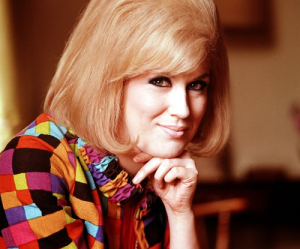

Dusty Springfield (Mary Isobel Catherine Bernadette O'Brien)

Dusty Springfield

Call me a crazy old physiognomist, but my theory is that you can always spot a lesbian by her big thrusting chin. Celebrity Eskimo Sandi Toksvig, Ellen DeGeneres, Jodie Foster, Clare Balding, Vita Sackville-West, God love them: there’s a touch of Desperate Dan in the jaw-bone area, no doubt the better to go bobbing for apples.

It is thus a tragedy that Dusty Springfield’s whole existence was blighted by her orientation, which explains ‘the silence and secrecy she extended over much of her life, and her self-loathing’. One glance at her chin should have revealed all — but the Sixties was not a fraction as liberated and swinging as people now assume. ‘Being gay was either a pitiable affliction or an actual mental illness,’ Karen Bartlett reminds us in this sympathetic biography. Victims were treated with aversion therapy and electric shocks.

Male homosexuality is frequently discussed (John Sparrow believed that ‘all the fun went out of it’ when it became legal), but generally we hear a lot less about the plight of lesbians, who ‘faced utter rejection by a society that emphasised femininity at all costs. Women must marry, and marry young, to avoid a life on the shelf.’

The agony created by such social stipulations was widespread and intense. I myself can recall heaps of furious married dragon-women in Wales, who wore wrinkle-resistant Crimplene trousers and sublimated their feelings working with horses or running Girl Guide camps. The chapel coerced behaviour — as did Catholicism. Dusty Springfield was born as Mary Isobel Catherine Bernadette O’Brien in 1939, the ‘dumpy red-headed’ daughter of Irish immigrants in Ealing. Even as late as 1973 she was telling her (female) partner, ‘If I walk into that church the ceiling is going to fall on me. I’m going to be dead because I’m such a sinner.’

Mary/Dusty was educated at a convent school. Her father was ‘overweight, bespectacled and balding,’ a tax adviser who refused to sit the accountancy exams because ‘he really wanted to be a concert pianist’. He also never did any gardening, as ‘there could be snakes hiding in the undergrowth’. Meantime, Dusty’s mother was continuously drunk and sat all day in cinemas.

It was a domestic atmosphere of ‘terrible tension and fuming rows’. occasionally enlivened with food fights at the dinner table. Dusty’s father called her ‘stupid and ugly’, so she scalded herself and self-harmed to prove she was alive and not thoroughly numb. ‘The feelings of inadequacy followed me through my life,’ she later admitted— and her solace was to listen to (and emulate) Carmen Miranda, Doris Day and Billie Holiday, who turned pain and a tortured personal history into art.

The nuns wanted Mary O’Brien to be a librarian — i.e. they’d perceived she was more likely to be a mousey spinster than a fecund mother. But the future Dusty was determined to rebel. She bleached her hair and turned herself into someone else. ‘I just suddenly decided, in one afternoon, to be this other person who was going to make it.’

Were this a musical on the West End or Broadway stage, this would mark the climax of Act One. Dusty immersed herself in jazz and the blues and made her debut in Clacton-on-Sea, teaming up with another musician who’d ‘once taught Elizabeth Taylor’s children to water-ski’. Calling herself ‘a calculating bastard’, Dusty merged rock-and-roll with ‘a folksy formula’, and wearing ornate dresses with stiff petticoats, belted out ballads in a style reminiscent of Cilla, Lulu, Sandie Shaw, Kiki Dee and Petula Clark combined.

Dusty toured Butlin’s holiday camps in a VW camper, staying in digs with three-bar electric fires and a shared lavatory. She was a hostess in nightclubs frequented by the Krays and Christine Keeler. She appeared in cabarets with magicians, second-rate Spanish dancers ‘and a female fire-eater’. Her first television show was with Benny Hill. Bartlett doesn’t quite explain how it happened, but by 1963 Dusty was earning today’s equivalent of £25,000 a week.

