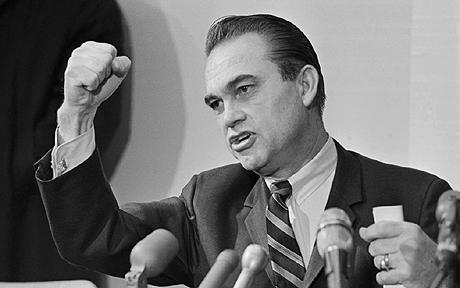

George Wallace (George Corley Wallace)

George Wallace

George C. Wallace, 79, the four-time governor of Alabama and four-time candidate for president of the United States who became known as the embodiment of resistance to the civil rights movement of the 1960s, died last night in Montgomery, Ala. He had battled Parkinson’s disease in recent years.

Cut down by a would-be assassin’s bullet in Laurel in 1972 while campaigning in Maryland’s Democratic presidential primary, he spent the rest of his life in a wheelchair, paralyzed from the waist down. He was in and out of hospitals for treatment of his paralysis and the constant pain caused by the bullet that had injured his spinal cord.

Wallace entered Jackson Hospital on Thursday, suffering from breathing problems and septic shock caused by a severe bacterial infection. He also had been hospitalized this summer with similar problems. Wallace’s son, George Wallace Jr., and one of his daughters, Peggy Wallace Kennedy, were at his side when he died.

Wallace was elected governor the first time in 1962, with what was the largest popular vote in state history and with the declaration: “I draw the line in the dust and toss the gauntlet before the feet of tyranny, and I say, segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever.”

For the next 15 years he made a political career, usually on the national stage, as a man who opposed the advancement of rights for blacks, as well as the powers of the federal government. After notable clashes with Washington over school integration in Alabama, he took his campaign to the nation.

In 1964, Wallace was a candidate in several Democratic primaries, scoring what were then surprisingly large vote totals in such states as Maryland and Wisconsin. In 1968, he ran for president on his own American Independent Party ticket, winning nearly 10 million votes, about 13 percent of the total, in a campaign in which he vilified blacks, students and people who called for an end to the war in Vietnam. He carried five Southern states and won 46 electoral votes

In 1972, he returned to the Democratic Party fold and was a formidable candidate in that year’s presidential primaries. As the most forceful national opponent of “forced busing” for school integration, he galvanized supporters who had never supported him before. But his campaign effectively ended in Laurel, when he was struck down by bullets from a gun fired by Arthur Bremer.

Nevertheless, he won primaries in North Carolina, Michigan, Maryland, Florida, Tennessee and Florida. He no longer could be dismissed as a mere regional candidate.

Wallace returned to the presidential trail, for the last time, in 1976. A near-wraith, his roar of defiance was diminished by both physical limitations and time. National racial tension was, arguably, lessening and Vietnam was no longer a burning issue. His battle cry to the voters of “send them a message!” fell on increasingly unreceptive ears.

Wallace ended up endorsing former Georgia governor Jimmy Carter, who went on to defeat Republican Gerald R. Ford for the presidency in 1976.

If Wallace’s presidential campaigns all ended in defeat, few really thought he had any serious chance. On the other hand, he strode the Alabama political stage like a colossus for over a quarter-of-a-century.

Forbidden to run by law for re-election as governor in 1966, he saw his first wife, Lurleen, elected governor in his stead. She died in office, of cancer, two years later. In 1970, he defeated her successor and won a second four-year term as governor. In 1974, with state law changed, he was elected governor a third time. He stepped down in 1979.

In 1982, he ran for governor a fourth time. In a watershed moment, he admitted that he had been wrong about “race” all along. He was elected by a coalition represented by blacks, organized labor and forces seeking to advance public education. In that race, he carried all 10 of the state’s counties with a majority black population, nine of them by a better than two-to-one margin. He retired four years later, an increasingly remote and physically tormented man.

“We thought [segregation] was in the best interests of all concerned. We were mistaken,” he told a black group in 1982. “The Old South is gone,” but “the New South is still opposed to government regulation of our lives.”

Wallace came to national prominence in 1963 when he kept a campaign pledge to stand “in the schoolhouse door” to block integration of Alabama public schools. On June 11, 1963, he personally barred the path of two black students attempting to register at the University of Alabama. The governor was flanked by armed state troopers. He defied federal Justice Department orders to admit the students, James A. Hood and Vivian J. Malone.

President Kennedy federalized the Alabama National Guard and ordered some of its units to the university campus. Wallace stood aside and the black students were allowed to register for classes.

In September 1963, Wallace ordered state police to Huntsville, Mobile, Tuskegee and Birmingham to prevent public schools from opening, following a federal court order to integrate Alabama schools. Helmeted and heavily armed state police and state National Guard units kept students and faculty from entering schools. Following civil disturbances resulting in at least one death, President Kennedy again nationalized the Guard and saw the schools integrated.

On March 7, 1965, state troopers with dogs, whips and tear gas tangled blacks during a voter registration campaign who were marching from Selma to Montgomery. The violence, which an entire nation witnessed on television, helped mobilize enough support to enable President Johnson to win passage of the landmark 1965 Voting Rights Act.

In 1964, Wallace campaigned as a Democratic candidate for president and attempted to explain himself outside the south. He said he opposed the growing powers of the federal government, especially the courts and the bureaucracy, which he held up to ridicule. He pointed out that federal judges and bureaucrats had been elected by no one and were increasingly usurping powers of the individuals and states. He portrayed them as underworked self-important “pointy-headed” intellectuals who had their heads in the clouds and their lunches in their trademark attache cases.

By 1968, Wallace was a true national figure who had become the leading spokesman of forces opposed to civil rights. As a third party candidate, he opposed Republican Richard M. Nixon and Democrat Hubert H. Humphrey in the general election, maintaining that there was not a “dime’s worth of difference” between the two.

George Corley Wallace was born Aug. 25, 1919 in Clio, Ala. He grew up working on the family farm.

In 1958, after serving in World War II, as assistant state attorney general in Alabama and two terms in the state legislature, Wallace ran his first race for governor and was defeated by John Patterson in the Democratic primary by a vote of 314,000 to 250,000. He later attributed this to being “out-segged” by his opponent. He vowed that in any future contest, that he would be the loudest and most impassioned voice calling for racial segregation.

He won the governorship in 1962. According to a Saturday Evening Post story, he “campaigned like a one-man army at war with the Federal government.” If he did not abandon his populist calls for helping the poor through education and health care, those calls became a distant second to his harping on the racial issue.

The sad fact is that from first to last, despite the sound and the fury of Wallace’s campaigning, little changed for the good in Alabama with his help. Throughout all his years in office, Alabama rated near the bottom of the states in per capita income, welfare, and spending on schools and pupils.

Born

- August, 25, 1919

- Clio, Alabama

Died

- September, 13, 1998

- Montgomery, Alabama

Cause of Death

- septic shock from a bacterial infection

Cemetery

- Greenwood Cemetery

- Montgomery, Alabama