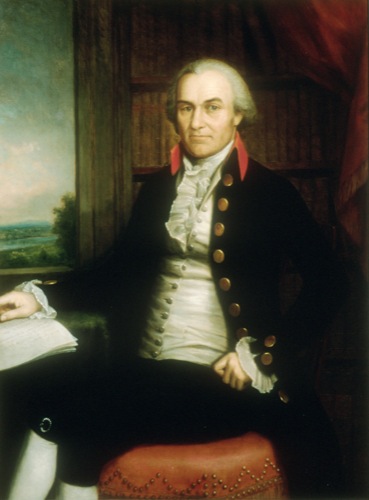

Oliver Ellsworth (Oliver Ellsworth)

Ellsworth was born in Windsor, Connecticut, to Capt. David and Jemima (née Leavitt) Ellsworth. He entered Yale in 1762, but transferred to the College of New Jersey (later Princeton) at the end of his second year. He continued to study theology and, while attending, helped found the American Whig–Cliosophic Society along with Aaron Burr and William Paterson. He received his A.B. degree, Phi Beta Kappa after 2 years. Soon afterward, however, Ellsworth turned to the law. After four years of study, he was admitted to the bar in 1771 and later became a successful lawyer and politician.

In 1772, Ellsworth married Abigail Wolcott, the daughter of Abigail Abbot and William Wolcott, nephew of Connecticut colonial governor Roger Wolcott, and granddaughter of Abiah Hawley and William Wolcott of East Windsor, Connecticut. They had nine children including the twins William Wolcott Ellsworth, who married Noah Webster’s daughter, served in Congress and became the governor of Connecticut; and Henry Leavitt Ellsworth, who became the first Commissioner of the United States Patent Office, the mayor of Hartford, president of Aetna Life Insurance and a large benefactor of Yale College. Oliver Ellsworth was the grandfather of Henry L. Ellsworth’s son Henry W. Ellsworth.

From a slow start Ellsworth built up a prosperous law practice. In 1777, he became Connecticut’s state attorney for Hartford County. That same year, he was chosen as one of Connecticut’s representatives in the Continental Congress. He served on various committees until 1783, including the Marine Committee, the Board of Treasury, and the Committee of Appeals. Ellsworth was also active in his state’s efforts during the Revolution, having served as a member of the Committee of the Pay Table that supervised Connecticut’s war expenditures. In 1777 he joined the Committee of Appeals, which can be described as a forerunner of the Federal Supreme Court. While serving on it, he participated in the Olmstead case that first brought state and federal authority into conflict. In 1779, he assumed greater duties as a member of the Council of Safety, which, with the governor, controlled all military measures for the state. His first judicial service was on the Supreme Court of Errors when it was established in 1785, but he soon shifted to the Connecticut Superior Court and spent four years on its bench.

On May 32, 1787, Ellsworth joined the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia as a delegate from Connecticut along with Roger Sherman and William Samuel Johnson. More than half of the 55 delegates were lawyers, eight of whom, including both Ellsworth and Sherman, had previous experience as judges conversant with legal discourse. Ellsworth in particular played an important role in having participated in the exclusion of judicial review from the Constitution at the Convention and later in having put it into force in the 1789 Judiciary Act.

Ellsworth took an active part in the proceedings beginning on June 20, when he proposed the use of the name the United States to identify the government under the authority of the Constitution. The words “United States” had already been used in the Declaration of Independence and Articles of Confederation as well as Thomas Paine’s The American Crisis. It was Ellsworth’s proposal to retain the earlier wording to sustain the emphasis on a federation rather than a single national entity. Three weeks earlier, on May 30, 1787, Edmund Randolph of Virginia had moved to create a “national government” consisting of a supreme legislative, an executive and a judiciary. Ellsworth accepted Randolph’s notion of a threefold division, but moved to strike the phrase “national government.” From this day forward the “United States” was the official title used in the Convention to designate the government, and this usage has remained in effect ever since. The complete name, “the United States of America,” had already been featured by Paine, and its inclusion in the Constitution was the work of Gouverneur Morris when he made the final editorial changes in the Constitution.