The following year, the singer undertook a 29-date UK tour, followed by Australia and New Zealand. She was deported from South Africa, however, for ‘flatly refusing’ to perform before segregated audiences. Brutish apartheid reminded her of the prejudice and ignorance shown to homosexuals. To their eternal shame, Max Bygraves and Derek Nimmo publicly criticised Dusty for her stand, complaining that she’d now ‘made it difficult’ for British entertainers to go to the Cape and make big money. But racism was by no means confined to South Africa. At home and in America, Little Richard and Ray Charles never had their faces prominently shown on album covers.

Though Dusty spent much time in the States, ‘shooting in the woods’ in the South and encountering the bass-player who’d ‘taught Elvis how to do karate,’ she started to unravel at the very moment she won her greatest success. By 1966, ‘she had achieved more hit records than any other artist’. She had a nose job at the London Clinic. She was ‘constantly striving for perfection’, and was always late because it took three hours to apply her make-up. Dusty ‘often stretched the music business of the Sixties to their limits’ — but she also stretched the limits of sanity in her personal misbehaviour.

Dusty would send out for boxes of crockery, which she would then systematically smash against a wall. ‘That’s when I realised how weird it all was,’ says her lover, Sue Cameron. She tipped bags of flour over the band, punch bowls over her own head. Her pranks were not funny — they were mad. She festooned a house with lavatory paper, flung food in restaurants, and threw all her furniture into the swimming pool. She had a fight with Buddy Rich and knocked off his wig. (‘You fucking broad, who do you think you fucking are, bitch ?’). Dusty ended up in a secure ward at Bellevue Psychiatric Hospital, New York, suffering from a ‘catatonic nervous breakdown’.

The pills and vodka didn’t help. Dusty began drinking to give herself courage to have ‘sexual experiences’ with a woman, and as a ‘bachelor girl’, the very phrase used by interviewers, making her own way, she had no one to fall back on. No partner or family. Pitifully, ‘she wanted to feel safe — and never did.’ Sacked from The Talk of the Town, she was replaced by Bruce Forsyth. Asked to record a theme-song for a Bond movie, she couldn’t ‘get it together’ and Carly Simon was hired instead. By 1985, Dusty was reduced to earning $500 a night miming to her old hits in West Hollywood gay bars. ‘Battered and bruised’, and with her front teeth knocked out in a lesbian skirmish, she was admitted to hospital yet again.

Act Two, therefore, charts a pitiful and lonely decline. Dusty ‘wanted to be straight and she wanted to be a good Catholic and she wanted to be black’, sums up Norma Tanega, one of her partners. But Dusty operated at a time when ‘being gay was career poison’, so instead she went to pieces. The industry was so ‘homophobic and sexist, being a lesbian was considered awful and shocking’. Nor did newspapers want to know. ‘In those days girls in her situation didn’t come out and talk about being gay or bisexual.’ If actresses, they played tweedy old maids or sour housekeepers, like Agnes Moorehead. Or perhaps they became dog breeders or managed a garden centre. Maybe they became nuns. If you were Noele Gordon, you ran the gamut.

So: ‘she would scream a lot. She would also threaten to harm herself.’ When Dusty ran along the street, smashing car windows, Billie Jean King ‘arrived to calm things down’. Instead of suicide, Dusty got breast cancer. She moved to Taplow in Buckinghamshire, where she would eat only cauliflower and ice cream. Her household rubbish had to be cut up into pieces of identical size. She’d spend all day watching Bonanza in German on satellite television. She died in 1999. An operatic tale indeed — but did Dusty really have an affair in Mustique with Princess Margaret? If I am sceptical it is only because Hanoverians have small chins.

Born

- April, 16, 1939

- West Hampstead, England

Died

- March, 02, 1999

- Oxfordshire, England

Cause of Death

- Breast cancer

Cemetery

- St. Mary the Virgin, Churchyard

- Oxfordshire, England