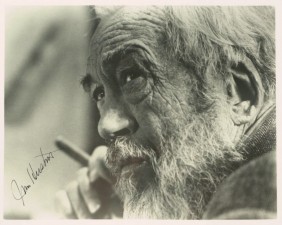

John Huston (John Marcellus Huston)

John Huston

John Huston, the legendary director and scenarist who made such classic films as ”The Maltese Falcon,” ”The Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” ”The Asphalt Jungle” and ”The African Queen,” died yesterday in Middletown, R.I., at the age of 81. Associates said he had died in his sleep of complications from emphysema.

The film maker, who lived as hard and at times as dangerously as the protagonists of his movies, rarely slowed his pace. Though he had suffered for decades from acute emphysema, which forced him in recent years to rely on oxygen tanks to help him breathe, he continued to smoke.

Mr. Huston was in Rhode Island for the filming of ”Mister North,” a movie based on Thornton Wilder’s novel ”Theophilus North,” which he was producing and had written with Janet Roach. Mr. Huston was admitted to Charleton Memorial Hospital in nearby Falls River, Mass., July 28 for treatment of pneumonia. He celebrated his 81st birthday there on Aug. 5, and was released last week.

Mr. Huston died at 2 A.M. in a house he had rented for the duration of the filming, a family spokesman said.

Early this summer he completed his last directorial work, making ”The Dead” – as yet unreleased – from a James Joyce story. Mr. Huston’s debilitating illness made him uninsurable, so the producers, who included his son Tony, had to insure another director willing to take over if necessary.

Among the film maker’s distinctive achievements was casting his father, Walter, in ”The Treasure of the Sierra Madre” in 1948 and his daughter Anjelica in ”Prizzi’s Honor” 37 years later, in roles for which each won an Academy Award.

Mr. Huston directed 41 films over 46 years and co-adapted and acted in more than 20. He was a flamboyant raconteur, bon vivant, horseman, big-game hunter and eventually filmdom’s grand old maverick.

At a 1983 testimonial, Lauren Bacall, a longtime friend, described him as ”daring, unpredictable, maddening, mystifying and probably the most charming man on earth.”

The best Huston films have lean, fast-paced scripts and vibrant plots and characterizations, and many of them deal ironically with vanity, avarice and unfulfilled quests. In them, nonconformists and misfits brave danger fatalistically in a world where women are often peripheral.

He directed most of Hollywood’s stars with a sportive irreverence toward their images, and bucked Hollywood’s penchant for happy endings by concluding an unusual number of movies with love unsatisfied.

Mr. Huston sought repeatedly to transpose the interior essence of literature to film with dramatic and visual tension, and he had the boldness to film such novels as Stephen Crane’s ”Red Badge of Courage” (1951); Herman Melville’s ”Moby Dick,” for which he won the New York Film Critics’ best-director award for 1956; Flannery O’Connor’s ”Wise Blood” (1979) and Malcolm Lowry’s ”Under the Volcano” (1984). The film maker took uncommon care to preserve the writers’ styles and values.

Debut With ‘Maltese Falcon’

Mr. Huston made a dazzling directorial debut with ”The Maltese Falcon,” which he adapted from the novel by Dashiell Hammett. The compelling 1941 movie is considered by many critics to be the best detective thriller ever filmed.

”The Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” a superb study of greed, gold and self-preservation adapted from a novel by B. Traven, gained for Mr. Huston the best-writer and best-director Academy Awards for 1948. ”The Asphalt Jungle” (1950) is a superbly incisive tale of crime and corruption. ”The African Queen,” a rollicking adventure movie based on a novel by C. S. Forester about a hard-drinking river trader (Humphrey Bogart) and a prim missionary (Katharine Hepburn), won Mr. Bogart a 1951 Oscar.

Detractors at times accused Mr. Huston of shallowness and of lacking conviction and commitment, though they acknowledged that even his inferior films had interesting elements. Critics seemed confounded by the lack of a common, unifying theme. In rebuttal, Mr. Huston called his film making eclectic, explaining, ”I don’t seek to interpret reality by placing my stamp on it. I never try to duplicate myself. One must avoid personal cliches.”

