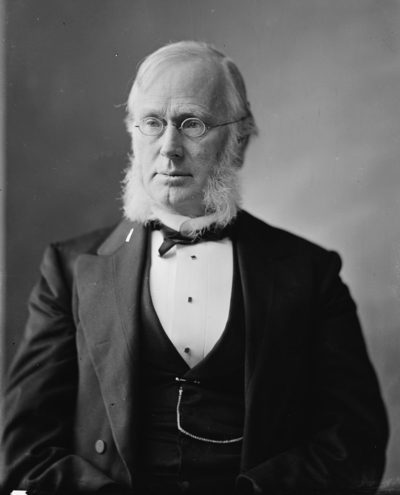

George Hoar (George Frisbie Hoar)

George Hoar graduated from Harvard University in 1846, then studied at Harvard Law School and settled in Worcester, Massachusetts where he practiced law before entering politics. Initially a member of the Free Soil Party, he joined the Republican Party shortly after its founding, and was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives (1852), and the Massachusetts Senate (1857). In 1865, Hoar was one of the founders of the Worcester County Free Institute of Industrial Science, now the Worcester Polytechnic Institute. He represented Massachusetts as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives from 1869 through 1877, then served in the U.S. Senate until his death. He was a Republican, who generally avoided party partisanship and did not hesitate to criticize other members of his party whose actions or policies he believed were in error. George Hoar was long noted as a fighter against political corruption, and campaigned for the rights of African Americans and Native Americans. He argued in the Senate in favor of Women’s suffrage as early as 1886. He opposed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, describing it as “nothing less than the legalization of racial discrimination.” However, he also believed that Portuguese and Italian immigrants were unfit for U.S. citizenship. As a member of the Congressional Electoral Commission, he was involved with settling the highly disputed U.S. presidential election, 1876. He authored the Presidential Succession Act of 1886, and in 1888 he was chairman of the 1888 Republican National Convention.

Unlike many of his Senate colleagues, George Hoar was not a strong advocate for an American intervention into Cuba in the late 1890s. On Decemebr 1897, he met with Native Hawaiian leaders opposed to the annexation their of nation and presented the Kūʻē Petitions to Congress which defeated William McKinley’s attempt to annex the Republic of Hawaii with a treaty. After this, the islands were annexed by means of joint resolution, called the Newlands Resolution. After the Spanish–American War, Hoar became one of the Senate’s most outspoken opponents of the imperialism of the McKinley administration. George Hoar pushed for and served on the Lodge Committee investigating alleged, and later confirmed, war crimes in the Philippine–American War. He also denounced the U.S. intervention in Panama. In addition to his political career, Hoar was active in the American Historical Association and the American Antiquarian Society, serving terms as president of both organizations. He was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1853, and served as vice-president from 1878 to 1884, and then served as president from 1884 to 1887. He was a regent of the Smithsonian Institution in 1880, and a trustee of the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. Through his efforts, the lost manuscript of William Bradford’s Of Plymouth Plantation (1620–47), an important founding document of the United States, was returned to New England, after being discovered in Fulham Palace, London, in 1855. George Hoar was elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1901. His autobiography, Autobiography of Seventy Years, was published in 1903; it first appeared in serial form in Scribner’s magazine. Hoar enjoyed good health until June 1904. He died in Worcester, and was buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord. After his death, a statue of him was erected in front of Worcester’s city hall, paid for by public donations.

Born

- August, 29, 1826

- USA

- Concord, Massachusetts

Died

- September, 30, 1904

- USA

- Worcester, Massachusetts

Cemetery

- Sleepy Hollow Cemetery

- Concord, Massachusetts

- USA