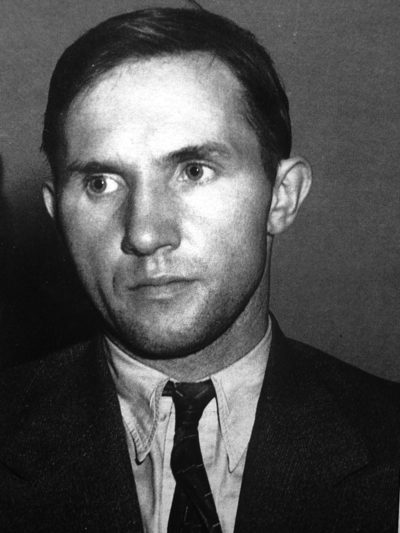

Bruno Hauptmann (Bruno Hauptmann)

Bruno Hauptmann was born Bruno Richard Hauptmann in Kamenz, near Dresden in what was then the German Empire, the youngest of five children. Neither he nor his family and friends used the name “Bruno,” although prosecutors in the Lindbergh kidnapping trial referred to him by that name. He had three brothers and a sister. At age 11, he joined the Boy Scouts (Pfadfinderbund). Bruno Hauptmann attended public school (Realschule), but quit at the age of 14. He then worked during the day while attending trade school (Gewerbeschule) at night, studying carpentry for the first year, then switching to machine building (Maschinenschlosser) for the next two years. In 1917, Hauptmann’s father died. The same year, Hauptmann learned his brother Herman had been killed fighting in France in World War I. Not long after that, he was informed that his brother Max was now dead too, having fallen in Russia. Shortly thereafter, Hauptmann was conscripted and assigned to the artillery. Upon receiving his orders, he was sent to Bautzen, but was transferred to the 103rd Infantry Replacement Regiment upon his arrival. In 1918, Hauptmann was assigned to the 12th Machine Gun Company at Königsbrück. Hauptmann would claim that he was deployed to Western France with the 177th Regiment of Machine Gunners in either August or September 1918 then fought in the Battle of Saint-Mihiel. Bruno Hauptmann would also say he was gassed in either September or October 1918. He also claimed that while his position was being shelled, he was hit in the helmet with a piece of metal. According to him, this knocked him out for hours, and he was left for dead. When he came to, he crawled back to safety and was back to the machine guns that evening. After the war, Hauptmann and a friend robbed two women wheeling baby carriages they were using to transport food on the road between Wiesa and Nebelschütz. The friend wielded Hauptmann’s army pistol during the commission of this crime. Hauptmann’s other charges include burgling a mayor’s house (using a ladder). Released after three years in prison, he was arrested three months later on suspicion of further burglaries. Hauptmann illegally entered the US by stowing away on a liner. Landing in New York in September 1923, the 24-year-old Hauptmann was taken in by a member of the established German community and worked as a carpenter. He married a German waitress in 1925 and became a father eight years later.

Bruno Hauptmann was slim and of medium height, but broad shouldered. His eyes were described as being small and deep-set. The kidnapping of Charles Lindbergh Jr. occurred on the evening of March 1, 1932. A man was believed to have climbed up a ladder placed under the bedroom window of the child’s room and quietly snatched the infant by wrapping him in a blanket. A note demanding a ransom of $50,000 was left on the radiator that formed a windowsill for the room. The ransom was delivered, but the infant was not returned. A corpse identified as the boy’s was found on May 12, 1932, in the woods 4 miles (6.4 km) from the Lindbergh home. The cause of death was listed as a blow to the head. It has never been determined whether the head injury was accidental or deliberate; some have theorized that the fatal injury occurred accidentally during the abduction. During the opening to the jury in the trial, New Jersey Attorney General David Wilentz claimed the child died by a fall from the ladder. However during the state’s summation, Wilentz would claim the child was killed in the nursery after having been hit in the head with the chisel found at the scene. This material variance in theory as to both the location and cause of death by the state was one of the major points included in Hauptmann’s appeal process. More than two years after the abduction, authorities finally discovered a promising lead in the form of recent ransom notes which appeared to be the work of the very same individual. Soon this information was leaked to the press, which sought verification that the police were closing in on the kidnapper or kidnappers.

Then, on September 15, 1934, a $10 gold certificate that was part of the ransom was given to a gas station attendant as payment. Gold certificates were rapidly being withdrawn from circulation; to see one was unusual and, in this case, attracted attention. The attendant wrote down the license plate number of the car and gave it to the police. The New York license plate belonged to a dark blue Dodge sedan owned by Hauptmann. After successfully tracing the plate to Bruno Hauptmann, he was placed under surveillance by a team consisting of members of the New York City Police Department, New Jersey State Police, and the FBI. On the morning of September 19, 1934, the team followed Hauptmann as he left his apartment on Needham Avenue and East 222nd Street in the Bronx, but were quickly noticed. As a result, Hauptmann attempted to get away by ignoring red lights and traveling at high speed. As the chase continued, Hauptmann was accidentally boxed in by a municipal sprinkler truck between 178th Street and East Tremont Avenue. Hauptmann was placed in handcuffs.

On April 3, 1936, Bruno Hauptmann was executed in “Old Smokey”, the electric chair at the New Jersey State Prison. Hauptmann’s last meal consisted of coffee, milk, celery, olives, salmon salad, corn fritters, sliced cheese, fruit salad, and cake. Reporters present at the execution reported that he went to the electric chair without saying a word. He had addressed his last words to his spiritual advisor, Rev. James Matthiesen, minutes prior to being taken from his cell to the death chamber. He reportedly said, “Ich bin absolut unschuldig an den Verbrechen, die man mir zur Last legt”, which Matthiesen told Gov. Hoffman meant “I am absolutely innocent of the crime with which I am burdened.” After the execution, Hauptmann’s widow applied for and received the special permission that was required to take her husband’s body out of state so that it could be cremated at the U.S. crematory (also called the Fresh Pond Crematory) in the Maspeth neighborhood of Queens, New York. The memorial service there was religious (two Lutheran pastors conducted the service in German) and private (under New Jersey law, public services were not permitted for felons, and Anna Hauptmann had agreed to this as a condition of receiving her husband’s body) and was attended by only six people (the legal limit under New Jersey rules), but a crowd of over 2,000 gathered outside. Hauptmann’s widow had planned to return to Germany with the ashes. Anna Hauptmann died in 1994 at age 95.

Born

- November, 26, 1899

- Germany

- Kamenz, Saxony

Died

- April, 03, 1936

- USA

- Trenton, New Jersey

Cause of Death

- electric chair

Other

- Cremated