In the 1960’s, his reputation was clouded by a number of movies that critics denounced as muddled and at times sloppy claptrap, and many reviewers began to underrate even his better efforts.

But in the 1970’s and 80’s, despite emphysema and heart disease, he filmed such works as ”Fat City” (1972), about the gritty world of small-time boxers; ”The Man Who Would Be King” (1975), based on a Rudyard Kipling story about two British sergeants who seek, find and lose a great treasure in a remote land; ”Wise Blood,” an exuberant, haunting 1979 movie about religious guilt and obsession; ”Under the Volcano,” a drama of a doomed alcoholic (with a tour de force performance by Albert Finney), and ”Prizzi’s Honor,” a black comedy about the Mafia in Brooklyn and lovers who turn out to be killers for hire. The New York Film Critics Circle voted ”Prizzi’s Honor” the best movie of 1985.

Concern Over New Directors

Mr. Huston voiced concern that the large new generation of directors emerging from film schools was ”in terrible danger of cannibalism.” Elaborating, he said, ”If you make movies about movies and about characters instead of people, the echoes get thinner and thinner until they’re reduced to mechanical sounds.”

As his 80th birthday approached, he was honored with a series of career-achievement awards from many leading organizations, including the American Film Institute, the Film Society of Lincoln Center and the juries at the Cannes and Venice film festivals.

In 1985, Vincent Canby, the film critic of The New York Times, lauded Mr. Huston for ”the amazing endurance of his first-rate cinematic intelligence, the variety of his films and the consistency with which he has recouped his fortunes with a good film after turning out some bad ones.”

”It may now be time to call him a master,” Mr. Canby said.

A 6-foot-2, lanky man with a craggy, kindly face, Mr. Huston said he learned to act by studying his father’s performances. In a score of roles, the son had a benign self-assurance, playing the tough but compassionate title character in ”The Cardinal” (1963), Noah and the voice of God in his own ”Bible” (1966), the venal father of Faye Dunaway in ”Chinatown” (1974) and a charismatic tycoon in ”Winter Kills” (1979).

Vaudeville and Race Tracks

John Huston was born on Aug. 5, 1906, in Nevada, Mo., the only child of Walter Huston and the former Reah Gore, a journalist. After their divorce, when he was 6, he often traveled with each separately – on vaudeville tours with his father and to race tracks with his mother, who worked as a sports reporter.

He gave differing accounts of his childhood, perhaps because the years were unhappy. He was sickly and, at 12, was treated for an enlarged heart and a kidney ailment. However, he soon recovered and learned to box at Lincoln Heights High School in Los Angeles. At 15, he dropped out of school to be a boxer, becoming a top-ranking amateur lightweight in California, with a broken nose to show for it.

Though his formal education had ended, the young Mr. Huston continued to read voraciously. He took painting lessons in Los Angeles and in New York, where, at 19, he acted in several Off-Broadway plays.

Mr. Huston then spent two years in Mexico, where an Army officer gave him riding lessons. When he could no longer pay for them, the officer gave him an honorary commission in the Mexican cavalry so he could get the lessons free. Back in New York, he wrote a short story for H. L. Mencken’s American Mercury and did reporting for The Daily Graphic, where his mother also worked. His articles sometimes contained glaring factual errors, and he was soon dismissed.

Wrote for Early Talkies

His father then helped him get writing contracts for early talkies in Hollywood, and his first script credits were for two films starring the elder Huston – ”A House Divided” (1931) and ”Law and Order” (1932) – and for ”Murders in the Rue Morgue” (1932).

The writer quickly gained a Hollywood reputation as a lusty, hard-drinking libertine. In an autobiography, ”An Open Book” (1980), he recalled his life at the time as a ”series of misadventures and disappointments,” culminating in a 1933 accident in which a car he was driving struck and killed a young woman. A coroner’s jury absolved him of blame, but, traumatized, he left Hollywood and spent almost a year living a drifter’s life in London and Paris. Back home, he got occasional writing, editing and acting jobs in New York and Chicago.

In late 1937 at 31, nearly five years after the auto accident, he returned to Hollywood to become a serious writer at Warner Brothers, determined to direct his scripts. Over the next four years, he co-wrote the scripts for such hits as ”Jezebel,” ”The Amazing Dr. Clitterhouse,” ”Juarez,” ”Dr. Ehrlich’s Magic Bullet,” ”High Sierra” and ”Sergeant York.”