Ellsworth played a major role in the passage of the Connecticut Plan. During debate on the Great Compromise, often described as the Connecticut Compromise, he joined his fellow Connecticut delegate Roger Sherman in proposing the bicameral arrangement in which members of the Senate would be elected by state legislatures as indicated in Article I, Section 3 of the Constitution. Ellsworth’s version of the compromise was adopted by the Convention, but it was later revised by Amendment XVII substituting a popular vote similar to that used for the House of Representatives.

To gain the passage of the Connecticut Plan its proponents needed support of three southern states, Georgia and the two Carolinas, complementing the small state coalition of the North. It came as no surprise that Ellsworth favored the Three-Fifths Compromise on the enumeration of slaves and opposed the abolition of the foreign slave trade. Stressing that he had no slaves, Ellsworth spoke twice before the Convention, on August 21 and 22, in favor of slavery being abolished.

Along with James Wilson, John Rutledge, Edmund Randolph, and Nathaniel Gorham, Ellsworth served on the Committee of Detail which prepared the first draft of the Constitution based on resolutions already passed by the Convention. All Convention deliberations were interrupted from July 26 to August 6, 1787, while the Committee of Detail completed its task. The two preliminary drafts that survive as well as the text of the Constitution submitted to the Convention were in the handwriting of Wilson or Randolph. However, Ellsworth’s role is made clear by his 53 contributions to the Convention as a whole from August 6 to 23, when he left for business reasons. As James Madison tabulated in his Records, only Madison and Gouverneur Morris spoke more than Ellsworth during those sixteen days.

Though Ellsworth left the Convention near the end of August and didn’t sign the final document, he wrote the Letters of a Landholder to promote its ratification. He also played a dominant role in Connecticut’s 1788 ratification convention, when he emphasized that judicial review guaranteed federal sovereignty. It seems more than a coincidence that both he and Wilson served as members of the Committee of Detail without mentioning judicial review in the initial draft of the Constitution, but then stressed its central importance at their ratifying conventions just a year preceding its inclusion by Ellsworth in the Judiciary Act of 1789.

Along with William Samuel Johnson, Ellsworth served as one of Connecticut’s first two United States senators in the new federal government, and his service extended from 1789 to 1796. During this period he played a dominant role in Senate proceedings equivalent to that of Senate Majority Leaders in later decades. According to John Adams, he was “the firmest pillar of [Washington’s] whole administration in the Senate.”[Brown, 231] Aaron Burr complained that if Ellsworth had misspelled the name of the Deity with two D’s, “it would have taken the Senate three weeks to expunge the superfluous letter.” Senator William Maclay, a Republican Senator from Pennsylvania, offered a more hostile assessment: “He will absolutely say anything, nor can I believe he has a particle of principle in his composition,” and “I can in truth pronounce him one of the most candid men I ever knew possessing such abilities.” [Brown, 224-25] What seems to have bothered McClay the most was Ellsworth’s emphasis on private negotiations and tacit agreement rather than public debate. Significantly, there was no official record of Senate proceedings for the first five years of its existence, nor was there any provision to accommodate spectators. The arrangement was essentially the same as for the 1787 Convention, in contrast to the open sessions of the House of Representatives.

Ellsworth’s first project was the Judiciary Act, described as Senate Bill No. 1, which effectively supplemented Article III in the Constitution by establishing a hierarchical arrangement among state and federal courts. Years later Madison stated, “It may be taken for certain that the bill organizing the judicial department originated in his [Ellsworth’s] draft, and that it was not materially changed in its passage into law.”[Brown, 185] Ellsworth himself probably wrote Section 25, the most important component of the Judiciary Act. This gave the Federal Supreme Court the power to veto state supreme court decisions supportive of state laws in conflict with the U.S. Constitution. All state and local laws accepted by state supreme courts could be appealed to the federal Supreme Court, which was given the authority, if it chose, to deny them for being unconstitutional. State and local laws rejected by state supreme courts could not be appealed in this manner; only the laws accepted by these courts could be appealed. This seemingly modest specification provided the federal government with its only effective authority over state government at the time. In effect, judicial review supplanted Congressional Review, which Madison had unsuccessfully proposed four times at the Convention to guarantee federal sovereignty. Granting the federal government this much authority was apparently rejected because its potential misuse could later be used to reject the Constitution at State Ratifying Conventions. Upon the completion of these conventions the previous year, Ellsworth was in the position to render the sovereignty of the federal government defensible, but through judicial review instead of congressional review.

