In his choral odes he alternated sung, chanted, and spoken passages, and he experimented with silence as a dramatic effect. Aristophanes, in his comedy “The Frogs” (405 BC), has Aeschylus and Euripides mocking each other’s literary and musical styles in Hades, with Aeschylus getting in the best jokes. The “Oresteia”, Aeschylus’s last work, won first prize at the City Dionysia in 458 BC. At that time it was customary for a playwright to present three tragedies on related themes in a single day, followed by a bawdy satyr play to lighten the mood of the audience. (A comedy by another playwright would conclude the program). The “Oresteia” is the only extant example of such a trilogy, though the satyr play Aeschylus wrote for it, “Proteus”, is lost. It forms a continuous drama about the mythological Curse of the House of Atreus. In “Agamemnon”, the titular King of Argos returns home from the Trojan War and is murdered by his wife Clytemnestra, in collusion with a lover she had taken in his absence, the weakling Aegisthus. His death makes Clytemnestra the de facto ruler of Argos, though she vows it was to avenge her daughter Iphigenia, whom Agamemnon had killed in a human sacrifice at the start of the war. The chorus reminds the usurpers that Agamemnon’s son Orestes is still alive in exile, and will come seeking blood. This sets the stage for “The Libation Bearers”. Orestes arrives in Argos under a command from the god Apollo, who has threatened him with the Furies – female deities of vengeance – if he fails to exact retribution for his father. His plan is put into action with the aid of his sister Electra and the chorus, which warns him that Clytemnestra is already suspicious due to nightmares of impending doom. In a powerful scene Orestes quickly dispatches Aegisthus but hesitates before slaying his mother, torn between duties to father, mother, and the gods, and hopelessly aware of the fate that awaits him whether he acts or not. He completes the gruesome task. Matricide was also punishable by the Furies, and in “The Eumenides” they pursue Orestes and drive him to madness. In Athens he is granted a trial by the goddess Athena, with the Furies the accusers, Apollo his defense, and the Athenian people serving as jurors. The jury splits in their decision and Orestes is one vote away from a murder conviction, but Athena shows mercy and votes in his favor, resulting in a tie and, by Athenian law, his acquittal. She placates the Furies by upgrading their godly status and admonishes all that justice should be determined by the democratic legal process, not through blood feuds. With that the Curse of Atreus is finally broken. There have been many modern retellings of the “Oresteia”, among them Eugene O’Neill’s “Mourning Becomes Electra” (1931) and Jean-Paul Sartre’s “The Flies” (1943). (bio by: Bobb Edwards) Inscription:”Beneath this stone lies Aeschylus, son of Euphorion, the Athenian, who died in the wheat-bearing land of Gela; of his noble prowess the grove of Marathon can speak, and the long-haired Persian knows it well”.

Born

- January, 01, 1970

- unknown

Died

- January, 01, 1970

- unknown

Cemetery

- Sicily