Mr. Huston won a director’s contract in 1941 and filmed ”The Maltese Falcon,” starring Humphrey Bogart, Mary Astor, Sidney Greenstreet and Peter Lorre. The movie, made in eight weeks for $300,000, was an immediate artistic and commercial success that continues to win new fans four decades later. In 1942, he directed two more hits, ”In This Our Life,” starring Bette Davis, and ”Across the Pacific,” another Humphrey Bogart thriller. He then joined the Army Signal Corps as a captain.

Three Wartime Films

While in uniform, he directed and produced three films that critics rank among the finest made about World War II: ”Report from the Aleutians” (1943), about bored soldiers preparing for combat; ”The Battle of San Pietro” (1944), a searing (and censored) story of an American intelligence failure that resulted in the deaths of many soldiers, and ”Let There Be Light” (1945).

The last, about psychologically damaged combat veterans, was suppressed for 35 years for being too antiwar. It had its first public showing in 1981 and won critical approval.

Mr. Huston rose to the rank of major and received the Legion of Merit for courageous work under battle conditions.

After the war, Huston movies included ”Key Largo” (1948), for which Claire Trevor won a supporting-actress Oscar; ”Beat the Devil” (1953), a wildly roguish comedy classic; ”Heaven Knows, Mr. Allison,” a 1957 war story; ”The Misfits” (1961), an introspective melodrama that was the last film made by Marilyn Monroe and Clark Gable; ”Freud” (1963); ”The Night of the Iguana” (1964); ”The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean” (1972) and ”Annie” (1982), a lavish, rambling production of the Broadway musical.

In making movies, Mr. Huston favored sequential shooting on location. He shot economically, eschewing the many protective shots favored by timid directors, and edited cerebrally so that financial backers would have trouble trying to cut scenes. He made brilliantly evocative use of color, particularly in ”Moulin Rouge” (1953) and ”Reflections in a Golden Eye” (1967), closely supervising all stages of production and invariably working under budget. He shot a picture intensely six days a week and, on Sundays, played equally intense poker with the cast and crew.

He was a thoughtful, patient craftsman who drew the best work from performers And crews. ”When I cast a picture,” he said, ”I do most of my directing in finding the right person. It’s a practice of mine to get as much out of the actor as I can, rather than to impose myself upon his performance.” He said he never tried to demolish an actor’s ego.

Mr. Huston’s consideration for performers was recounted by Lillian Ross in a 1952 series of New Yorker articles that detailed his making of the Civil War movie ”The Red Badge of Courage.” In his final instruction to actors before a downhill marching scene, he ordered: ”If anybody slips, he must be sure to protect the men in front from his bayonet.”

Disturbed by Blacklisting

Politically, Mr. Huston called himself a Jeffersonian Democrat. In the postwar years, he was increasingly disturbed by the Government’s frantic search for Communists and by the industry blacklisting that destroyed many careers.

Citing ”moral rot” at home, he moved to Galway, Ireland, in 1952 and made that his home until 1975, when he moved to Las Caletas, a remote hideaway on the west coast of Mexico. There, when not making movies, he spent his time reading, painting, snorkeling, caring for animals, and whale-spotting with ”my back to the jungle and my face to the sea.”

A reporter who interviewed him there in 1985 wrote that, despite serious illnesses, he was ”still a vigorous, unvanquished man.” Looking back, he said he missed the major studio era when people savored making movies, not just money.

Mr. Huston was married five times; his wives included the actress Evelyn Keyes and Enrica Soma, a ballet dancer. He was divorced from all his wives except Miss Soma, who was killed in an auto crash in 1969 after a 10-year marital separation.

Speaking of his wives last month, Mr. Huston told an interviewer, ”They were a mixed bag: a schoolgirl, a gentlewoman, a motion picture actress, a ballerina and a crocodile.”

Born

- August, 05, 1906

- Nevada, Missouri

Died

- August, 28, 1987

- Middletown, Rhode Island

Cause of Death

- pneumonia as a complication of lung disease

Cemetery

- Hollywood Forever Cemetery

- Hollywood,California