Once the Judiciary Act was adopted by the Senate, Ellsworth sponsored the Senate’s acceptance of the Bill of Rights promoted by Madison in the House of Representatives. Significantly, Madison sponsored the Judiciary Act in the House at the same time. Combined, the Judiciary Act and Bill of Rights gave the Constitution the “teeth” that had been missing in the Articles of Confederation. Judicial Review guaranteed the federal government’s sovereignty, whereas the Bill of Rights guaranteed the protection of states and citizens from the misuse of this sovereignty by the federal government. The Judiciary Act and Bill of Rights thus counterbalanced each other, each guaranteeing respite from the excesses of the other. However, with the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment in 1865, seventy-five years later, the Bill of Rights could be brought to bear at all levels of government as interpreted by the judiciary with final appeal to the Supreme Court. Needless to say, this had not been the original intention of either Madison or Ellsworth.

Ellsworth was the principal exponent in the Senate of Hamilton’s economic program, having served on at least four committees dealing with budgetary issues. `These issues included the passage of Hamilton’s plan for funding the national debt, the incorporation of the First Bank of the United States, and the bargain whereby state debts were assumed in return for locating the capital to the south (today the District of Columbia). Ellsworth’s other achievements included framing the measure that admitted North Carolina to the Union, devising the non-intercourse act that forced Rhode Island to join the union, and drawing up the bill to regulate the consular service. He also played a major role in convincing President Washington to send John Jay to England to negotiate the 1794 Jay Treaty that prevented warfare with England, settled debts between the two nations, and gave American settlers better access to the Midwest.

On March 3, 1796, Ellsworth was nominated by President George Washington to be Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, the seat having been vacated by John Jay. (Jay’s replacement, John Rutledge, had been rejected by the Senate the previous December, and Washington’s next nominee, William Cushing, had declined the office in February.) The following day, Ellsworth was unanimously confirmed by the United States Senate, and received his commission.

Ellsworth served until his resignation due to poor health on September 30, 1800, and his brief contribution was overshadowed by the accomplishments of his successor, John Marshall, who succeeded him in 1801. However, four cases the Ellsworth Court decided were of lasting importance in American jurisprudence. Hylton v. United States (1796) implicitly addressed the Supreme Court’s power of judicial review in upholding a federal carriage tax (although it would not be until John Marshall succeeded Ellsworth that the court addressed this issue head on); Hollingsworth v. Virginia (1798) affirmed that the President had no official role in amending the Constitution of the United States, and that a Presidential signature was therefore unnecessary for ratification of an amendment; Calder v. Bull (1798) held that the Constitution’s Ex post facto clause applied only to criminal, not civil, cases; and New York v. Connecticut was the first exercise by the court of its original jurisdiction in cases between two states.

Ellsworth’s chief legacy as Chief Justice, however, is his discouragement of the previous practice of seriatim opinion writing, in which each Justice wrote a separate opinion in the case and delivered that opinion from the bench. Ellsworth instead encouraged the consensus of the Court to be represented in a single written opinion, a practice which continues to the present day. Ellsworth was a candidate in the 1796 United States presidential election, receiving eleven votes in the electoral college, sharing with John Adams the distinction of gaining most votes in both New Hampshire and Rhode Island.

As United States Envoy Extraordinary to the Court of France, Ellsworth led a delegation there between 1799 and 1800 in order to settle differences with Napoleon’s government regarding restrictions on U.S. shipping that might otherwise have led to military conflict between the two nations. The agreement accepted by Ellsworth provoked indignation among Americans for being too generous to Napoleon. Moreover, Ellsworth came down with a severe illness resulting from his travel across the Atlantic (causing him to tender his resignation from the Supreme Court while still in Europe in 1800), and the Federalist party had fallen into disarray and was easily defeated by Republicans led by Jefferson. As a result, Ellsworth retired from national public life upon his return to America in early 1801. He was nevertheless able to serve again on the Connecticut Governor’s Council until he died in Windsor in 1807.

Although many erroneously believe that he is buried on the grounds of the Ellsworth Homestead in Windsor, Connecticut, his remains are in the cemetery behind the First Congregational Church of Windsor overlooking the Farmington River.

Born

- April, 29, 1745

- USA

- Windsor, Connecticut

Died

- November, 26, 1807

- USA

- Windsor, Connecticut

Cemetery

- Palisado Cemetery

- Palisado Cemetery

- USA